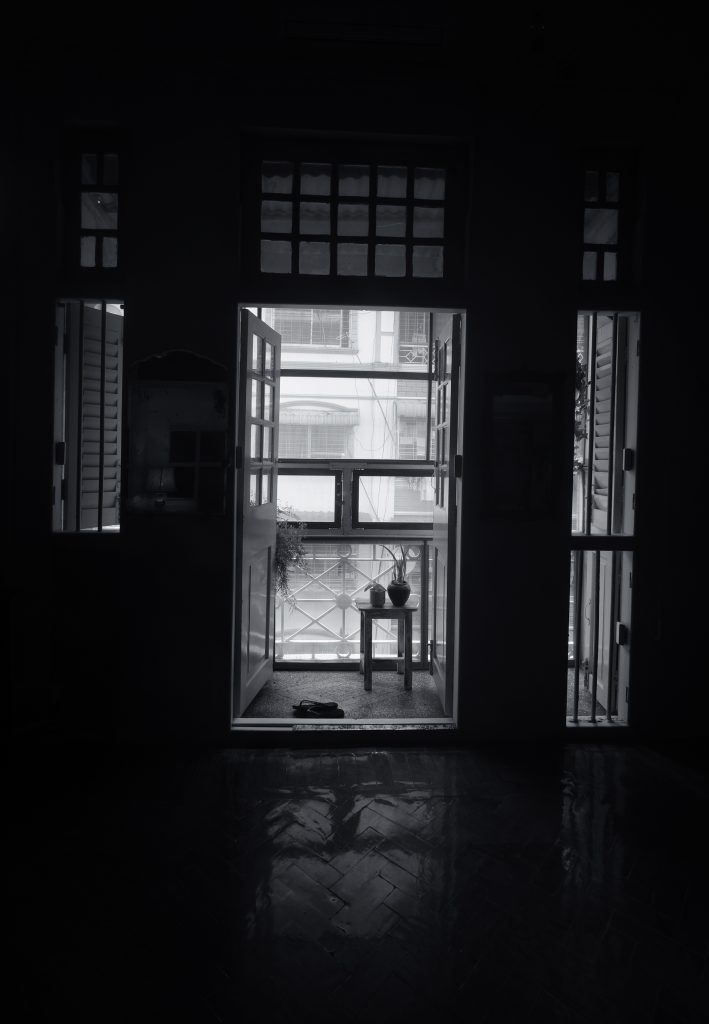

The honking and street peddlers’ calls have gone quiet. From my tiny downtown balcony I listen to crows and ambulances occasionally piercing the unfamiliar silence.

A building placed under quarantine after a new case has been found. All residents were moved to a community quarantine centre.

Residents standing in line to get tested at the National Health Laboratory in Dagon township, which remains the country’s main testing laboratory for COVID-19. As of 28 September, the case positivity rate in Myanmar averaged at 15 percent. Frontier Myanmar reported that only a handful of countries had higher case positivity rates at that time: Iraq, Tunisia, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Argentina.

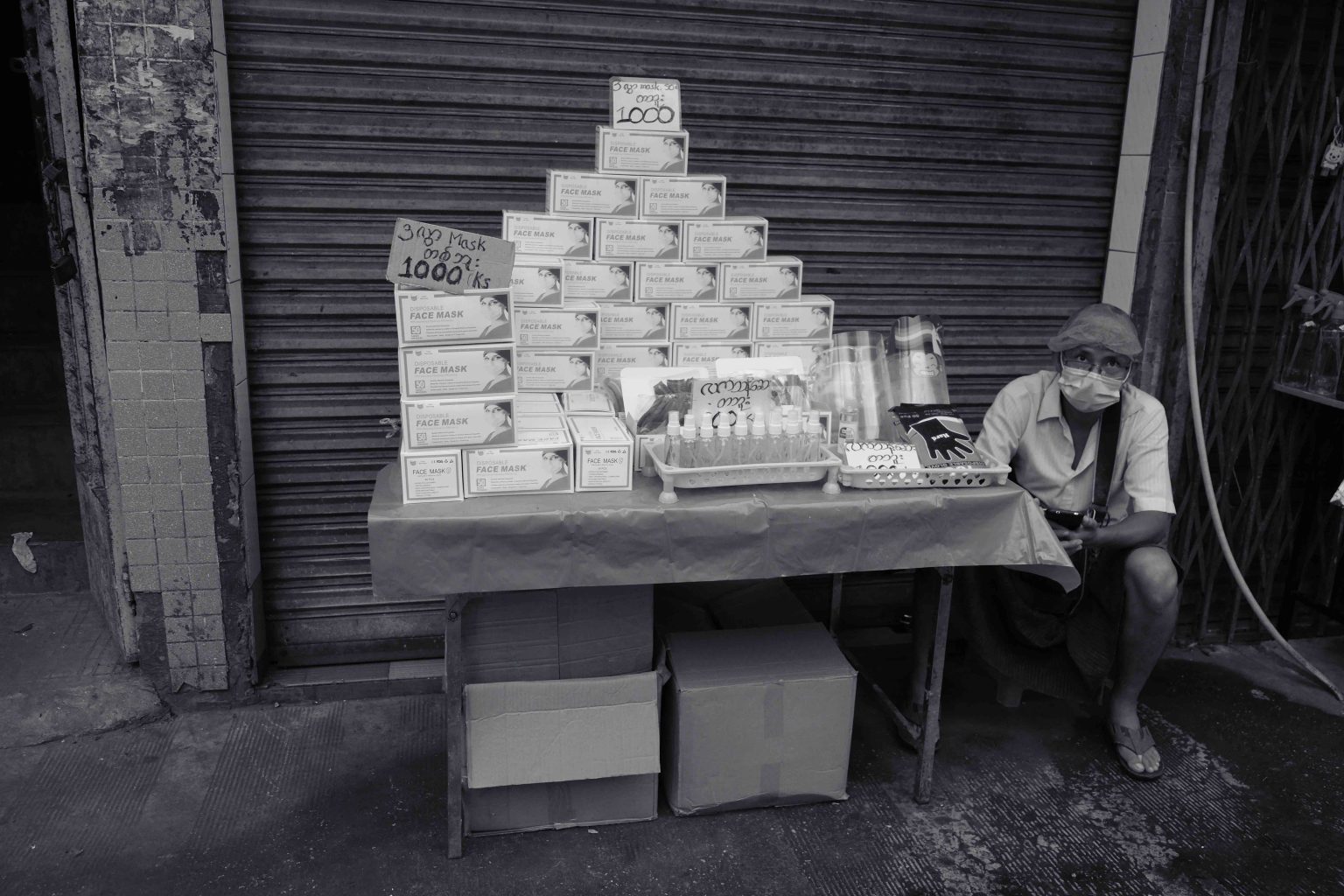

A man selling masks, face shields, gloves and hand sanitizers on Mahabandula Street. With the lockdown, many street venders quickly switched from selling fruits or flowers to personal protective equipment.

Bean cakes for sale at a teashop in Yangon’s Chinatown. Teashops, they city’s iconic and most frequented community spaces, were ordered to close in early September indefinitely after reopening just two months earlier following the first lockdown. Small local businesses have been hit hardest. Many had no choice but to permanently close.

Children play on a barricaded street while a nun collects alms, wearing gloves, a facemask and a plastic face shield. Monasteries and nunneries, factories, old people’s homes and prisons, struggle the most to contain the spread of the virus. With monks receiving more support, nuns are unable to gather enough alms and face serious food shortages.

Young men enjoying a game of caneball on Bogyoke Aung San road, one of the city’s main arteries. As lockdown drags on, tired residents begin to venture out and make use of the quieter streets. Older men bring out chairs, share tea and chat in the early morning and evening hours, discussing friends who receive oxygen and neighbours who have died from ‘the disease’.

An elderly street vendor, resting atop her packed-up goods on deserted Bogyoke Aung San road.

A woman and her grandchildren hawk fresh fish on 37th street. When buses stopped circulating and streets were closed off, many peddlers, unable to afford staying at home, struggled to reach their customers. Yangon’s markets remain hotspots for the virus and many home-bound residents rely on peddlers for fresh vegetables and meat.

A woman selling fish in a usually busy market area in Yangon’s Chinatown.

An upmarket teahouse set up chairs to comply with social distancing rules for customers waiting for their take-away orders.

A candidate of the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) poses in front of an election campaign poster as young volunteers pass by in an open truck, wearing personal protective equipment. The country’s quarantine centres, make-shift Covid 19 hospitals, morgues and cemeteries rely on large numbers of community volunteers.

A young woman walks her cat in a nearby park — a parting gift from her fiancé, a seaman.

Nurses from a nearby hospital take a break from duty at Botahtaung Jetty, near Botahtaung Pagoda, one of the city’s most sacred Buddhist shrines. Temples, mosques and churches have been closed to worshippers since April 2020.

A food delivery boy cycles along Anarawtha road near Sule Pagoda in the late afternoon, normally one of the city’s busiest intersections.

A child sleeps on Pansodan Bridge, near Yangon Central Train Station. A government poster encourages citizens to vote in the November 8 election.

Polina Polianskaja is a social anthropologist and independent researcher, based in Myanmar and its border regions since 2009. Polina has studied women’s lives, displacement and rural livelihoods, women’s access to justice and the law. Born in in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Polina emigrated to Europe after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. She studied languages at the Sorbonne University in Paris and sociocultural anthropology at the University of Vienna and is currently pursuing doctoral studies in social anthropology at the Australian National University (ANU).