Partly because of lack of mass testing (Mendoza et al. 2021) and effective contact tracing (Hapal 2021), the Philippines remains a COVID-19 hotspot with 52,029 “active cases” as of 27 June, 2021 (Philippine Department of Health/DOH 2021). At 223.18 deaths per million people, the Philippines has the most “cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths” among Southeast Asian countries plus Japan and South Korea, as of 26 June, 2021 (John Hopkins University data in Our World in Data 2021). Thus, like many Filipino academics, we support calls for the Philippine government to adopt a more effective, more scientific, and more data-driven pandemic response. I have written papers on socialist(ic) responses to the pandemic (San Juan 2020), on supplementary economic aid during the pandemic (San Juan 2020), and on mass testing and nationalization of hospitals (San Juan 2020), hoping to influence policy or at least popularize some solutions to the crises that the pandemic brought to us all. Early this March, along with more than 400 academics, we urged the Philippine government to “channel all its energies and resources into a pandemic response – especially on contact tracing, mass testing, and mass vaccination, and additional cash aid for both poor and middle-class families hit hardest by the crisis that the pandemic partly caused” (Academics Unite for Democracy and Human Rights 2021). Barely two months hence, I became part of the so-called “active” COVID-19 cases in my country. This is a short account of how we survived COVID-19 and more.

On 24 May, 2021, my brother – who works for a privately-run train company, complained of losing his sense of smell and taste. We immediately self-quarantined and sought COVID-19 Swab RT-PCR Tests on the next day via a private stand-alone laboratory, as hospital laboratories are busier (though a cheaper option). Our swab test expenses – worth 6,000 pesos (roughly US$125) or almost 14 times the current real daily minimum wage in Metro Manila (National Wages and Productivity Commission 2021) – were not reimbursed by our Health and Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) or private insurance providers. In my case, it’s because I’m asymptomatic, for whom this DOH recommendation (2020) applies: “(c)lose contacts who remain asymptomatic for at least 14 days from date of exposure can discontinue their quarantine without the need of any test.” In my brother’s case, it’s because he did not consult his HMO’s accredited doctor first. Meanwhile in most of Europe, swab tests for symptomatic individuals are free of charge (Wintle 2021), while in Singapore, swab tests are free “for target groups from the general community who are well or have been diagnosed with acute respiratory infection” (Singapore Ministry of Health 2021).

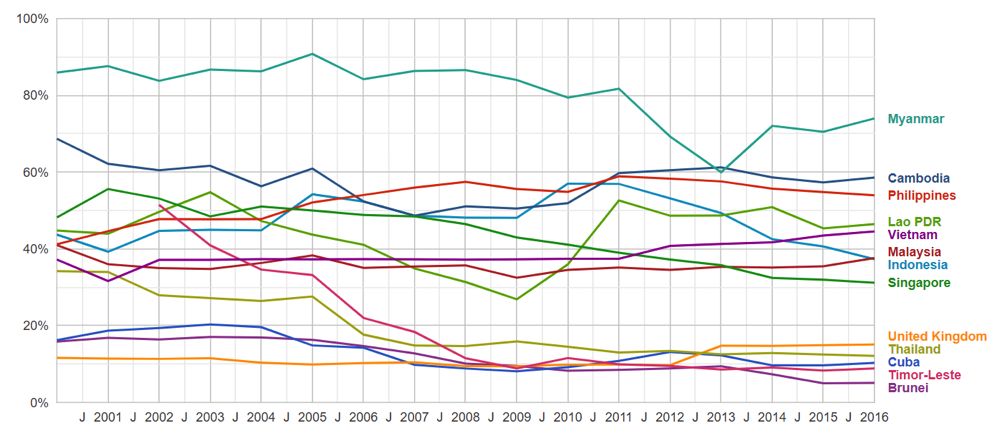

Our positive swab test results were released the day after we were tested. Same-day results can be had for 5,000 pesos (US$100) per swab test. Following the capital city’s Barangay (Village) Health Emergency Response Team (BHERT) protocols, we self-quarantined for 14 days (Manila City Government 2020). Our health regimen then included healthy and nutritious meals ranging from sinigang na bangus (milkfish in sour broth) or daing na bangus (milkfish marinated in nipa vinegar, salt, lots of garlic, ground pepper, and then fried) and nilagang tadyang ng baka (boiled beef ribs with vegetables) and fruits such as bananas and oranges, doses of Vitamin C and Zinc, and Virgin Coconut Oil or VCO – “a potential antiviral agent against COVID-19” according to Dr. Fabian Dayrit’s Philippine Council for Health Research and Development-funded research (PCHRD 2020), but more research would have to be conducted on this. There are few other studies to support such use at present (see Angeles-Agdeppa et al. 2021; Tan-Lim and Martinez 2020), but we still asked our siblings to buy some for us, as these are widely available in local pharmacies. We are lucky in that we can afford such fairly costly home-based treatment. It’s admittedly out of reach for many unemployed and underemployed Filipinos whose numbers certainly swelled because of the pandemic’s negative economic impact. We’re also very lucky not to have developed symptoms (other than my brother’s temporary loss of his two senses), because severe symptoms would have meant hospitalization – a nightmare in these times and always in a country like the Philippines where out-of-pocket payments (OOPPs) for health expenditures are third worst in Southeast Asia (Figure 1). The Philippines’ data for OOPPs are also far worse than the statistics in Cuba and the United Kingdom, two ideologically different countries which nevertheless both maintain robust publicly-funded healthcare systems which can serve as role models for countries where health systems are weaker.

Figure 1. Out-of-pocket payments (OOPPs) as % of Current Health Expenditure in Southeast Asian Countries, Cuba, and the United Kingdom (2000-2016) 1

Beyond 786,384 pesos (US$16,197) – the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation’s maximum “case rate” for critical pneumonia (PhilHealth, 2020) – COVID-19 hospitalization costs would compel individuals to spend for OOPPs, unless if you have a supplementary private insurance provider that can help reduce costs but won’t wipe out all OOPPs as the final bill can reach million-peso figures (Magsambol 2020). Hence, due to the inadequacy of the privately-supplemented public health insurance in the Philippines, many Filipino families resort to online medical crowdsourcing to partly finance their hefty COVID-19 costs. Of course, some would say those who were hospitalized are still the lucky ones as some have died in agony in tents near health care facilities, while waiting for emergency care hospital beds to become vacant (McCarthy 2021). The pandemic has only further exposed existing gaps in the country’s health care system. For example, two years before the pandemic, DOH (2018) summarized the country’s gaps in hospitals beds thus: “The total hospital bed capacity of the country is 101,688 beds, with government hospital beds accounting for 47 percent (47,371) and private hospitals beds for 53 percent (54,317). On the average, one hospital bed served 1,010 people in 2016” indicating “a gap of 1,022 hospital beds…” Philippine government spending remains perennially low for public health care with the domestic general government health expenditure per capita in current dollars never reaching $50 from 2000-2016. This is in contrast with Cuba’s statistics which range from a low of more than $100 to a high of more than $800 (San Juan 2021). The Philippines suffers from a decades-old labor export policy that provides health care personnel to many developed countries despite a lack of sufficient personnel for local needs (San Juan 2014). And this has drastically limited the national health care system’s capacity to swiftly and effectively respond to pandemic-era needs.

Early vaccination could have saved us all from COVID-19 infection. My brother (as well as my other siblings) is part of the A4 vaccine priority group which includes “private sector employees who are required to work outside their places of residence” according to the Philippines’ Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases Resolution No. 117 (2021). Manila only started accepting those in the A4 category for “walk-in” vaccinations on 3 June, 2021 (Sarao 2021) during which we were still under home quarantine. Meanwhile, I’m part of the A3 category (those with comorbidities, obesity, in my case). I was waiting for an A3 vaccination schedule when COVID-19 hit us, and unfortunately, my vaccination would have to wait – as many vaccination centers now prioritize A2 (citizens aged 60 up) and A4 categories only. Hence, we have immediately preregistered our parents (A2 category) for vaccination. In Manila, preregistered individuals can “walk into” any vaccination center if it was announced on the city government’s Facebook page that they will be accepting certain categories on a particular day. I wrote a letter on behalf of the Professionals for a Progressive Economy (PPE) – a volunteer-run network that advocates for 100% free health care and reduced personal income tax rates and explained what I saw and experienced. On our first attempt (14 June, 2021), as I detailed in a public letter to the city government, we “personally witnessed how the current system causes exhaustion on the part of preregistered citizens who reach the venues after the typical 2,000 slots per mall have been filled in (as early as 4am, based on online citizens’ posts or shortly before 6am, based on the undersigned’s experiences). A security guard in a mall also told the undersigned that people started lining up as early as 12:00 midnight!” In the letter I suggested “adopting a scheduled appointment system for vaccination (after preregistration) – with definite time slots for every preregistered citizen, rather than carry on with the current “walk-in” system.” Furthermore, I asked them to “consider reverting to a system of having more vaccination sites beyond the four big malls of Manila.” Our experience clearly shows that vaccine hesitancy is no longer a problem in the Philippines. People are lining up at early dawn to have a chance to get vaccinated. Citizens are also flooding vaccine-related Facebook announcements of local government units with their comments and complaints on the lack of ample vaccines (see threads in the official Facebook pages of the Manila City Government and Quezon City Government for examples). Cities as far as Cagayan de Oro in the president’s home region of Mindanao are asking for additional vaccines (ABS-CBN News 2021).

On our second attempt (15 June, 2021), we knew we had better chances as there were 2,500 slots for every vaccination site announced (in the four big malls again). We woke up at around 2:50 am, and after some coffee, at around 3:15 am we departed. It was a swift ride to the vaccination center, a big Manila mall. At around 4:20 am, we started lining up in the wrong queue. Apparently, there are two queues: one for A2 (senior citizens) and one for A4. Security guards were very accommodating, but it would have been better if we had been informed about the two separate queues. Senior citizens were immediately given stubs and escorted to the cinema (the actual vaccination site; see photo below). Our mother and father were seated at around 5am, and from then on waited for vaccination to start at 6 am as announced. Vaccination started out late at around 6:43 am. They had their first dose at around 8:23am and then we had a late breakfast at around 10:20 am. We will return to a vaccination site on 13 July for their second dose. While this walk-in experience somehow worked for us, I think a scheduled one would still have been better and relatively stress-free. We are just relieved that our senior citizens have been vaccinated. We hope that the government can do the same for the rest of our country – quickly and smoothly.

Figure 2. Mobile phone camera shot of a vaccination center in a mall-based cinema. Source: Author

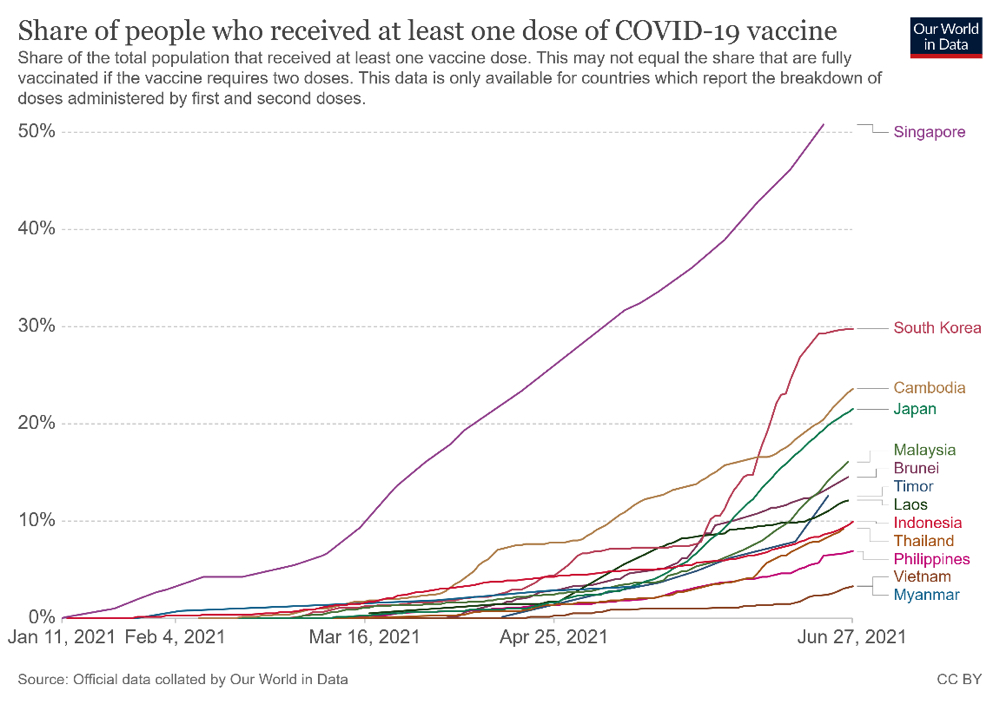

As of 13 June, 2021, herd immunity through vaccination is still a long way off as less than 5% of the Philippines’ population have “received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine” according to Our World in Data (2021). Among selected East and Southeast Asian countries, on the “share of the total population that received at least one vaccine dose,” the Philippines is behind all countries in Figure 3 (as of June 2021), though slightly ahead of Myanmar and Vietnam (data for Myanmar is until mid-May 2021 only). Unsurprisingly, a UK-based think tank Pantheon Macroeconomics that “(a)t the current pace of vaccinations in emerging Asian economies including India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam…the Philippines would be among the last to reach herd immunity,” for which “early 2023 probably is the best the archipelago can hope for” (De Vera 2021).

Figure 3. Share of people who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine in Selected East and Southeast Asian Countrie2

As a citizen of the Third World, I can only hope that our government will accelerate its vaccine acquisition plan, that the First World countries stop their unconscionable stockpiling of vaccines (Mullard 2020; Kelland 2021), and that current “trajectory of vaccine deployment” which unfortunately is being “determined by national competition and business profits, not by human need and cooperation” be reversed (Lapavitsas 2021).

The global NGO ONE estimates that “five countries (Australia, Canada, Japan, UK, and US) plus the EU bloc of 27 countries could share close to 1 billion doses of leading COVID-19 vaccines with other countries and still retain enough supply to inoculate their entire populations.” Such “vaccine nationalism” of developed nations will not only hamper quick global economic recovery but will also expose all countries to deadlier virus strains incubated by the lack of swift, vaccine-aided herd immunity (Mayta, Shailaja and Nyong’o 2021). Infectious waves of the Delta variant have been sweeping across numerous nations at present – including vaccinated citizens in countries such as Israel (Lieber 2021), which had been previously universally praised for quick mass vaccination (Glied 2021). Now, more than ever, as cliched as it may sound, no country is safe, until all countries are safe. Full-border shutdowns would not be feasible in an interconnected, hyperlinked global economy. Hence, the solution lies in practicing genuine cross-border solidarity and internationalism through the pooling of vaccine resources – including waiving patent rules and similar restrictions – and their more equitable distribution in all (and within) countries too (Progressive International 2021). In the meantime, with some colleagues, I have committed to swiftly writing on vaccination gaps and inequities in our country, towards the prospective improvement in practice as we enter into the end phase of this wretched pandemic era. We don’t even know if our policymakers will listen, but at least, as they say, it’s better to light a candle than to merely curse the darkness.

1 July, 2021

References

- Academics Unite for Democracy and Human Rights. 2021. Unity Statement of Academics Against the Recent Attacks on and Killings of Activists in the Philippines. https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?vanity=academicsunite&set=a.240544391111815. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Angeles-Agdeppa, Imelda et al. 2021. Virgin coconut oil is effective in lowering C-reactive protein levels among suspect and probable cases of COVID-19. Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 83, 104557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2021.104557. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- De Vera, Ben O. 2021. PH will be among last in Asia to achieve herd immunity – UK think tank. Inquirer, 22 June. https://globalnation.inquirer.net/197190/uk-think-tank-ph-among-last-in-asia-to-achieve-herd-immunity. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Department of Health. 2021. COVID-19 Case Tracker. 28 June. https://doh.gov.ph/2019-nCoV. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. 2018. National Objectives for Health: Philippines, 2017-2022. https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/publications/NOH-2017-2022-030619-1.pdf. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Glied, Sherry. 2021. Strategy drives implementation: COVID vaccination in Israel. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, Volume10, No. 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-021-00445-1. (Accessed 29 June, 2021). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13584-021-00445-1.

- Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2021. Resolution No. 117 Series of 2021. Official Gazette. 27 May. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2021/05may/20210527-IATF-RESO-117-RRD.pdf. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Kelland, Kate. 2021. Rich nations stockpiling a billion more COVID-19 shots than needed: report. Reuters. 19 February. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-vaccines-stockpili-idUSKBN2AJ00F. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Hapal, Karl. 2021. The Philippines’ COVID-19 Response: Securitising the Pandemic and Disciplining the Pasaway. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. 18 March. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868103421994261. (Accessed 29 June 2021).

- Lapavitsas, Costas. 2021. How Capitalist Competition Hobbled the COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout. Jacobin. 06 January. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/01/capitalist-competition-covid-19-vaccine-rollout. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Lieber, Dov. 2021. Delta Variant Outbreak in Israel Infects Some Vaccinated Adults. Wall Street Journal. 25 June, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/vaccinated-people-account-for-half-of-new-covid-19-delta-cases-in-israeli-outbreak-11624624326. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Magsambol, Bonz. 2020. Getting treated for coronavirus comes with a hefty price tag. Rappler. 17 April. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/getting-treated-coronavirus-price-tag (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Manila City Government. 2020. Barangay Health Emergency Response Team (BHERT). 16 March. https://manila.gov.ph/2020/03/barangay-health-emergency-response-team-bhert/. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Mayta, Rogelio, KK Shailaja and Anyang’ Nyong’o. 2021. Vaccine nationalism is killing us. We need an internationalist approach. The Guardian. 17 June. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jun/17/covid-vaccine-nationalism-internationalist-approach. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Mendoza, Abelardo Jose M. et al. 2021. The need for mass testing and the proper post-COVID-19 test behavior in the Philippines. Journal of Public Health, Volume 43, Issue 2, Pages e348 e349. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab065. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- McCarthy, Julie. 2021. Looking For A Bed For Daddy Lolo: Inside The Philippines’ COVID Crisis. NPR. 07 June. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/05/07/994187886/looking-for-a-bed-for-daddy-lolo-inside-the-philippines-covid-crisis. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Mullard, Asher. 2020. How COVID vaccines are being divvied up around the world. Nature. 30 November. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03370-6. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- National Wages and Productivity Commission/NWPC. 2021. Currengt Real Minimum Wage Rates. https://nwpc.dole.gov.ph/stats/current-real-minimum-wage-rates/. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- ONE. 2021. Rich countries on track to stockpile at least 1 billion surplus C19 vaccines. 18 February. https://www.one.org/international/policy/rich-countries-on-track-to-stockpile-at-least-1-billion-surplus-c19-vaccines/. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Our World in Data. 2021. Share of people who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. 14 June. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=PHL. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- ―――. 2021. Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people. 28 June. https://ourworldindata.org/. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. 2021. Share of people who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. 28 June. https://ourworldindata.org/. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Philippine Council for Health Research and Development/PCHRD. 2020. VCO a potential antiviral agent against COVID-19 — Filipino research. 05 October. https://www.pchrd.dost.gov.ph/index.php/news/6599-vco-a-potential-antiviral-agent-against-covid-19-filipino-research. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Philippine Department of Health. 2020. Department Memorandum No. 2020-0439. 06 October. https://doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/health-update/dm2020-0439.pdf. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

Philippine Health Insurance Corporation/PhilHealth. 2020. - PhilHealth guarantees continuing coverage for Covid-19 patients. 16 April. https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/news/2020/cont_coverage.php. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Professionals for a Progressive Economy/PPE. 2021. Letter to Mayor Isko Moreno Domagoso re: vaccination schedules. https://www.facebook.com/pro4pe/photos/a.1795048497341705/1824334384413116/. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Progressive International. 2021. Summit for Vaccine Internationalism. https://progressive.international/movement/campaign/summit-for-vaccine-internationalism-97d0efd9-db12-4d6e-8ba6-c840d319124a/en. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- San Juan, David Michael M. 2020. Responding to COVID-19 Through Socialist(ic) Measures: A Preliminary Review. SSRN. 24 March. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3559398. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. Economic Relief in the Time of COVID-19: Rationale, Mechanics, Costing, and Prospective Impact of Temporary Value-Added Tax (VAT) Suspension and Income Tax Waiver for the Poor and the Middle Class in the Philippines. SSRN. 10 April. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3571402. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. Panimulang Pagsipat sa Mga Modelong Tugon sa Krisis na Dulot ng COVID-19: Perspektibang Sosyalista sa Mass Testing at Nasyonalisasyon/Preliminary Analysis of Model Responses to the Crisis Brought by COVID-19: Socialist Perspective on Mass Testing and Nationalization. Kawíng Volume 4, No. 2, pages 1-41. https://psllf.org/kawing-4-2/. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. 2014. Pambansang Salbabida at Kadena ng Dependensiya: Isang Kritikal na Pagsusuri sa Labor Export Policy (LEP) ng Pilipinas/ National Lifesaver and Chains of Dependence: A Critical Review of the Philippine Labor Export Policy (LEP). Malay Voliume 27, No. 1. https://ejournals.ph/article.php?id=8066. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- ―――. 2021. Shaping the Agenda for the 2022 Elections: Building a National Health Services (NHS) for the Philippines Towards Achieving 100% Free Health Care for Everyone. Researchgate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352221975_Shaping_the_Agenda_for_the_2022_Elections_Building_a_National_Health_Services_NHS_for_the_Philippines _Towards_Achieving_100_Free_Health_Care_for_Everyone. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Sarao, Zacarian. 2021. Isko Moreno: Manila allows A4 walk-in vaccinations, including for non-residents. Inquirer. 03 June. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1440964/isko-moreno-manila-allows-a4-walk-in-vaccinations-including-for-non-residents. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Singapore Ministry of Health. 2021. Regional Screening Centres (RSCs). https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/rsc. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- Tan-Lim, Carol Stephanie C. and Martinez, Corinna Victoria. 2020. Should virgin coconut oil be used in the adjunctive treatment of COVID-19?. Acta Medica Philippina, Volume 54. 06 June. https://actamedicaphilippina.upm.edu.ph/index.php/acta/article/view/1606. (Accessed 29 June, 2021).

- Wintle, Thomas. 2021. Where do you have to pay for COVID-19 tests and how much do they cost?. CGTN. 21 January. https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2021-01-21/Where-do-you-have-to-pay-for-COVID-19-tests-and-how-much-do-they-cost–XbizvvKAlW/index.html. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

- World Bank. 2020. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure). 08 April. Google Public Data Explorer. https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_#!ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=sh_xpd_oopc_ch_zs&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=world&ifdim=world&hl=en_US&dl=en_US&ind=false. (Accessed 15 June, 2021).

Notes

- 1 World Bank data (2020) from Google Public Data Explorer.

- 2 From Our World in Data (2021)

Professor at the Filipino Department of De La Salle University-Manila (DLSU-Manila) and Affiliate at the Southeast Asia Research Center and Hub (SEARCH) in the same university. Currently, a PhD in Development Studies (Research Track) student at the Political Science Department of DLSU-Manila. Lead Convener of the Professionals for a Progressive Economy (PPE) and Associate Member of Division I (Governmental, Educational and International Policies) of the National Research Council of the Philippines (NRCP).

Citation

David Michael M. San Juan. 2021. “Surviving COVID-19 and Seeking Vaccination: Stories and Notes from Manila, the Philippines” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.