Migration and Mobility within the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS)

In the mid-1990s, six countries bordering the Mekong river in Southeast Asia entered a program of sub-regional cooperation to enhance economic growth and reduce poverty through the development of economic corridors between countries and amongst rural and urban centres. This boosted connectivity and resulted in a massive increase in mobility across six borders, providing access to labour to at least 3 to 5 million migrant workers, entirely changing the sub-region’s socio-economic dynamics. Thailand is the primary receiving country in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS), attracting 60% of all intra-GMS migrants, followed by Viet Nam and the Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang (Guangxi) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which receive migrants from Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and Myanmar (ADB 2013, vii). Several push and pull factors motivate migration within the subregion including the promise of prosperity, unequal social-economic structures, the rural-urban divide between and within countries, as well as the porosity of borders and weak enforcement facilitating irregular entry. As a result, a majority of labour migrants within the GMS work in low-skilled, low wage jobs as irregular workers.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines regular migration as migration that occurs through recognized and authorized channels. It is estimated that up to 30,000 people cross the borders between Thailand and it’s GMS counterparts in one leg on the busiest day, with a majority of them lacking proper documentation, to work in agriculture, construction, and fisheries. These sectors, amongst many others, are more likely to employ irregular migrants due to the difficulty of the work and wages being lower than what nationals would accept, but enough to attract migrants escaping the unequal socio-economic divide (ADB 2013, 9). With a lack of robust enforcement against the employment of irregular migrants, ground-crossing borders become more porous facilitating smuggling and trafficking of migrants, particularly of women. There has been an increase in the number of women migrating within the subregion over the years, significantly contributing to economic growth. However, women have faced a higher risk of abuse and exploitation than their male counterparts due to their lack of negotiating power, prevailing gender-based discrimination and poor literacy (ADB 2013, 24).

Migration and Health Vulnerabilities

Within the subregion, migrants are disproportionately vulnerable to health risks, regardless of their migration status (regular, irregular, smuggled, trafficked). Migration itself is a social determinant of health for migrants, since the conditions in which they travel, live, and work carry significant risks for their physical, mental, and social health and well-being. Lack of access to health care services, primarily due to their migration status, restrictive immigration and employment policies, low literacy and awareness significantly diminishes migrant’s ability to protect themselves (McMichael, Celia, 2017). Even when migrants do have access to health services, most choose to avoid them because of fear of deportation, xenophobic and discriminatory attitudes from healthcare staff, and linguistic, cultural and gender barriers. Unsafe and exploitative working conditions, crowded housing, inadequate social security arrangements beget violence, sexual exploitation, social exclusion, separation from family, and anti‐migrant sentiments, all contributing to physical, mental, sexual, and behavioural health deterioration. Therefore, reiterating that the conditions under which migrants are exposed to make them more vulnerable to illness, and not migrants themselves (IOM, 2015).

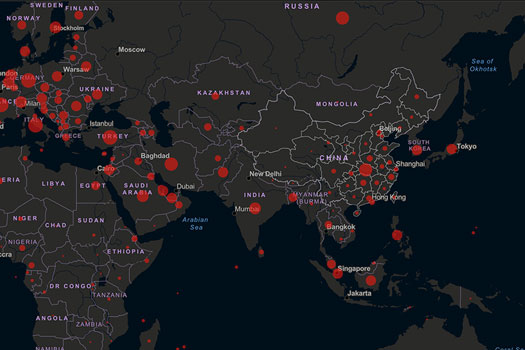

There is no clear systemic association between migration and the importation of communicable diseases, despite the common perception of it. Evidence suggests that communicable diseases are primarily connected with the extent of poverty (WHO n.d.). Most migrants start their long, exhausting journey with little to begin with, along the mobility continuum which constitute various travel routes, modes of transportation, and transit and congregation points along the way (IOM HBMM 2016, 4). Once they have reached their destinations, most find themselves living in poor conditions and socially marginalized, automatically carrying a significant risk for acquiring an infectious disease. In addition, in the time that transportation has connected globally, people (particularly short-term travellers such as business workers and tourists) move much faster around the world leading to the exponential spread and transmission of novel diseases, including introducing clusters into vulnerable and hard to reach migrant communities. This has been observed under the current ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Migration and the COVID-19 Pandemic

To date, COVID-19 has infected over 21 million people and taken the lives of more than 784,000 globally (as of 20 August, 2020). This crisis is having an unprecedented impact on the economy, healthcare, politics, as well as human rights by exacerbating pre-existing inequalities, particularly among the most vulnerable and marginalized people in numerous countries. The pandemic has established that diseases do not recognize borders and border measures alone will not prevent the spread of the disease. The outbreak had spread along busy commercial and touristic routes, which were already home to a large number of migrant workers, international students, asylum seekers and refugees. As the number of COVID-19 cases have increased across a growing number of countries within the Asia-Pacific region, receiving GMS countries have resorted to taking drastic measures by suspending international travel, closing borders, making changes to visa and/or entry requirements as well as imposing mandatory internal lockdowns, in the attempt to reduce the transmission of the SARS-COV-2 virus into their communities and give time for health systems to cope. However, a cascade of negative impacts in regard to mobility have followed endangering the lives of millions of people (IOM Policy Paper 2020, 1-2). These strict public health measures have paradoxically led to the initiation of rapid cross-border movements rather than halting them, with migrants (especially internal ones) leaving transmission hotspots out of fear of acquiring the infection and fleeing from the unanticipated effects of the lockdowns such as the loss of livelihood. Where the measures have halted movement, migrants have found themselves stranded and trapped with limited living, working, and repatriation options.

Situation on the Ground

Following the State of Emergency declared by the Royal Thai Government on 26 March 2020, the Government imposed curfews, a partial lockdown of its capital city and some provinces, and the closure of most air, sea and land borders to minimize the outbreak of COVID-19. On one hand, this resulted in the rapid movement of tens of thousands of migrant workers returning to their communities of origin via crowded buses. This increased the risk of seeding new clusters of COVID-19, which is particularly concerning in most home communities in the rural areas of Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar, where monitoring, testing or treating COVID-19 cases that may arise is extremely difficult. Therefore, border officials, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) and IOM, have been ensuring physical distancing, handwashing, the use of face masks and the provisioning of vital information materials on COVID-19 to the large volumes of people passing through in the hope of keeping the transmission rate down. While on the other hand, many migrants found themselves stranded in Thailand after being dismissed from employment with limited information and aid, affecting their access to immediate essential services (IOM Thailand COVID-19 Appeal 2020, 1-2).

Migrants waiting to cross border home at Maesot border June 2020. Photo Source: IOM

As transmission started to slow down over the passing months, Thailand began re-opening factories and businesses. However, with the cost of the 14-day mandatory quarantine upon entry to be borne by employers, many companies became discouraged to contract new or bring back migrant workers, paving the way for crossings and smuggling through unofficial Thai-Myanmar and Thai-Cambodia borders. The children of migrant workers who live in border communities were negatively affected as well with the closure of entry points and quarantine implementations, as many of them are enrolled in schools on the Thai side of the border and commuted across daily before the announcement. Similarly, prior to the closure, many people from Cambodia, Lao (PDR) and Myanmar travelled across the border seeking better health services. At present only patients with severe medical illnesses are permitted to make it across to referral hospitals following approval from the Provincial Governor, which can take longer than a week to process at some border crossing points.

Impacts of the Pandemic on Migrant Workers

Overall, migrants and mobile populations are facing three simultaneous crises at the moment. First, an unprecedented health crisis that has been worsened by their compromised access to essential health systems. There is also a lack of awareness on the availability of COVID-19 services. This can be attributed to low literacy rates, poor health-seeking behaviour, the absence of migrant’s inclusion in National Emergency Response Plans, as well as the fear of arrest, deportation, stigmatization and discrimination. These place the lives of migrants -and eventually host communities- in danger. Most migrants, irrespective of their legal status, are among some of the poorest living in crowded conditions where physical distancing is practically impossible with limited or no access to proper water and sanitation infrastructure (IOM Thailand COVID-19 Appeal 2020, 2). This overrides every risk communication efforts conducted for infection prevention mandated for protection against COVID-19. The rise in food insecurity and malnutrition is alarming as well, not due to food shortages, but rather due to the incessant restriction of movement, income, and remittance losses. Refugees, internally displaced populations (IDPs) and irregular workers living in temporary settlements, shelters and slums are hard to reach. Food and aid distribution now face more setbacks due to movement restrictions and physical distancing measures (The World Bank 2020).

Truck lines at Maesot border to bring goods to Myanmar June 2020. Photo Source: IOM

Second and thirdly, migrants are facing a protection and socio-economic crisis concurrently. Several countries have curtailed access to asylum for asylum seekers fleeing from war and persecution, and are detaining, deporting or forcing people to return back at borders. Although this is being endorsed in the name of infection prevention and control, it is instead adding to the xenophobic rhetoric of “foreigners” or “outsiders” as carriers of the virus, leading to assaults, social exclusion, diminished access to services, the boycotting of businesses, and discriminatory movement restrictions and quarantine policies. Even with the easing of strict lockdown measures, incidences of discrimination, xenophobia and anti-migrant sentiments have been increasingly surfacing due to the economic downturn (IOM Press release, 2020). The rise in unemployment, loss of livelihood, reduction or non-payment of wages is markedly affecting migrant workers, especially for low-skilled informal workers who are highly dependent on daily wages. The decline in remittances is expected to decrease further by almost US $110 billion worldwide by the end of 2020. The money sent back home is key for the survival of many households and communities, who will now have to depend on limited national welfare systems to make ends meet (ILO Policy Brief 2020, 2).

Women Migrants bear the brunt of COVID-19

Under present circumstances, women migrant workers are being hit the hardest on all fronts. Working in low-paid unstable jobs, as well as in essential sectors such as frontline nurses, cleaners and laundry workers, women are directly at a risk of exposure to the coronavirus. In addition to dealing with existing gender-based inequalities, restrictive migration policies and insecure forms of labour, women migrant workers are now faced with even fewer options upon retrenchment while also having to tend to the needs of their children and other dependents as a result of school closures and a return back home (UN Women 2020, 1). Furthermore, the levels of violence against women in accommodation, at work, in quarantine facilities or back home has been alarmingly heightened reversing substantial progress made on women’s labour and individual rights in the past decades. Much gender-based violence support services that most migrant workers rely upon have been downscaled to online and phone-only models or are closed since the announcement of lockdowns. Inevitably, this leaves them entirely unprotected and vulnerable.

Towards Solutions: Migrant Inclusion and Multi-Sectoral Approaches

These unintended impacts on migrant workers, in turn, have unintended repercussions on overall societies, economies and public health. Migrants themselves are not a health threat, but it is rather a system’s inability to provide accessible COVID-19 testing and treatment services along the migration continuum that is a threat to communities. Mobility is an inevitable reality and a necessity for functioning in our current globalized world. As governments are gearing to reopen their borders and economies, mobility will continue to link areas of high and low transmission well into the future. Inclusion protects migrants and the communities they reside in. Excluding this section of the population would ultimately cost every national and regional effort to flatten the curve.

Border checkpoint Aranyaprathet July 2020. Photo Source: IOM

Furthermore, inclusion must be multi-sectorial. National Response plans should specifically and robustly promote migrant outreach and inclusion in prevention, testing, treatment, surveillance and mitigation measures in a linguistic and culturally appropriate way. Addressing stigma and discrimination towards migrants within the host communities is essential to enhance their service-seeking behaviours. Collaborating with a wide range of relevant government sector and agencies is pivotal to tackling the socio-economic impacts on migrants who’ve lost their jobs. And monitoring the impacts of public health measures on mobility and mitigation strategies is essential to not only evaluate their effectiveness, but also to build capacity for better managed migration in a COVID‐19 world.

IOM highlights four key policy considerations to incorporate migration in the COVID-19 response. Firstly, understanding that migration dynamics, migration health and mobility management goes beyond borders. Response should not be limited to only strong points of entry measures and restrictions. Noting the migration patterns, mapping vulnerable hotspots, spaces of social interaction (such as border markets, food stalls etc.), at-risk communities and health risks, as well as assessing existing public health capacities for current gaps and additional operational needs required to extend services to them is a vital first step (IOM HBMM 2016, 4-5). This would help define public health interventions, scaling up community-based activities, enhance cross-border coordination and in turn strengthen health systems.

Secondly, developing strong multi-sectoral collaborations among various government bodies, partners and agencies to ensure all mobile populations including internally displaced people, tourists, expatriates, students and diplomats are being included in the COVID-19 response. Identifying the gaps and synergies between different agencies and partners would maximize the availability of the social welfare assistance that have been rolled out to brace the consequences of the shutdowns, which migrants are currently left out of. Migrants are essential for economic recovery, and hence a strong call for their inclusion in cash disbursements, insurance programs, remittance services, ensuring occupational health and safety in needed.

Thirdly, leveraging existing blueprints available on migration health policies to empower governments to implement the COVID-19 response along the mobility continuum. Migration health has been constantly aiming at global and regional platforms such as within the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), WHO’s Global Action Plan for Promoting the health of refugees and migrants adopted at the 2019 World Health Assembly, Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) legal frameworks and policies on the protection and promotion of migrant worker’s rights and within several other specific disease control programs such as the End TB Strategy and Joint United Nations Initiative on Mobility and HIV/AIDS (JUNIMA).

Finally, the last and important recommendation is Universal Health Coverage (UHC). It is important to realize that health coverage is not truly “universal” unless migrants are included. UHC redefines health care beyond the basis of citizenship and reimagined to transcend national borders. This globally agreed upon goal ensures coverage for every individual within a given territory including migrant workers and irregular migrants, covering services for COVID-19 without any discrimination and promoting financial risk protection to reduce out-of-pocket payments (Guinto, R.L., 2015). Thailand’s comprehensive health policy does include everyone, including undocumented migrants, and meets the goals of UHC independent of legal status. However, as the current situation is rapidly fluctuating governments, including Thailand, have struggled to adapt their agreements, policies, surveillance arrangements and public health measures accordingly, leaving the commitment towards UHC to potentially fall back. Hence, attention should be paid to implement UHC programs robustly enough to acclimatize to any new shocks precipitated by the pandemic (Samman 2020, 3-4).

No One is Safe, until Everyone is Safe

The GMS will continue to experience migration in the coming decades, regardless of how this or other pandemics will progress. Millions of migrants employed across the GMS are the unsung heroes that work on farms, in fisheries and forests to maintain food supplies; in the construction sectors they continuously upgrade our infrastructures; and they are employed in in transportation, tourism, textile and several other unrecognized essential industries, including at present working on the frontlines fighting the pandemic. Hence, health equity through migrant-inclusive systems and strategies is of great importance to advance health security, recovery, and the resilience of our society overall. Deliberate policy decisions that support initiatives for irregular migrants could go a long way in addressing their crucial needs as a matter of human rights. Placing women’s economic recovery at the centre of responses is critical for stimulating long-term economic recovery as well. And finally, truly acknowledging that people on the move are a part of the solution. Countries need to validate their work by maximizing their contributions and exploring options to regularize them. This will also benefits migrant-sending countries through the remittances they receive, and the knowledge and skills exchanged. Collectively utilizing every single individual’s potential, and that of all types of migrant workers will ultimately be the panacea needed to build an inclusive, equal and resilient society we need coming out of this crisis.

24 August, 2020

References

- Asian Development Bank, 2013. Facilitating Safe Labor Migration in the Greater Mekong Subregion Issues, Challenges, and Forward-Looking Interventions. Asian Development Bank.

- Guinto, R. L., Curran, U. Z., Suphanchaimat, R., & Pocock, N. S. 2015. Universal health coverage in ‘One ASEAN’: are migrants included? Global Health Action, 8, 25749. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.25749

- International Labour Organization (IOM). 2020. Protecting migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic Recommendations for Policy-makers and Constituents. Policy Brief

- International Organization for Migration Press Release. 2020. Combatting Xenophobia is Key to an Effective COVID-19 Recovery. https://www.iom.int/news/combatting-xenophobia-key-effective-covid-19-recovery. (Accessed 18 August, 2020).

- ーーー. 2004. Glossary on Migration. International Organization for Migration.

- ーーー.2015. Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda: The importance of migrants’ health for sustainable and equitable development. Migration and health position paper. International Organization for Migration.

- ーーー.2016. Health, Border & Mobility Management IOM’s Framework for Empowering Governments and Communities to Prevent, Detect and Respond to Health Threats Along the Mobility Continuum. International Organization for Migration.

- ーーー.2020. Cross-Border Human Mobility Amid and After COVID-19. Policy Paper. International Organization for Migration.

- ーーー.2020. IOM Thailand COVID-19 Appeal. International Organization for Migration.

- McMichael, C., & Healy, J. 2017. Health equity and migrants in the Greater Mekong Subregion. Global Health Action. 10(1), 1271594. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1271594 (Accessed 18 August, 2020)

- Samman, E. (2020). Towards Universal Health Systems in the Covid-19 Era. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/200919_uhc_covid19_final.pdf(Accessed 20 August, 2020)

- The World Bank, 2020. Food security and COVID-19. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19. (Accessed 23 July 2020)

- United Nations Women. 2020. Addressing the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women Migrant Workers. Guidance Note, 1-6p. https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/guidance-note-impacts-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-women-migrant-workers-en.pdf?la=en&vs=227 (Accessed 20 August, 2020)

- World Health Organization. n.d. Migration and Health: Key Issues. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migration-and-health-in-the-european-region/migration-and-health-key-issues#:~:text=In%20spite%20of%20the%20common%20perception%20that%20there%20is%20a,in%20Europe%2C%20independently%20of%20migration. (Accessed 18 August, 2020)

Dr. Suraksha Chandrasekhar serves as the Emergency Health Support Consultant for the International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. She is currently providing technical support for IOM’s COVID-19 coordination and response efforts in the Asia-Pacific region. Upon graduating from Medical School, Dr. Chandrasekhar completed her Master’s in Disaster Medicine and Humanitarian Assistance from Thomas Jefferson University (USA) and had gone to work for the United Nations Secretariat in New York, where she provided technical and logistics assistance for the 2018 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak to the Department of Peace-Keeping Operations. She has previously worked for the American Red Cross (Philadelphia) and Life Again Foundation, a local NGO in India, in the field of disaster management, gender-based violence and reproductive healthcare, and advocacy for health rights and coverage, during humanitarian emergencies.

Dr. Montira Inkochasan, a Ph.D. in Applied Behavioural Science Research, is the Regional Migration Health Programme Support Officer for the International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. She has been working for IOM for 14 years supporting migration health projects and activities in Asia and the Pacific. Dr. Inkochasan has been providing technical supports to IOM’s migration health programme on HIV, TB, Malaria, pandemic, and emerging infectious diseases projects through supporting the development of concept papers, presentations, and reports through quality operational research, impact evaluations and reporting on key migration health themes and topics. She leads and/or provides oversight in qualitative, quantitative and applied research studies, mapping of mobility and health services, and development of behaviour change communication at the country and regional level. She has been involving in research work intensively for more than 10 years in wide range of issues and areas, namely in the fields of social, health, education and marketing. She managed IOM office and migration-related projects in Lao PDR for four years before joining the Migration Health Unit at the IOM Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

Dr. Patrick Duigan has been working in the field of migration health for the past 12 years in a range of humanitarian and development settings. He is currently serving as the Regional Migration Health Advisor with the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, based in Bangkok. In this capacity, he provides support and advice to IOM Country Missions, governments and local, regional and global partners to promote the migration health agenda across the Asia Pacific. Dr. Duigan completed medical school in Australia and has undertaken graduate study in Public Health, Tropical Medicine, Humanitarian Assistance and Child Health with Adelaide University, James Cook University, LSHTM, Liverpool School of Topical Medicine. Dr. Duigan has worked in numerous countries including Australia, PNG, Cambodia, Myanmar, Haiti, Philippines, Nepal and Thailand on a range of migrant health related programs including TB, HIV and Malaria Programming, Health System Strengthening approaches, emergency response and recovery and analysis and development of migration health policies. He has co-authored several publications on migrant health including those appearing in the BMJ, SEARO journal of Public Health and the Health and Human Rights Journal.

Citation

Suraksha Chandrasekha, Montira Inkochasan and Patrick Duigan. 2020. “No one is safe, until Everyone is Safe: Migration and COVID-19 in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS)” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.