COVID-19 is more than just a health crisis. It has accelerated the shift to a digital economy/society, revealed the shaky foundation of international cooperation, escalated hegemonic rivalry between the two major powers, and shed light on the variation of the capacity and nature of states. The Philippine State seems to have shown its true colors as well.

Philippines’ trajectory

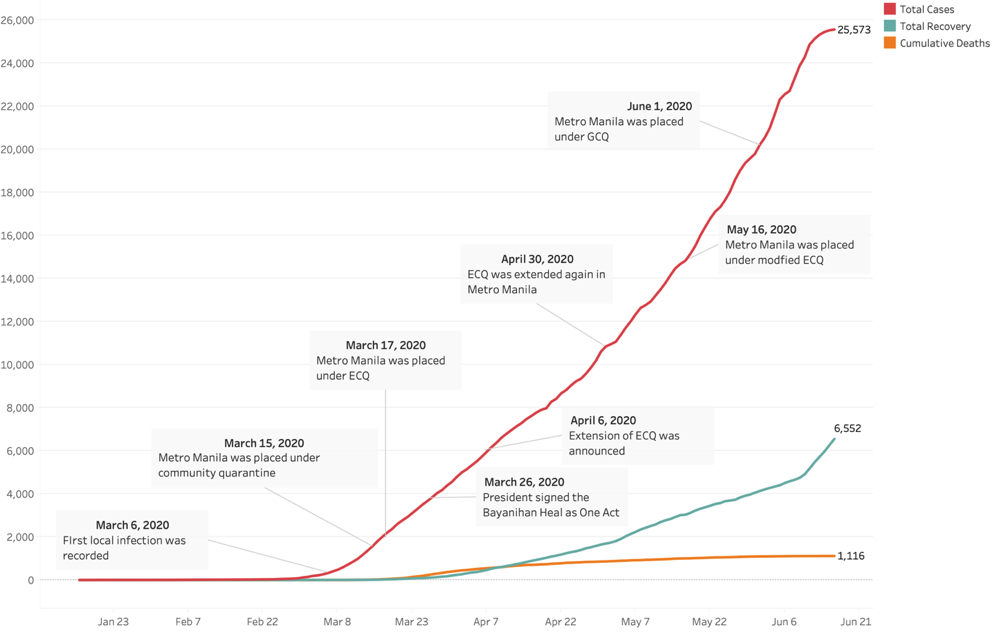

As of 19 June, Philippines recorded 28,459 cases, 7,378 recoveries and 1,130 deaths (DOH, 19 June, 2020). While frequent modifications and discrepancies of these figures often cause confusion and controversy over the accuracy of statistics, it is safe to say that Philippines has been able to avoid the serious outbreak of the likes seen in Europe or North and South America. As the testing capacity and number of beds expanded, daily increase in deaths has become much slower, while recovery rate exponentially picked up over the past two weeks or so. However, the rate of increase of the cases has not been flattened to date.

COVID-19 Cases, Recoveries and Deaths in the Philippines, January 16 – June 16, 2020. Source: Department of Health, Updates on Novel Coronavirus Disease (VOCID-19). https://www.doh.gov.ph/2019-nCoV (last referred on 20 June, 2020)1

The continued increase in the cases is quite puzzling given the hard lockdown in the past months. Philippines had the first case on 30 January, 2020, and first death on February 1. However, both cases were Chinese citizens who traveled from Wuhan, and the cases in the following month were of Filipinos with a history of travel. It was on 6 March that the government recorded the first local infection. As a response to this, the President Rodrigo Duterte placed Metro Manila under General Community Quarantine (GCQ) on 15 March, which caused massive movement of people out of Metro Manila to other parts of the country. Two days later, with the cases increasing rapidly, the President placed the entire Luzon under the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ). ECQ restrict the movement of people except for essential businesses and services such as food, health and finance. Public transportation systems, schools and workplaces were closed, with businesses and government offices urged to have their staff work from home (WFH). Subsequently, on 15 May, Metro Manila was placed under a Modified ECQ (MECQ). Under this classification, selected economic sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, among others, were allowed to re-open with restrictions on the proportion of the workforce who physically report to work.

Economic impact and government’s response

More than two weeks have passed since Metro Manila shifted from a two-and-half month-long ECQ and MECQ to a General Community Quarantine (GCQ). Malls and other business establishments were allowed to operate and some local public transportation resumed with limited passenger capacity. However, the economy looks slow. The light rail transits (LRTs) are running with many empty seats except during peak hours. Traffic is light and the air in the city remains relatively breathable.

It is not just because of the new practices such as WFH. According to the Philippines Statistics Authority, the country’s GDP for the 1st quarter contracted by 0.2%, and unemployment rate hit the record-high at 17.7% with 7.3 million workers unemployed (PSA, 7 May, 2020). Major businesses experience severe year-on-year drops in net profit – 91% drop for San Miguel Corp. (San Miguel Corporation, 2020) and 17% dip for Ayala Corp., to name a few (Ayala Corporation, 2020).

While many other Asian countries are taking steps to reopen their economies, the Philippine government seems to be reluctant, or reserved at best, in its response to COVID-19 and the social and economic impact it has brought. On 15 June, the government decided to extend the GCQ for Metro Manila. A week before the announcement, the Senate failed to enact the Philippine Economic Stimulus Act and COVID-19 Unemployment Reduction Economic Stimulus Act worth P1.3 trillion (US$ 26 billion) and P1.5 trillion pesos (US$ 30 billion) respectively. The two acts had been passed in the House of Representatives to mitigate the economic impact of the stringent lock-down.

However, the Finance Secretary warned that the legislations would double the country’s budget deficit, which accounts for 8.4% of the GDP, and thus violate an alleged constitutionally stipulated limit (Inquirer Net, 8 June, 2020). To date, the fiscal response by the Philippines government under the Philippine Program for Recovery with Equity and Solidarity (PH-Progreso) which is worth P1.74 trillion (US$ 34.8 billion) – is about half of the neighbors’ COVID-war fiscal packages: 73.3 billion in Malaysia, 72.1 billion in Indonesia and 64.76 billion in Thailand (all in US$).

Inadequate state capacity

Moreover, episodes of inadequate state capacity are abundant. The distribution of the P5,000-8,000 subsidy for 18 million low-income households in the informal sector (widely known as Social Amelioration Program or SAP; totaling to P205 billion/US$ 4.1billion) was not completed even two months after it was implemented, mainly due to the lack of comprehensive list of potential beneficiaries. In a desperate attempt to identify the beneficiaries, the Department of Social Welfare and Development sent an SMS to mobile phone users asking ‘Ikaw ba (ay) benepisyaryo ng SAP? (Are you a beneficiary of SAP?).’ Where there is a list of beneficiaries, there are also grudges as the criteria of distribution is not necessarily clear, and some point to a purported unreasonable quota of beneficiaries per barangay despite a higher number of qualified SAP recipients.

With the limited state capacity, the lives of the people in the informal sector depends on the goodwill of their family, friends and employers. City governments have been playing a vital role in supporting the communities, but the provision can be extremely different depending on where you live: two cans of sardine, one boiled egg, and banana in one metropolitan city versus cash aid of P5,000 per registered voters in another city.

In his speech on the eve of the introduction of the ECQ, President Duterte asked the private sector, more specifically big businesses, for help in the areas of food production, income security of the workers, moratorium or waiver of rentals and utility bills (PCOO, 16 March , 2020).

Private sector providing public goods

In response, big businesses such as San Miguel, Ayala, MVP Group of Companies, SM Group, Aboitiz Inc., Gokongwei Group and others, have been playing active roles in the anti-COVID response. Aside from ensuring the full salary and early release of the 13th or 14th month pay for their employees, they continued payments to third-party providers and vendors, and workers in stalled construction projects. They also supported medical frontliners and uniformed personnel at checkpoints through donation and provision of equipment and vehicles, PPEs, free food, and shelter. Property giants waived rental fees, utility providers gave moratorium on bills. Companies also built up a number of testing facilities and converted stadiums and trade centers into quarantine centers, installing beds and partitions, and securing the provision of medical goods, electricity and Wi-Fi connection.

The behavior of big businesses goes beyond what the private sector is expected to do, especially if one considers the role of the sector in other countries, Japan included. San Miguel, for instance, earmarked P13.08 billion ($US 261.6 million) for COVID-19 response by late May. This includes early payment of tax and concessions to the government; continued salary for their own employees and third parties; provision of 70% Ethyl Alcohol to local governments, hospitals and checkpoints; toll waiver for medical frontliners; the building of quarantine facilities and the sharing of their electricity costs; and the continued procurement from local producers and free distribution of food to affected communities among others. In addition to this, the company at a very early stage, promised a stable supply of food products in the country and built its own testing facility for the workers.

Apparatus of violence, limited space and bleak outlook

While the private sector plays an active role in public health, income security, the provisioning of food and medical goods, and boosting the local economy – all of which are supposed to be the function of the government – one of the aspects of the state became overtly visible: the apparatus of violence.

On 13 March, on the eve of the GCQ, President Duterte appeared on TV with the heads of the police and military seating next to him, and repeatedly told the citizens to obey orders from both institutions. While the mere presence of uniformed personnel along the checkpoints was intimidating enough, the President gave an order to the police, military and barangay officials to shoot those who defy the quarantine measure. This came as his response to a group of protesters in Quezon city who resented the lack of relief goods distribution.

The latest episode of the state exhibiting its coercive power was at the peaceful demonstrations against the Anti-Terrorism Act 2020 on 12 June, the Philippine Independence Day. The law provides broad and vague definitions of terrorism and authorizes the arrest and detention of suspects for maximum 24 days without warrant. Protests took place not only online but in universities in spite of the threat of arrest by the police and possible infection. At one site, a 50-strong police force including SWAT team was deployed against a dozen of protestors.

The path the Philippine Government chose in the health crisis – hard lockdown primarily backed by coercive power – has so far has been able to prevent a devastating outbreak. However, the path seems far from sustainable: it has severely damaged the economy and increased unemployment and poverty. An exit strategy seems to be absent, and school closures continue. Worse still, the space for voice has become narrower and narrower, which hinders government from getting valuable inputs on the reconstruction effort.

In the past two decades, the Philippines enjoyed sustained growth. The post-COVID prospect, however, is bleak.

Protestors at De La Salle University urging for #Junk Terror Bill Now.

Deployed police force outside of De La Salle University Campus.

23 June, 2020

References

- Ayala Corporation, “1Q2020 Analyst’s Briefing,” 13 May, 2020. https://www.ayala.com.ph/sites/default/files/05-13-20%20AC%201Q20%20Briefing%20Presentation%20vF_clean.pdf (accessed 20 June, 2020)

- Department of Health (DOH), DOH COVID-19 Bulletin #97, 19 June, 2020.https://www.facebook.com/OfficialDOHgov/photos/pcb.3422036691140892/3422033814474513/ (accessed on June 20, 2020)

- Inquirer Net, “Dominzuez on Congress’ trillion-peso stimulus plans: No funds for that,” June 8, 2020. https://business.inquirer.net/299449/dominguez-on-congress-trillion-peso-stimulus-plans-no-funds-for-that (accessed on 20 June, 2020)

- San Miguel Corporation, “Investors’ Briefing: 2020 First Quarter Results,” 28 May, 2020. https://www.sanmiguel.com.ph/files/reports/IR_Briefing_1Q2020_-_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 June, 2020)

- Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO), “Guidance of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte on the Coronavirus Disease 2019,” 16 March, 2020. https://pcoo.gov.ph/presidential-speech/guidance-of-president-rodrigo-roa-duterte-on-the-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/

- Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA), “GDP declines by 0.2 percent in the first quarter of 2020,” and “Employment Situation in April 2020,” both released on 7 May, 2020. http://www.psa.gov.ph/national-accounts; http://www.psa.gov.ph/content/employment-situation-april-2020 (accessed on 20 June, 2020)

Note

- 1 Due to delays in reporting, the following figures may be incomplete: Cases, June 4 onwards; Recoveries, June 7 onwards; Deaths, 30 May onwards. In addition to these figures, readers should note that the accuracy of the statistics has been debated.

Ayame Suzuki is Professor of Faculty of Law, Doshisha University. She is currently a Visiting Professor at the Department of Political Science, College of Liberal Arts, De La Salle University.

Profesor Ayame Suzuki, Source: Author

Citation

Ayame Suzuki. 2020. “Philippines Response to COVID-19: Limits of State Capacity” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.