Thailand’s History of Authoritarianism

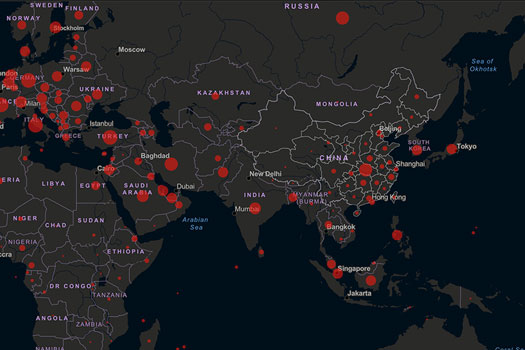

In Thailand, 2020 will be remembered more for COVID-19 than for the State of Emergency which authorities decreed ostensibly to combat the virus. But Thailand’s 2020 draconian response to COVID-19 has re-illuminated the authoritarian character of the current regime governing the country and the absolutist heritage of the kingdom itself. In Thailand, the monarchy, military or a partnership between them has always succeeded in dominating the country. Such is the political plague which has bedeviled attempts to achieve democratic progress. Five times in Thai history the two have collaborated to topple elected civilian governments: 1947, 1976, 1991, 2006, and 20142. Centuries of monarchical absolutism left a lasting legacy of enormous military influence, with an endless array of military strongmen—a supply that continues until today. Staging putsches has been a habitual pastime for Thai military officials, with 14 overt coups since the 1932 putsch against the palace. Various internal or external crises have contributed to military leaders demanding more defense budgeting or authority—and almost always getting it. Meanwhile foreign financial aid to the armed forces has helped to beef up Thailand’s military might. That being said, the military could be considered strong when it is least factionalized simultaneous to when civilians are relatively divided.

With elected civilian-led governments existing sporadically in Thailand for 25 out of the last 88 years, but always punctuated by military coups, civilian control over the military has tended to be absent or frail at best. As a result, military-committed human rights abuses, legal impunity for soldiers and corruption in the military have been common. Though the military continues to be a leading political player, since 1980 it has remained junior partner to the monarchy since the military derives its legitimacy from being a guardian of the palace as a “monarchized” military (Chambers and Waitoolkiat, 2016). With five exceptions, the monarchy has endorsed all 14 post-1932 putsches.

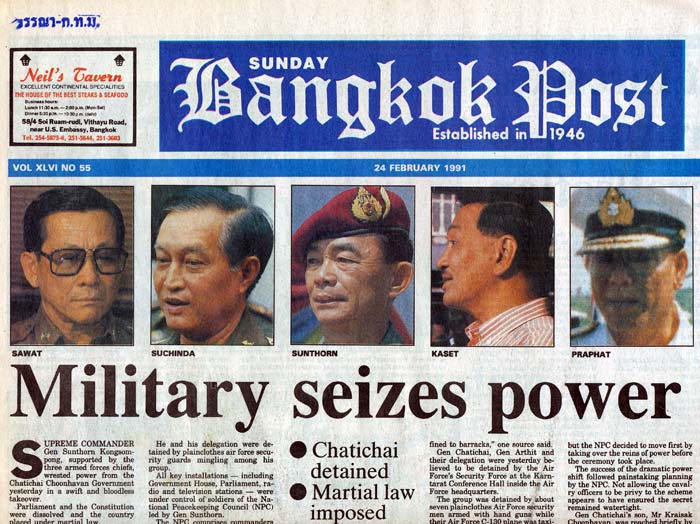

Bangkok Post announces the February 23, 1991 coup whose chief instigators were Army Commander Gen. Suchinda Kraprayoon (second from left) and Supreme Commander Gen. Sunthorn Kongsompong (center). The latter is the father of 2018-2020 Army Commander Apirat Kongsompong. Source: 2Bangkok.com http://2bangkok.com/09-1991coupheadlines.html.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2006 coup, Gen. Sonthi Boonyaratklin appeared on television to announce its completion, advertising royal support. Photo credited to RTE News, Ireland

The palace-endorsed 2014 coup produced five years of military rule during which several regulations were imposed. This included a 2017 constitution (whose writers the junta had appointed), which placed limits on any future democracy, such as making the Senate 100 percent junta-appointed. Thereupon the junta oversaw and enforced a 2019 election which was a complete farce. The junta used intimidation, gerrymandering, post-election recalculating of the electoral formula and controls over media to help Palang Pracharat, the party it had created, achieve victory. Not surprisingly, the Election Commission, whose heads the junta had also appointed, endorsed Palang Pracharat as the election winner. This allowed junta leaders to change their form of control from junta to party, and the party’s candidate, ex-junta leader Prayuth Chan-ocha, to lead a ruling coalition in Thailand’s new façade democracy (iLaw, 2018).

Weaknesses of Thailand’s Regime and Military Leadership in 2020

After 2019 it might have appeared that the military-dominated Palang Pracharat regime and the senior military officials supporting it had succeeded in perpetuating their power far into the future. However, five factors have diminishing their clout.

First, Thailand’s new monarch since 2016, King Rama X, began exercising more direct personalist control over the military and police (relative to his father). This included a) the establishment of direct palace control over the 1st Division, Kings Guard and Royal Guard 904, both of which were absorbed into a newly renamed Royal Command Guard; b) working toward moving all military units outside of Bangkok except for those under the King’s direct control; c) establishing a new Kings’ Guard-dominated base of army operations in eastern Thailand, thus checking the sway of the Eastern Tigers/Queens’s Guard (ET/QG) faction that traditionally dominated the area; d) placing his consort (later Queen) as Commander of the Special Operations Unit of the King’s Guard; e) restocking the Privy Council with retired senior officers loyal to the new King; and f) directly influencing the selection of military and police commanders.

Second, intensifying army factionalism has increasingly diminished military unity. From 2007 until 2016, the ET/QG faction dominated the army. As a result, ET/QG leaders Gens. Prawit Wongsuwan, Anupong Paochinda and Prayuth Chan-ocha achieved political prominence and ET/QG offices successively served as Army Commander. However, there was growing frustration in the army as soldiers belonging to other factions tended to lose out in promotions. With the ascension of a new king in 2016, the palace endorsed the posting of a new Army Commander from Special Forces faction. He was succeeded by the current Army Chief Gen. Apirat Kongsompong, from the Wongthewan army faction. Wongthewan is favored by the King, and with Apirat’s retirement in October 2020, his successors will be either of two Wongthewan officers (Gen. Natapol Nakpanit or Gen. Narongphan Jitkaewthae), stretching Wongthewan leadership over army command into the future. ET/QG’s loss of factional power has diminished the army clout of Prayuth and Deputy Prime Minister Prawit, while greatly lessening military cohesion. Moreover, in 2020 there are four principal factions vying for power in the army instead of one.

Third, there has simply been enhanced civilian exhaustion with a military which has ruled Thailand directly or indirectly since 2014. Discounting the fact that 2019 saw a cosmetic change from junta to party-led governance, the three (military) “musketeers” Prayuth, Prawit and Anupong are still holding on to power in top positions and they have thus been doing so for six years. But ruling through force and/or constitutional manipulation has its limits. The few Thai regimes that have lasted for six years or more have faced mass popular opposition and all were forced to step down from power. The growing number of Thais clamoring for regime change led to the 2014-2019 junta’s holding of the farcical 2019 election. But the election simply allowed popular frustration to become reflected in the newly elected Lower House of parliament with opposition parties demanding a smaller military and more democracy.

On 22 May, 2014, Army Commander Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha (center) announced a coup on television which toppled Thai democracy leading to a 2014-2019 military dictatorship followed by a quasi-democracy (2019-Present). Photo credited to BBC.

Fourth, there has been growing civilian outrage against revelations of military privileges, abuses and corruption while advocates of military reform are punished. The abuses have included a land scandal involving Prayuth (Khaosod, 2014), luxury watch disclosures implicating Prawit (Bangkok Post, 2018), and the involvement of Captain Thammanat Prompao in conspiring to import heroin to Australia (Ruffles and Evans, 2019). In February 2020, the three escaped censure in parliament only a week apart from the junta-appointed Constitutional Court’s disbanding of the Future Forward Party (FFP). The court ruled that FFP had violated a minute technicality within the new junta-endorsed party law (Peck, 2020). FFP was destroyed most probably because its progressive and well-liked leader Thanatorn Juangroongruangkit espoused a popular platform of placing limits on military power and widening political space in Thailand. Earlier that same February, a massacre of civilians committed by an army official revealed that he had lost money in a shady military business scheme. The incident shined light on the enormous network of military enterprises which have remained opaque and unaccountable to outside scrutiny. With the military’s image tarnished, the army commander publicly promised reforms (Nanuam, 2020). However, the promises remain overshadowed by the litany of abuses.

Finally, the military-dominated Palang Pracharat regime is likely to become increasingly unpopular given that the Spring 2020 outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic and concurrent economic downturn occurred “on Prayuth’s watch.” The regime’s slow response to the Coronavirus pandemic—which by 1 May, 2020, had grown to 2,954 cases nationwide (WHO, 30 April, 2020)—did little to help its already declining popularity. At the same time, according to the Asian Development Bank, Thailand’s economy in 2020 was “expected to remain sluggish in the near term. GDP growth [was] projected to slow to -4.8% in 2020” (ADB, 2020). With suicides on the rise, Thailand’s Coronavirus-fed economic woes seemed sure to accelerate opposition to his regime.

Thailand’s Autocratic Response to COVID-19

Nevertheless, the Spring 2020 Coronavirus pandemic shifted public attention away from Thailand’s democratic deficiencies while offering the Prayuth government a convenient reprieve from semi-parliamentary rule—a system which had made the regime weaker. Though tighter state controls were perhaps necessary to deal with the virus, the pandemic temporarily rationalized the government’s 25 March declaration of a state of emergency through which the military could temporarily resurrect its pre-2019 autocracy. Applying the 2005 Emergency Decree on Public Administration in a State of Emergency, the regime forthwith prohibited “rallies…or activities inciting unrest,” forbade the dissemination of information that it considered “not true” or the “intentional distortion of information,” and established long periods of daily curfew (Royal Thai Government, 2020). Those violating these orders could be imprisoned for up to five years under the Computer Crimes Act or the Emergency Decree, following guidelines from the regime’s newly created Anti-Fake News Center. The Decree also gave provincial governors total control over their provinces, and permitted the military to support the police in enforcing emergency regulations (Ibid). In the end, COVID-19 has given the regime extra time to rule by decree before having to confront parliamentary opposition again.

Security officials enforce Thailand’s State of Emergency, which took effect on 25 March, 2020 in response to the advent of Coronavirus. Photo credited to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Thailand’s Political Future

What then are the future scenarios of Thai democracy? Once the Coronavirus plague dissipates, the Prayuth regime will eventually be compelled to withdraw the State of Emergency. The first scenario argues that Thai people, focused on post-COVID-19 economic problems, will give little priority to political change, and thus permit a return to the state quo ante of façade democracy. But popular dissatisfaction with a regime overseeing defective economic and political conditions would remain just around the corner.

In the second scenario, an unpopular Prayuth regime will likely be forced to contend with growing resistance within parliament and in the streets. However, parliamentary opponents to the regime remain themselves disunited. Moreover, any protests and parliamentary opposition could at some point lead to the regime’s re-application of unpopular, military-enforced authoritarian rule, as happened in 1958 and more overtly in 1971.

This gets us to the third scenario. If rising discontent against the Prayuth regime pushes it to seek the return of authoritarian rule, it would have to order the Army Commander to enforce martial law. However, with the current Commander belonging to the Wongthewan faction rather than Prayuth’s ET/QG clique and answering to the King alone, there is no certainty that he would follow Prayuth’s orders. The current king is himself unpopular, has in the past identified himself with military strongmen and spends most of his time abroad. With the monarch seemingly disinterested or distracted, he is unlikely to push for democratization in Thailand—although he might permit a coup by the Army Commander against the Prayuth regime à la 1957.

In the fourth scenario, only largescale, united and long-term public discontent leading to demonstrations—if these are not repressed by the military– might produce meager political change. This includes either the (merely cosmetic) formation of a new coalition (involving Palang Pracharat) headed by a new Prime Minister or possibly (though not likely) a new election.

Conclusion

The Coronavirus pandemic has offered Thailand’s ruling regime an excuse for at least temporarily reasserting direct rule. The sad reality in 2020 Thailand is that it remains mired in an historical tragedy of authoritarianism. Despite its weaknesses, the partnership between monarchy and military—with the latter as junior partner, still dominates the country. It is ironic that this remains the case given that Thai civil society (NGOs) seems to have deep roots (relative to other countries in mainland Southeast Asia) while most Thais do value democratically-elected and civilian-led political parties such as Thaksin Shinawatra’s Pheu Thai. But there is a great divide among NGOs and parties over the issue of Thaksin. Meanwhile parties themselves are either factionalized or have been victimized by judicial dissolutions. Finally, many urban (mostly Bangkok-based) middle to upper class Thais are apathetic to the plight of Thailand’s rural poor majority. Until divisions among Thai people are replaced with a cohesive front demanding constitutional change, elected civilian control and an end to the unaccountable monopoly on power by Thailand’s topmost aristocratic interests, then we are unlikely to see changes in Thailand’s cycle of coup-autocracy-façade democracy-coup. But exactly how will Thailand overcome authoritarian actors to widen political space? Who will lead Thailand toward effective democratization? At this point, there are no answers to these questions. As with most of Thai contemporary history, the country’s path toward a political awakening remains dark, hindered by traditional institutions and societal disunity, and thus successfully stalled.

12 May, 2020

References

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2020. Economic Indicators for Thailand. https://www.adb.org/countries/thailand/economy. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Bangkok Post. 2018. Regime Critics Slam Decision in Prawit Watches Case. 28 December 2020, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/politics/1602434/regime-critics-slam-decision-in-prawit-watches-case. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Camus, Albert. 2013. The Plague. London: Penguin Modern Classics.

- Chambers, Paul. and Waitoolkiat, Napisa. 2016. The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand. In Journal of Contemporary Asia, Special Issue, 23 March, Volume 46, Issue 3, pp. 425-444. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00472336.2016.1161060?src=recsys. (Accessed 2 May 2020)

- iLaw. 2018. The 2019 Elections, of the NCPO, by the NCPO, and for the NCPO. 7 November 2020. https://ilaw.or.th/node/5004. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Khaosod. 2014. Prayuth Deflects Questions about 600 Million Baht Land Sale. 4 November, 2014. https://www.khaosodenglish.com/politics/2014/11/04/1415098178/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Nanuam, Wassana. 2020. Mall Massacre Sparks Army Rejig. Bangkok Post. 16 February, 2020. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/1858409/mall-massacre-sparks-army-rejig (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Peck, Grant. 2020. Court in Thailand orders Popular Opposition Party Dissolved. ABC News (Associated Press), 21 February, 2020 https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/thai-court-orders-popular-opposition-party-dissolved-69120382. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Royal Thai Government. 2020. Requirements issued according to Article 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations (2005), (Version 1). Royal Gazette, Volume 136, Issue 69, p.10 (in Thai) 25 March, 2020. http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2563/E/069/T_0010.PDF. (Accessed 2 May 2020)

- Ruffles, Michael, Evans, Michael. 2019. From sinister to minister: politician’s drug trafficking jail time revealed. The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 September, 2020. https://www.smh.com.au/national/from-sinister-to-minister-politician-s-drug-trafficking-jail-time-revealed-20190906-p52opz.html (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2020, WHO Thailand Situation Report: Thailand Situation in the Last 24 Hours. 30 April, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/thailand/2020-04-30-tha-sitrep-68-covid19.pdf?sfvrsn=6201c7d4_2. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

Notes

- 1 The Plague, written by Albert Camus in 1947, tells the story of a raging epidemic in Oran, a city in French Algeria. The book examines the nature of the human condition and destiny. (Camus, 2013).

- 2 In 1948, military leaders (without support from the palace) ousted elected civilian Prime Minister Khuang Aphaiwong.

Paul Chambers is Lecturer and Special Advisor on International Affairs at the Center of ASEAN Community Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand. At the time of writing he was a Visiting Research Scholar at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, Japan.

Citation

Paul Chambers. 2020. “Political Plague: Thailand’s COVID-19 State of Emergency as a Mere Footnote in an Historical Tragedy of Authoritarianism” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.