Presentation

|

SpeakerPravit Rojanaphruk(Khaosod English) |

Abstract

I will focus on how that Thai government has succeeded in dominating the narrative about the danger of COVID-19 to the point where the country is gripped with even one new case of local infections. It also comes with a heavy price on the economy and the majority of the press support prolonged isolation of Thailand from the mass tourism at a heavy price only. Essentially only one narrative, one filled with zero-tolerance for new infections dominates the Thai press.

The story of how Thai press report the spread of COVID-19 pandemic was that of a near total domination by the state’s narrative that led to no challenge to the course of actions taken by the state, despite severe economic repercussions and some impact on individual rights.

The domination by the state’s discourse on what Thailand needs to do began with the creation of the COVID-19 Centre enlisting senior officials from various ministries including Defense, Foreign Affairs and Public Health. Dr Taweesin Wisanuyothin, was appointed the spokesperson of the Government’s Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration. Taweesin is a trained psychiatrist and former director of the Galaya Rajanakarinda Institute of the Department of Mental Health. He is fairly good-looking, but most importantly, very persuasive. Much of the credit for the government of Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-ocha in managing to convince both the press and the large swath of the Thai population to support the government’s drastic measures which includes the imposition of the emergency decree has to do with Taweesin’s persuasive prowess in front of daily televised briefly on most television channels in the first few months since the spread of COVID-19 earlier this year.

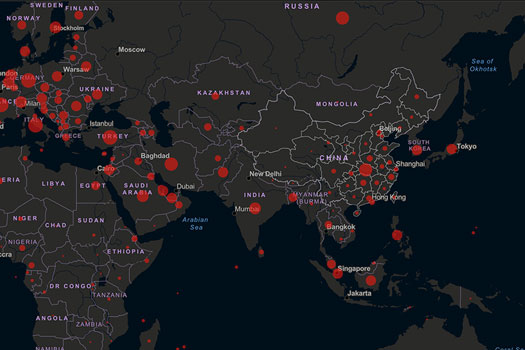

At the heart of Taweesin’s argument is the daily report on how bad other nations were doing and what will become of Thailand if it doesn’t take swift measures, including the de facto shutting down of Thai airspace from tourists in the first six months or so since the spread of the virus. Countries with widespread COVID-19 have been cited in the daily televised report at 11.30 aired on all major television stations. Particular focus is on countries with major challenges such as China, South Korea, Singapore, Indonesia, Italy, France, the UK and the United States.

Pride of a nation

A most important figure presented in the daily report, analysis and briefing by the center and reported by the Thai press is one comparing where Thailand stands compared to other nations, particularly wealthier and more developed or advanced ones. The daily report has become a subconscious national competition, a COVID-19 Olympic if you will. Here, on the tabulation of COVID-19 situations, nation states with better ranking would be less infected, with less deaths and fewer new infections.

According to such a table reported by the center and reproduced by the local media including The Bangkok Post, Thailand as of 9 Dec. 2020 is ranked at Number 151 and is doing far better than most other countries around the world including its neighbors. The table, which appeared on page two of the printed version of The Bangkok Post in the 10 December edition, listed 50 most affected countries with many vital stats and ended with Thailand at Number 1511.

Among the ‘top’ 50 listed were Indonesia, ranked at Number 20 from around the world, with 592,900 accumulated infections, 18,171 deaths and 487,445 recovered. The Philippines, meanwhile, was ranked at Number 27 with 444,164 accumulated infections, 8,677 deaths and 408,942 recovered. Japan meanwhile was ranked on that day at Number 46, or the 46th worst hit nation on earth. Japan recorded a total of 163,929 accumulated infections, 2,382 deaths and 138,994 people recovered. As for Thailand on that day, she was ranked at Number 151 with total accumulated infections of ‘only’ 4,151 people, with ‘just’ 60 deaths and 3,880.

No one can see how this COVID-19 could turn into a de facto national pride competition. Never mind if Thailand enjoyed almost 40 million, or 39.8 million, foreign visitors in 2019 and tourism and the inbound tourism industry is a major income earning industry for the kingdom.

According to a report by Kasikorn Bank report for 20202, the group market for foreign tourists arriving in Thailand includes visitors from Japan, South Korea, Germany, France and India. This year, Thailand witnessed a near total plunge in the number of tourist arrivals. Despite that, hotel and travel industries have decided to go along with the government’s measures and opted for the government’s assistance such as bank and loan measures to assist them while most foreign tourists were gone instead.

Zero tolerance and paranoia

By December, despite Thailand faring well very well when it comes to COVID-19 rankings, the number of deaths and new infections, the government, media and public remain highly fearful of a new outbreak and highly sensitive to even a few cases of new infections.

The government’s success in instilling fears in the mind of the Thai people means wearing sanitary masks became second nature for most Thais, particularly in dense urban areas in Bangkok and elsewhere. There are no anti-mask protests in Thailand, unlike in countries like the United Kingdom and Germany. What’s more, the media and Thais keep close watch on new infections with detailed tracing information such as where newly discovered infected persons have visited, as well as a timeline of his or hers whereabouts and more.

For example, there was the latest bout of a few new infections were Thais who returned from Myanmar’s bordering province of Tachileik3. The news dominated news headline, on the same edition of The Bangkok Post of that day, for example carried the headline ‘Fear over Myanmar strain’ with a sub headline stating that the government says the few infected returnees were not super spreaders4.

To give you a glimpse of the detailed report about new infections, consider the following quotes from the same news article from the front page of Dec 10 edition.

‘Over 5,100 at-risk people who had been in contact with the infected returnees had been tested. The only person who tested positive was a friend of the returnees and they had travelled together, said the doctor.’

‘Director of the Division of Communication Diseases, Sopon Iamsirithaworn, said all 55 people who had been in contact with a 51-year-old infected woman from Sing Buri had tested negative for the virus.’

‘Passengers on Nok Air flight DD8717 – the flight she and two of the infected returnees travelled on – all tested negative.’5

Be that as it may, domestic tourism industry in Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai provinces have been affected as these were the two provinces where newly-infected returnees who did not report for state quarantine spent time before being discovered to be infected.

Lacking human rights aspects

With the government successfully instilling deep fears about possible COVID-19 infections, it’s not just the tourism industry that has been deeply impacted, but some aspects of human rights have also suffered. Thailand has been under continued renewal of the imposition of the state of emergency for over half a year now. This enables the government to restrict people’s movement and possibly order a new lockdown although as of present (11 Dec 2020 at time of writing), the government has denied that there is a need for a new lockdown which includes limiting transports, restaurant services, business operation time and night time curfew. The health-related state of emergency, which certainly affects some human rights, is currently extended until the mid of Jan 2021 and could be extended again.

A matter of medical expertise

In the final analysis, another key factor affected Thai media’s docile reporting about the COVID-19 pandemic is the deep-rooted inequality between experts and non-experts in Thai society. Medicine is a highly professional field and unlike some more developed countries, the Thai press has no tradition of recruiting medical professionals to do medical news coverage.

Like much of the rest of Thai society, the press feel that this is something best left to the experts in the medical field and the Thai government has ‘successfully’ managed to deploy medical experts to dominate the narrative about the spread of COVID-19 and how to deal with it. This has been to the point where there exists no meaningful counter narrative, alternative narrative or resistance.

If anything, countries like the United States where a vocal, but small number of populations deny the existence of coronavirus have reinforced the feelings among the Thai press and the Thai public that the government was on the right track, due to the very high number of deaths that the infected in the US. This is despite deep economic impacts due to the severe restriction of foreign tourist arrivals, currently limited to 1,200 foreign tourists per month and a 14-day quarantine period before being let free outside the hotel. The Thai government has managed to convince the majority of the press and the Thai public that this is the only way to go, no matter what the costs.

Notes

- 1 Kasikorn Bank. 2020.K SME Analysis: Jap Chiphajon Nak Thong Thiaw Tang Chat Pi 62 [Checking the Pulse of Foreign Tourists, Year 2020]. P.3. Available online at: https://kasikornbank.com/th/business/sme/KSMEKnowledge/article/KSMEAnalysis/Documents/SME_Analysis_Jan.pdf (Accessed 14 December, 2020)

- 2,3 The Bangkok Post. 2020. “Fear Over Myanmar Stain”. 10 December, 2020. Available online at: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2032735/fear-over-myanmar-strain

- 4,5 Ibid.

- Pravit Rojanaphruk is a senior staff writer at Bangkok-based Khaosod English online news. He was awarded the International Press Freedom Award for 2017 by the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. He was educated at the University of the Philippines and Oxford University. Pravit was detained twice without charge by the Thai military junta after the May 2014 coup.

Comment

|

DiscussantEdoardo Siani(Ca’ Foscari University of Venice) |

Pravit Rojanaphruk spoke at length about the media’s overreliance on the government’s narrative of the COVID-19 health crisis in Thailand. This narrative, of Thailand being one of the few countries in the world to effectively contain the virus,1 had been enormously successful, at least until the sudden spike of late December 2020.2 To what degree, however, is this narrative reliable? Scholars stress that Thailand has a long history of narratives of “exceptionalism.”3 These include the idea that the country has never been colonized, unlike other countries in the region; the idea that the national land is beautiful and fertile like no other; the idea that the Thai people have a relationship with their kings that no other nation can understand, and so on. Thailand’s COVID-19 story plays into this trope. Indeed, the explanations invoked locally to make sense of the very low infection numbers display familiar nationalist undertones: some say that the weather is inimical to the virus; other argue that the Thai people have unique personal hygiene habits and diligence. Such explanations seem particularly feeble if one considers that the same climatic and cultural factors exist in other Southeast Asian countries that record high COVID-19 numbers. The continuity between the official narrative and such nationalist tropes obviously raises concerns. One cannot help wondering, for example, if there is adequate access to testing, or if COVID-19 cases may, for whatever reason, have been categorized as other diseases (for example lung infections or the flu)—a concern that has also been raised in other countries. Have and should journalists question the numbers provided by the government?

Pravit justifies his concern by describing how the uncritical portrayal of the COVID-19 crisis seems to interest only some, more mainstream, media. Yet in fact, journalists such as Pravit have been critical both in newspapers and on social media. For example, the government was roundly criticized in January 2020 when it refused to immediately shut down the country to tourists from China, putting economic interests before people’s safety.4 Liberal journalists were also critical of the government’s repeated refusals to lift the state of emergency, originally declared in late March 2020,5 although the official infection figures remained low for months. As far as I know, there has been no backlash directed at such journalists. The risk of social sanction is also quite low: outspoken journalists have been applauded by the many young people, who, from February to December 2020 (with a pause from March to July) have protested against the government. Why, then, have many journalists accepted the government’s narrative uncritically? We must ask, what specific dynamics prevent journalists from critiquing the government’s narrative?

I agree that there are enormous human rights issues in Thailand, especially with the present administration. This is a military government dressed as a civilian one. It came to power through a coup d’état, confirmed its power through a controversial election last year, and has showed contempt for human rights throughout its tenure. I also agree that the government has invoked the COVID-19 crisis to manage unwanted political protests, most clearly in late March 2020, when it successfully suppressed the first round of rallies via the declaration of a state of emergency. The protests, however, resumed in late July despite the state of emergency, and continued in full force until late December, when key leaders announced a pause for reasons unrelated to COVID-19.6 What I find remarkable in all this is that, so far at least, the government has not particularly exploited the international COVID-19 crisis and the related state of emergency to ban the protests. Instead, they have used less international acceptable legal instruments, such as sedition and lèse majesté (royal insults). Both sedition (invoked to charge protesters who allegedly “blocked” a royal motorcade)7 and lèse majesté are far more questionable strategic choices. They draw attention to the monarchy and its critics, feeding into debates about the controversial, anachronistic, and draconian nature of such laws. Their invocation is also very problematic from the perspective of human rights—in Thailand and beyond. Liberal individuals in presumably democratic countries, especially in the so-called West, have accepted drastic limitations to their liberties in order to contain the health emergency; they would have likely taken the invocation of an emergency decree to curb COVID-19 as a far more legitimate means than sedition and lèse majesté in quelling the protests. So why has the government not invoked COVID-19 as a more acceptable tool of repression? Will they seek to invoke it now that the infection numbers are growing?

Notes

- 1 Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) Newsroom. 2020. “Thailand ranked second best in the world for ongoing COVID-19 recovery,” 15 June. Available online at: https://www.tatnews.org/2020/06/thailand-ranked-second-best-in-the-world-for-ongoing-COVID-19-recovery/ Accessed 6 January, 2021.

- 2 BBC. 2020. “COVID-19: Thailand tests thousands after virus outbreak in seafood market,” December 21. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55391417 Accessed 6 January, 2021.

- 3 See, for example, Harrison, R. and Jackson, P. (eds.). 2010. The Ambiguous Allure of the West: Traces of the Colonial in Thailand. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- 4 Reuters. 2020. “Public anger grows over coronavirus in Thailand, with eight cases of the illness,” 26 January. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-china-health-thailand/public-anger-grows-over-coronavirus-in-thailand-with-eight-cases-of-the-illness-idUKKBN1ZP0FP Accessed 6 January, 2021.

- 5 Reuters. 2020. “Thai leader to invoke emergency powers as virus infections climb,” March 24. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-thailand-emergency/thailand-to-declare-one-month-emergency-on-march-26-prime-minister-idUSKBN21B0RV Accessed 6 January, 2021.

- 6Reuters. 2020. “Thai protesters to pause now and return next year.” 14 December. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-protests-idUSKBN28O15O Accessed 6 January, 2021.

- 7 Khaosod English. 2020. “PM orders prosecution of protesters who ‘blocked royal convoy.’” 15 October. Available online at: https://www.khaosodenglish.com/news/crimecourtscalamity/2020/10/15/pm-orders-prosecution-of-protesters-who-blocked-royal-convoy/ Accessed 6 January, 2021.

Edoardo Siani is an assistant professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. He writes about power in Buddhist Thailand. Edoardo received a PhD in anthropology and sociology from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and was a postdoctoral fellow and assistant professor at Kyoto University’s CSEAS. A resident of Bangkok since 2002, he taught at Thammasat University, worked in language education, and served as an interpreter for the Thai police. He has contributed to media outlets including the BBC and The New York Times.

Other Presentations

- Slow Virus Response, Quick Rights Suppression: The Philippine Covid-19 Experience

- Reporting on Covid-19 amidst Political Upheaval in Malaysia

- Is the COVID-19 Lockdown Undermining Journalism in Myanmar?

- Regressive Indonesian Freedom? The Rise of Digital Harassment against Journalists and Civil Society in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic