Abstract

The fourth wave of Covid-19 pandemic (27 April to October 2021) had a large impact on Vietnam and forced Hanoi to apply social distancing and lockdown directives. This affected many students and young people, particularly low-skilled laborers belonging to ethnic minority communities living and working in Hanoi. These groups faced four barriers: structural, economic, cognitive, and psychological. This brief research paper based on interviews with 15 ethnic minority youths, identifies the difficulties they encountered and examines their relationships within their social networks and their ability to overcome obstacles.

Introduction

The International Organization of Migration (IOM) has defined a migrant as “a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently” (IOM, 2019). For such groups, social networks, formed by individuals or organizations in which people are often connected through interdependent ties, help foster social capital and reduce unpredictable/uncontrollable risks due to lack of information and economic and psychological “costs” they sometimes bear as seen with those who have faced recent Ebola or HIV/AIDS epidemics (Trapido 2019, Đặng Nguyên, 1998).

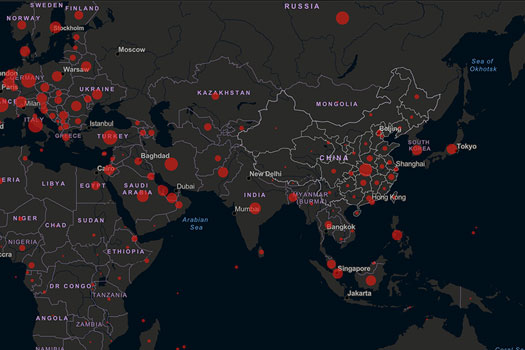

Since the global outbreak of COVID-19, many reports have pointed out the problems different groups have faced. Some have suggested that community interactions reduced feelings of loneliness during the pandemic (Hailey et al 2021), thereby increasing physical and mental health, especially for minority groups (Kim 2020). During the pandemic, the International Labor Office (ILO) (2020) paid more attention to the freedoms of disadvantaged youth groups and their rights were seen to be more vulnerable than others. Social networks play an important role for interpersonal group relationships (Wellman 2008). In response to the global Covid-19 pandemic, Vietnam, since the end of January 2020 initiated various lockdowns, however, it still recorded 831,523 new cases during the fourth wave. The country has given around 51.4 million vaccines (23.8 million people have recieved a first one and 13.8 million a second one) up to the beginning of October 2021. Minority groups were heavily affected by the pandemic but there is a lack of research focusing on young immigrants in big urban cities, especially those who have lived through this difficult time. As such there is a need to consider how they have been impacted during the COVID-19 lockdown. My current research aims to clarify a number of questions. Firstly, what barriers have ethnic minority youth in Hanoi faced during social distancing/lockdown? Secondly, how did the social networks of ethnic minority youth play a role in helping this face issues under the lockdown? And finally, how did these barriers impact the resilience of this group?

Considerations and Methodology

This research project utilizes a Healthcare Access Barriers for Vulnerable Populations Model (HABVP) to examine what obstacles ethnic minority groups may face during social lockdown/distancing and how they manage with or without a social network (George et al 2018). To gauge how such groups reacted during the pandemic, I carried out semi-structured in-depth interviews with six immigrant workers and nine students, coming from different ethnic groups (Mong, San Diu, Thai, Nung, Ha Nhi) who stayed in Hanoi during the fourth Covid-19 wave. I provide three case studies (CS 1, 2, 3) that represent three different kinds of youth in Hanoi. I analyzed them not only through interviews, but also through informal discussions over a three-month period.

CS1: S.M.L (20s): Hmong ethnic boy from Ha Giang with hundreds of acquaintances in Hanoi. S.M.L used his personal relationship to raise funds to help many Hmong people who are “stuck” in Hanoi.

CS2: P.K.C (19 years old): Ha Nhi ethnic youth from Son La with about twenty acquaintances in Hanoi (a normal sized group number for this particular group).

CS3: G.S.B (20s) : Hmong ethnic boy from Lao Cai having one friend after 3-4 years working. This friend left before the Covid-19 outbreak in Hanoi; therefore, G.S.B had virtually no acquaintances in Hanoi.

Structural Barriers for Young People

Structural barriers often relate to transportation, geographical location, systems organization, the general availability of services or access to information and health infrastructure (George et al 2018). During the Covid-19 epidemic in Hanoi, many young immigrants had limited access to government support programs and needed to overcome economic deprivation that they faced. Youth mostly had access to information about social support through motel owners. One said the following:

(CS1) “I just ate rice for nearly a week when the innkeeper came and said that we went to the committee to receive 200,000 VND and 10 kilograms of rice. Only then did I know that I was supported, and I was also helped a lot.”

Another noted that:

“We had three people in the motel room together to share money for buying instant noodles. After all, we also received food thanks to the innkeeper who reported the committee.” (23 M, Hmong student)

Those who worked as builders or staff for restaurants and hotels were also greatly affected during the epidemic. Owners in fact, were not greatly aware of what policies they were supported by, but through good will gestures they provided provisions to staff and employees.

“My friend is a builder in Hanoi without any insurance. Due to social distancing, they have received subsidized food and accommodation from employers. However, these people are too poor to support them much longer. They also didn’t know anyone else in Hanoi, therefore, they had to walk about 300km back to their hometown.” (23 M, Hmong student)

(CS3) “I work as a waitress at a hotel, but there were no customers during the epidemic. The owner had to endure many difficulties, so I needed to leave three days before lockdown.”

All those I interviewed had been vaccinated with one or two doses. The only problem that these temporary residents encountered was that they had to make room for local people to receive vaccines even though they had queued earlier. This prioritization of local residents over the ethnic youth caused some young people to lose self-esteem with one remarking, “maybe it’s because we’re ethnic people.” (22 M, low-skilled Hmong worker)

Economic barriers

Access to employment was also one of the biggest obstacles for all persons that were interviewed. Many of them did not want to return to their hometowns for fear of being discriminated against due to spreading the disease; nevertheless, low-skilled laborers, especially breadwinners, staying in the city ended up draining their funds.

“I had a part-time job with a small amount of money saved up. But many friends don’t have enough food. They do not eat enough (three meals a day), and every meal is under 15.000VND. I cannot do anything but buy them little food.” (24 M, Hmong student)

(CS3) “I eat only rice every day. It’s so bad. Whenever I called home, no one would help me. My parents have passed away, I lived with my aunt and uncle who just called me for money before but refused to help me whenever I needed it.

During this difficult time, some ethnic youth (Thai, Hmong, Ha Nhi and Dao) living in the same alley would alternate to be on duty at Covid-19 border gates to gain food. This they did to check individuals travel documents, to make sure everyone is masked and so that strangers do not spread infections in residential areas. In terms of living expenses, some who still had a job would lend money to others. Only two people answered that they had almost no financial difficulties during the epidemic, one of them was a San Diu high-skilled worker (income more than 10 million VND/month) and the other was a Nung student from a well-off family who still receives a regular family allowance. They said that “this time my work is still quite smooth, and the salary has not changed at all” (26 M, San Diu high-skilled labor). Another also noted that “my family allowance is not only enough for my personal expenses, but also for my shopping online needs” (21 F, Nung student).

Cognitive barriers

Cognitive barriers have been shown to be those those that relate to knowledge, communication, language and health literacy (George et al 2018). Ethnic minority students in Hanoi, like all students, must study online. Even though having spent many years of intensive study at a boarding school, CS2, the only undergraduate student interviewed, still found it impossible to socially connect with other classmates (due to not knowing them) or take online lessons. He still has no former friends that he knew before moving to reside in Hanoi. Therefore, he decided to quit university before the second academic semester.

(CS2) “From the first day, I didn’t understand what the teacher was saying and having conversations with classmates is challenging. At first, I worked while studying. Then I stopped studying completely.”

With immigrant workers, only a few who have been in Hanoi for a long time actively register to procure a new social insurance and health insurance at their temporary residences even though some feel that they won’t need it, and some of them don’t care about insurance, As CS3 shared, “If I get sick, I will go to pharmacy instead of the hospital.” They are also not aware of the importance of labor contracts. This is one of the reasons why they have not received appropriate support during the epidemic.

Psychological barriers

Psychological barriers have been shown to correspond to mainly four main subthemes: mistrust, hopelessness, fear and anxiety (George et al 2018). Some ethnic minority students who wanted to find jobs online encountered petty antisocial behavior. One student said that she “also planned to find another part-time job while waiting for the epidemic to pass, but I am afraid…My friends are rejected because they are ethnic people” (21 F, Nung student). A reason for being disqualified may be due to how they perceive their treatment, and this shows that they have a sense of self-esteem when compared to other candidates. A feeling of inferiority also arises when they receive an allowance; “sometimes, if it’s help from the community (in other words the Hmong student community in Hanoi), I feel like it’s just friends sharing with each other, but if it’s from the university/ward of committee, I feel a little shy and indebted” (20 F, student Hmong).

During their stay at home, most people shared a common feeling: that of suffocation. This feeling manifested itself with most people in the lockdown areas in Hanoi, but here I analyze this from the perspective of memoryscapes, that is, re-imagining places. One study in Vietnamese has shown that adjectives such as “hot,” “chaotic,” “bustling” and “dangerous” were those that most frequently appeared in the usage description of ethnic minority youth living and working in Hanoi (iSee 2019). Many of them, as with CS2, from the first day in Hanoi, felt “panic and thought that they would die because there was no oxygen.” These emotions are both implicit in the differences in the physical landscape of rural and urban spaces in general, but at the same time, it reminds them of their identities as “người miền núi” (mountaineers). For example, one Hmong student said that “the first thing I will do after the epidemic is probably go jogging around a lake surrounded by trees and nature, like being at home.” (26 M, Hmong student). These comments above tentatively suggest that young ethnic minorities must confront these four areas within their vulnerable groups. In their reported speech, social relationships may be mentioned directly or indirectly showing the influence of the networks available for analysis. What requires further study is the impact of social media in creating cognitive barriers. During the pandemic, most research subjects came to rely on their mobile phones, with easy access to online newspapers and to a certain degree this exposed them to various types of information include false ones. Here, usage of information access will be significantly reduced (as on an individual level each person handles information related to the epidemic) or it will significantly increase if interactions with information take place strongly within each group and if they are the victims of fake news. This preliminary research suggests more research will be needed on groups of low-skilled workers comprising students whose psychological wellbeing was impacted by isolated during the pandemic

Discussion

One thing that arose from interviews is that financial barriers have acted to motivate, create, and strengthen social networks and these affected them most evidently. CS1 confirmed that everyone who is connected to him expressed that money was the greatest worry they had. Meanwhile, both CS2 and CS3 shared that they were lonely during the lockdown period. They could deal with this loneliness and continued to lie down on their beds “in a quiet room” (CS2) or “wait for time to pass slowly” (CS3). For both informants, what this suggests is that financial, and not psychological barriers were strong enough to motivate young ethnic minority people to construct and maintain their networks. Also, something should be said on the roles of “pre-migration relationships, ” which are important for both students and low-skilled workers. Students, for example, tend to find friends from the same hometown or ethnic group when in need of help when dealing with difficulties such as family, friends, and those in their kinship networks. Workers also relied on relatives or old friends to whom they are close. In other words, strong ties (i.e. ethnic or kin based) that bond can also help overcome psychological barriers. CS2, (a Ha Nhi ethnic minority) said that “the number of Ha Nhi people in Hanoi cannot be counted on the fingers of one hand. None of my friends are studying or working in Hanoi.” When receiving social support or being fired during the epidemic, he thought it was normal and didn’t blame his ethnic identity at all. This attitude helps me assume that the more stable and denser a group (for each ethnic minority), the higher the tendency there is to separate from other groups. It is this regular interaction in the group that continuously reminds them of their identity, and this requires clarification through further research.

One final point I want to make clear is that social network sizes do not seem to influence their resilience. In this brief study, whether young people have hundreds of relationships in Hanoi or less, their close relationships are only at the level of 3 to 5 people (excluding the case of CS3 who had less than 3 relationships in Hanoi). In line with the brief resilience scale (Smith et al 2008), CS1, CS2, CS3 all had the similar normal resilience levels. With connections between social networks and social trust, we can also measure the expectations of trustworthiness of others through a General Trust Scale (Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994). Interviews with informants showed that opposing trends were noticeable such as with those with many in their social networks who are likely be more trusted than those with fewer relationships. In contrast, CS1, for example, has hundreds of relationships in Hanoi, but shows a more obvious lack of trust in people.

Conclusion

The approach used in this study has highlighted the difficulties that ethnic minority youth had to face when deciding to stay in Hanoi during the fourth Covid-19 wave. Diverse, overlapping difficulties showed that they needed timely and essential help from social organizations and government, something that has been lacking. Although the sample pool was small – only 15 young people from several different ethnic groups-, this study suggests we need more research on young ethnic minorities people in urban areas, especially when unpredictable circumstances such as epidemics or natural disasters disrupt their lives.

1 March, 2022

References

- Đặng Nguyên, Anh. 1998. Vai trò của mạng lưới xã hội trong quá trình di cư. [The Role of Social Networks in the Process of Migration] Tạp chí Xã hội học 2(62). Journal of Sociology 2 (62) 16-24. (in Vietnamese)

- George, S., Daniels, K., & Fioratou, E. 2018. A Qualitative Study into the Perceived Barriers of Accessing Healthcare among a Vulnerable Population Involved with a Community Centre in Romania. International journal for Equity in Health, 17(1): 1-13. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-018-0753-9 (Accessed 30 January, 2022)

- IOM. 2019. Glossary on Migration. International Organization for Migration. Switzerland, pp 132-133. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (Accessed 30 January, 2022)

- iSee. (2019). Navigating Opportunities and Challenges: The Case of Urban Young Ethnic Minority Migrants in Northern Vietnam.

- Kim, Joongsub. 2020. The Role of Social Cohesion in Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health within Marginalized Communities. Local Development and Society. 1(2): 205-216. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26883597.2020.1829985 (Accessed 15 January, 2022)

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. 2008. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. International journal of behavioral medicine. 15(3):194-200. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1080%2F10705500802222972 (Accessed 15 January, 2022)

- Trapido, J. 2019. Ebola: Public Trust, Intermediaries, and Rumour in the DR Congo. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 19(5): 449-558. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30044-1 https://www.thelancet.com/article/S1473-3099(19)30044-1/fulltext (Accessed 15 January, 2022)

- V. Hailey, A. Fisher, M. Hamer, and D. Fancourt. 2021. Impact of Social Support, Loneliness and Social Isolation on Sustained Physical Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.04.21252466v1.full (Accessed 15 January, 2022)

- Wellman, Barry. 2008. Review: The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Contemporary Sociology. 37 (3):221–222.

doi:10.1177/009430610803700308. (Accessed 15 January, 2022) - Yamagishi, T., & Yamagishi, M. 1994. Trust and Commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 18:129-166. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02249397 (Accessed 15 January, 2022)

Giang Bui is currently a master’s student at Vietnam Japan University.

Although a literature and linguistics teacher education graduate, she aspires to be a social science researcher and a writer, particularly on the issue of ethnic minorities in Vietnam. This is her first research to open new space in a field of interest.

Citation

Giang Bui. 2021. “Social networks of young ethnic minorities living in Hanoi during the COVID-19 lockdown” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.