Migration in Nepal, and Nepalese Migrant workers in India

Nepal is a land locked country surrounded by India on three sides: the south, east and west, and China to the north. Towards India, there exists a long, open, and porous border, stretching approximately 1,751 km. In addition to the border, both countries also share similar cultural and religious practices. Since 1950, the Indo-Nepal Peace and Friendship Treaty (1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship 1995) has provided Nepalese and Indian nationalities the ability to travel and work across borders and to be treated on par with the native citizens. As such, a cultural, socio-economic, and political relationship between Nepal and India, makes movement between the two countries a unique and complex cross border-migration dynamic.

Nepal has a long history of international labor migration going back nearly 200 years. Migration into India has been recorded since 1885, when Nepalese citizens were officially recruited into the British Indian army (Rathaur 2001). Following the independence of India in 1947, many young Nepalese workers from rural communities saw cross-border migration to India as a better opportunity for employment, finding labor in tea estates, carpentry, and other menial jobs (Kunwar 2018). The migration inflow to India has increased since the 1950s and 1960s due to various factors such as not requiring work permits, easily convertible currency, affordable traveling options, histories of migration within families and villages and cultural affinities. However, what influenced this was close proximity and open borders between both two countries. The Maoist insurgency of 1996-2006 also saw a huge influx of Nepalese to India and other foreign destination countries owing not only to the threat of violence, but also to declining agricultural and economic production (Bohra-Mishra 2011). In destination countries, particularly to Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries and Malaysia, they primarily perform low and demeaning forms of manual labor, which mostly consists of “3D jobs”- Dirty, Difficult and Dangerous (Shrestha. M, 2017).

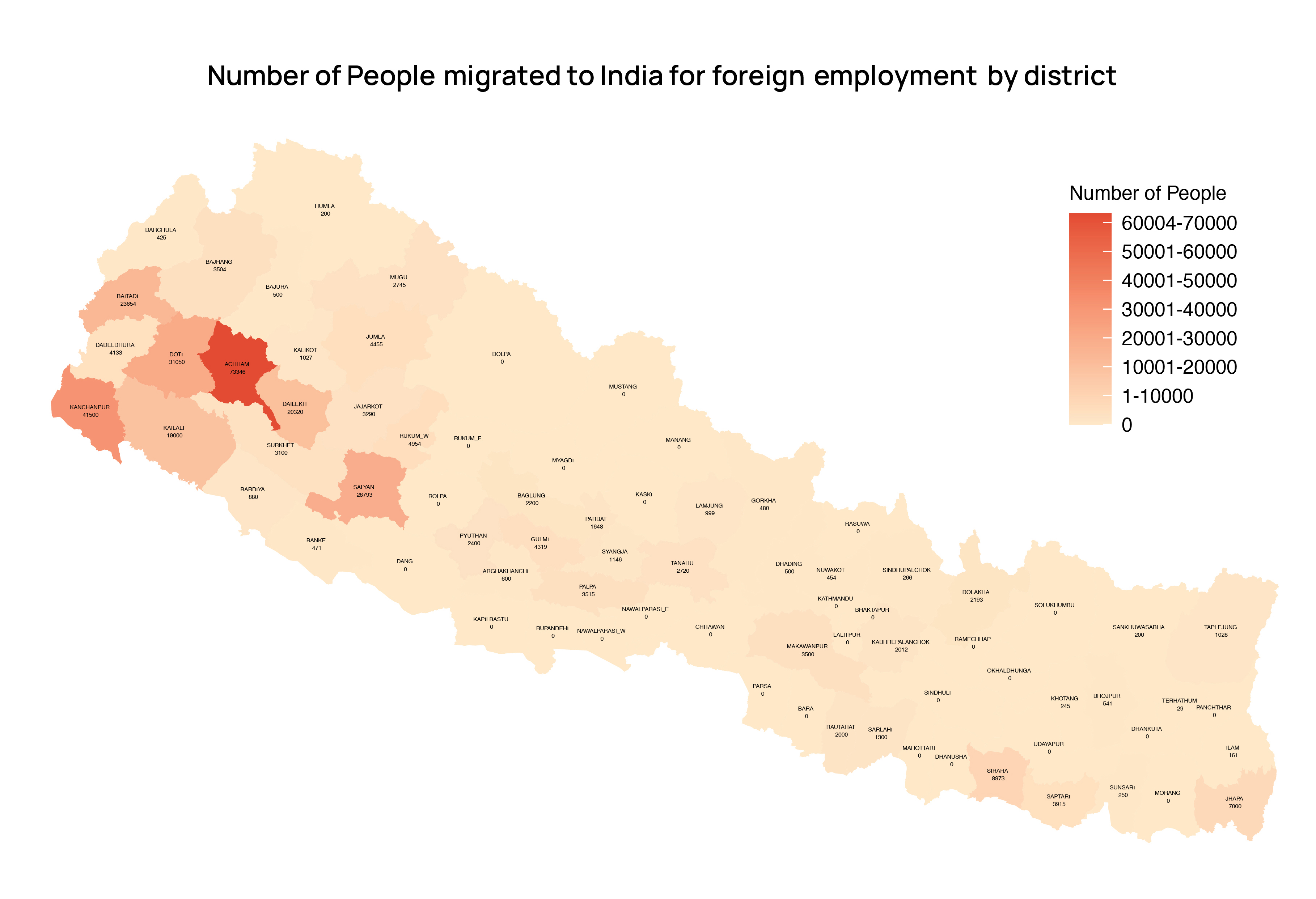

There are no official records of Nepalese citizens working in India as they do not require a labor permit. However, as per the National Labor Force Survey, there are an estimated 587,646 Nepalese migrants in India, most of whom are engaged in the service sector (CBS, ILO 2019). The majority of them are involved in informal and seasonal work (Government of Nepal 2020). A report published by International Labor Organization (ILO) states that approximately 86 per cent of Nepalese migrants in India are daily wage earners in the informal sector, primarily in the agriculture (approx. 26 per cent) and construction sectors (approx. 30 per cent) without any formal employment contracts or other benefits, placing no contractual obligations on their employers to provide them with food, accommodation and health care (ILO [1] 2020). Nepal today stands as the fifth most remittance dependent economy in the world (Gill, The Diplomat 2020) and in 2019 the country received US$ 8.79 billion. A bloody civil war, political uncertainty and devastating earthquake have pushed many young Nepali workers to look for opportunities abroad. Since 2008/09, the government has issued over 4 million labor approvals for 110 countries across the world (DoFE 2020), but migration to India for work still remains to be pivotal for survival and a livelihood strategy for millions of Nepalese.

Source: IOM

COVID-19 and migration situation on the ground (Nepal-India)

The unprecedented outbreak of COVID-19 has brought life to a near standstill in almost every sphere of the world. As the fear of pandemic spread in mid-March, Nepal was one of the first countries in the region to shut down all business, flights, and transport. On 20 March 2020, the government of Nepal imposed a partial lockdown, halting long-distance transportation services, international flights, and non-essential services. Two days later, Nepal declared a nationwide lockdown sealing the international borders for a week from 24 March 2020 following the second case of COVID-19 in the country (The Kathmandu Post 2020 [1]). Nepalese migrant workers from India poured back across the border as India also decided to go on a three-week lockdown from 27 March 2020 to mitigate the transmission of the disease (Nepali Times 2020 [1]). A week before the lockdown in Nepal, approximately half a million Nepalese migrant workers from India had crossed the border into Nepal without any health screening not only because they lost their jobs but mainly of fear of the spread of the disease as cases in India were on the rise (Nepali Times 2020 [2]). Amidst lockdowns in both countries, many Nepalese in India started marching back home either walking back on foot for miles or taking transport only to be stopped at the border and stranded in No-Man’s land (Shrestha, Al-Jazeera 2020). Likewise, hundreds of Indian citizens wishing to return were also stuck at the Nepalese side of the border. Many Nepalese stranded at the Darchula border also risked their lives and crossed the Mahakali river to come back home while many others protested against the government for not letting them enter the country despite a perilous journey, only to be stopped at the border. This put pressure on the government, particularly from human rights bodies and organizations, leading to both governments agreeing on providing basic needs such as food and water to ensure safe quarantine for them as a temporary measure (The Kathmandu Post 2020 [2]).

Jhulaghat Point of Entry during lock down, Dashrathchanda Municipality, Nepal. Source: IOM

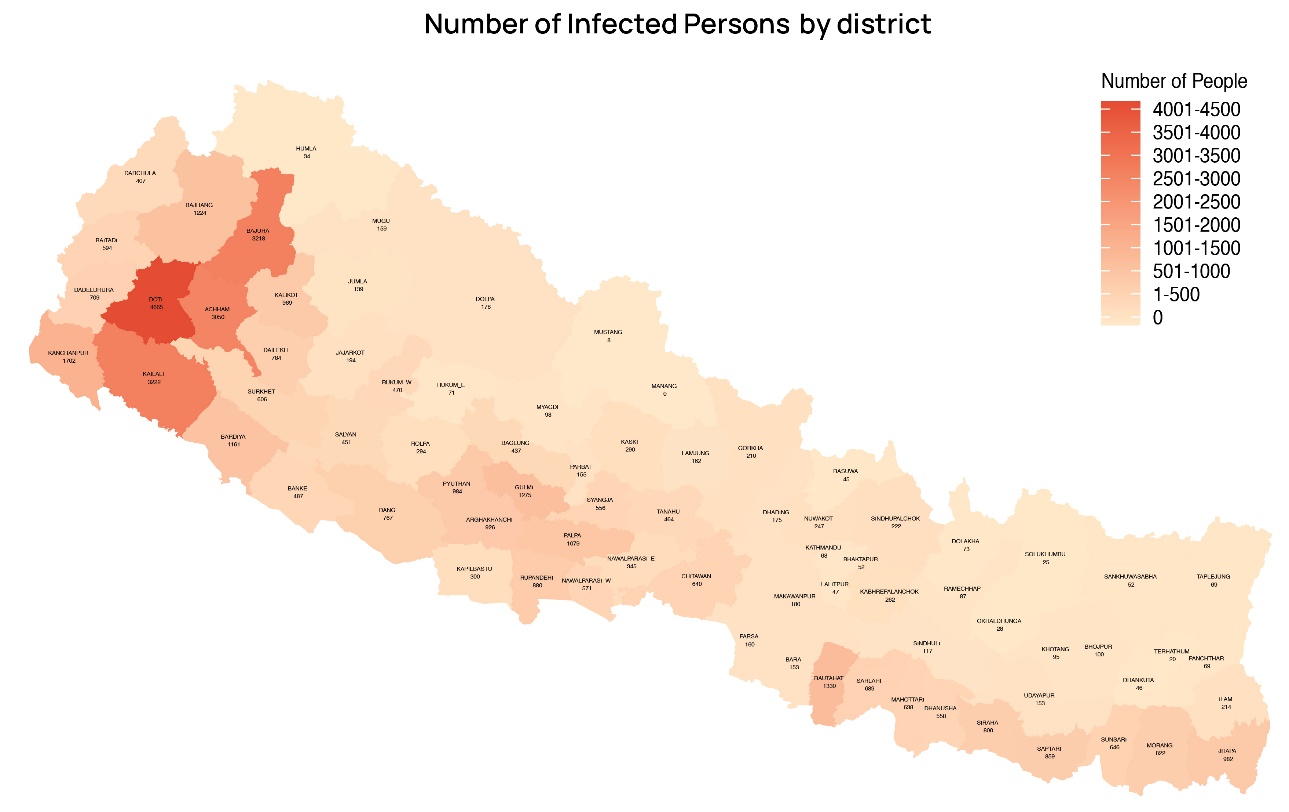

However, the porous nature of the border shared between the two countries led many stranded individuals from both sides of the countries to cross informally and without being detected. In an address to the parliament on 10 June 2020, the Prime Minister (PM) of Nepal, KP Sharma Oli stated that almost 10,000 people were entering Nepal every day. Between mid-April to mid-May, the total number of people entering Nepal from India stood at 7,478, which sharply increased to 222,614 between mid-May to mid-June (My Republica 2020). The preliminary findings of a recent study on “Rapid Assessment on Impacts of COVID-19 on Returnee Migrants and Responses of the Local Governments of Nepal” conducted by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) has revealed that during the study period (23 June – 8 July 2020) out of a total 12,510 confirmed COVID-19 cases, there were 11,377 who had returned from India representing 90 per cent of the confirmed cases at that time (IOM 2020). Local Nepalese government received citizens who had been in Indian quarantine facilities for days, only to send them again to quarantine facilities following entry (Nepali Times 2020 [3]). From only one active COVID-19 positive case detected when lockdown was declared in Nepal, the numbers started steeply rising as citizens began returning back home from India. By mid-June, when the borders saw the crossing of hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and their accompanying family members, high levels of testing were implemented at border provinces. It was noted that 82 per cent of the total cases were reported from Province 2, Province 5 and Karnali Province, all of which border India (WHO Situation Update 2020). Returning migrant workers and their accompanying family members have been placed at quarantine centers and those testing positive have been isolated in border municipalities and districts. However as the pandemic has progressed, even the quarantine facilities established by the local government turned into hotspots as the required standards based on the guidelines by the Federal Government of Nepal were not being met (The Rising Nepal 2020 [1]). The initial one-week lockdown was extended for additional 120 days. With the economic downturn and government revenue sinking, the government decided to lift it on 21 July 2020. However, a further spike in cases as soon as the lockdown was lifted forced the government to re-impose another one in districts across Nepal that had 200+ active cases including the capital city from mid-August. All districts of Province 2 bordering with India witnessed a rapid increase in the number of cases soon after the lockdown was eased due to the free movement of people from the border communities on the Indian side where cases were rising at an alarming rate (The Kathmandu Post 2020 [3]).

As of August 2020, Nepalese returnees have started going back to India for work since major economic activities in Nepal have been severely disrupted due to the month-long lockdown. One border point on the far western part of Nepal mentioned that since mid-July some 1,500 Nepali migrant workers have crossed the border to return to work in India (The Rising Nepal 2020 [2]). With the country already grappling with a beleaguered health system domestically, the added crisis created by COVID-19 is a terrifying reminder of what is to happen next as cases spikes and the number of returnees from India and other labor destinations are on the rise.

Impacts (Health, Socio-economic and Protection)

In Nepal, over 77,000 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed with 498 deaths as of 30 September 2020 (MoHP 2020). Most private health facilities are refusing to admit people with symptoms resembling that of COVID-19 due to their limited capacity to support the treatment of this novel disease and inaccessibility to the health services due to movement restrictions. This has resulted in pre-mature deaths among high-risk populations such as pregnant women and people with co-morbidities (Singh 2020). Similarly, with a rise in unemployment and poverty driven by this crisis, there is a greater chance of food insecurity resulting from malnutrition among children and pregnant women (Singh 2020). Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic response has affected the provisioning of maternal and neonatal health services, reduced institutional childbirth by half during the lockdown, increased institutional stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates, and decreased the quality of care. These are attributable to the heightened fear of acquiring the disease which stopped women from seeking care at health facilities travel restrictions and saturated hospital capacities (Ashish. K.C 2020, Karkee.R 2020).

Source: IOM

There have also been reports of an increasing prevalence of psychological problems among health care workers and the public due to stigma and discrimination related to COVID-19 (Poudel 2020). Many health workers are denied entry into rented houses by landlords due to a fear of infection transmission in neighborhoods (Poudel 2020). Likewise, cases of suicide have also increased following the lockdown in Nepal. According to a report by the Nepal Police, suicide figures have increased by more than 20 per cent compared to before the lockdown (Acharya 2020).

Another dynamic affecting Nepalese migrant workers abroad includes reports of a number of Nepalese migrant workers infected with COVID-19 in various other countries, not being able to receive health care coverage without their legal status, and a concern of discriminatory behavior regarding access to health care. Likewise, migrant workers may be more susceptible to infection due to working and living conditions, which are often overcrowded and unsanitary (ILO [2] 2020). Despite the fear of getting infected, many Nepalese migrant workers abroad were forced to continue their work during the lockdown without proper Personnel Protective Equipment (PPE), making them more vulnerable to the infection (The Kathmandu Post 2020 [4]).

According to a forecast from the World Bank, 31.2 per cent of Nepalese are at risk of falling into extreme poverty due to reduced remittances, the forgone earning of potential migrants, the collapse of the tourist industry, job losses in the informal sectors and an increase cost of essential commodities because of COVID-19 (Sah 2020). Similarly, according to ILO estimates, nearly 3.7 million workers are most at risk to experience a significant reduction in economic output as the result of the COVID-19 crisis (ILO [2] 2020). The same report highlighted that, between 1.6 and 2 million people either will lose their jobs completely or will reduced working hours and wages in the current crisis.

People movement in the Belahiya POE before the pandemic of COVID-19, Siddharthanagar Municipality, Bhairahawa. Source: IOM

National response to the COVID-19 pandemic

To tackle the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government released a “Health Sector Emergency Response Plan,” along with additional guidelines, and directives following the situation. A COVID-19 Crisis Management Center (CCMC) was also formed under the leadership of Deputy Prime-minister, which is driving the main responses to the situation.

Furthermore, the government is preparing to promote a Prime Minister Employment Project (PMEP) as a major source of employment for those who have lost their jobs due to COVID-19 and for returnee migrant workers. This will ensure basic employment opportunities for the jobless. As per a supreme court order on 15 June to repatriate those workers who are unable to pay for their airfares to return home, the government had finalized guidelines for repatriating stranded foreign migrant workers at its own expenses through a Migrant Workers’ Welfare Fund.

IOM, the UN agency for migration in Nepal has provided orientation programs to frontline workers at migrant holding centers on COVID-19, its preventive measures, stigma and stress management. IOM conducted a phone survey to understand the migration related situation, preparedness and response plan for COVID-19. In addition, Population Mobility Mapping (PMM) activities are being conducted in the major point of entries from India within three provinces (Province 1, 5 and Sudurpaschim Province) of Nepal to study the mobility dynamics for better migration management during this time (IOM Situation reports, 2020 [1] [2] [3] [4]). Similarly, IOM has been supporting the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) to conduct an assessment of all ground crossing points from the perspective of International Health Regulation (2005) and the feasibility study to establish health desk prototype envisioned by the MoHP for the screening of returnees from 10 different ground crossing points (MoHP [1] 2020).

Foreseen future and way forward

Despite the lockdown and prohibitory orders, the number of people being infected with COVID-19 is increasing in Nepal leading to speculations of ongoing community transmission. Though the initial “Emergency Health Response Plan: COVID-19” included the estimation of maximum 10,000 positive cases and the plans were made accordingly, it has reached far beyond the projected number (29,000) (MoHP [2] 2020).

The impact of COVID-19 and the ambiguity of the unfolding future has forced Nepalese migrant workers from all over the world, mostly from India to return back to their home country. However, their fate back at home after their return has unfortunately added to anxieties around massive unemployment and an economic crisis to follow. This has pushed them to return back to their destination countries, especially India, even though cases are still increasing. Perhaps in the battle against life and for livelihood, the latter wins as a large number of Nepalis are returning back to India in search of livelihood opportunities across the border as the government continuously fails to provide a solution (The Kathmandu Post [5] 2020). With no social security or health insurance schemes available for Nepalis going to India for work as one gets while going to other destination countries, they are returning back and are forced to take up any job available, in most cases menial jobs, as the Indian economy starts to reopen. The open borders and ease of movement without visa between the two countries also facilitates this decision for daily-wagers, long-term residents, as well as students travelling back to India. Additionally, a limited provision of essential services and discrimination towards repatriated citizens upon return to Nepal have also been key motivators for migration back into India. This is in hope of ensuring food and shelter security for themselves and their families (Rightsview 2020).

The Government of Nepal and other stakeholders should focus on testing, tracing, and treating of individuals with COVID-19 and priority should also be equally given to preventive measures, monitoring of activities, and social protection encompassing vulnerable groups such as migrant women, children, and elderly, individuals with disabilities, and returnee migrants. Furthermore, the stakeholders should also start planning for recovery phase as to response quickly and efficiently when required. Likewise, the government should lay out plans to prepare a long-term solution for the management of the returnee. Rather than providing short term employment through the Prime Minister employment program, it should be focused more on assets building by providing skills and jobs (Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social security 2020). At a local level people should strengthen themselves to implement these kinds of long-term schemes and support those who want to start their own business in the country. This is going to be an overwhelming task, but one that is possible to achieve through consistency, communication, coordination, and corporation among all tiers of government involved.

7 October, 2020

References

- Acharya, Shiva & Moon, Deog & Shin, Yong. 2020. COVID-19 Outbreak and Suicides in Nepal: Urgency of Immediate Action (Preprint). 10.2196/preprints.21754.

- Ashish, K. C., Gurung, R., Kinney, M. V., Sunny, A. K., Moinuddin, M., Basnet, O., … & Lawn, J. E. 2020. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health.

- Bohra-Mishra, P., & Massey, D. S. 2011. Individual decisions to migrate during civil conflict. Demography, 48(2):401–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0016-5

- Central Bureau of Statistis (CBS) International Labour Office (ILO). 2019. Report on the Nepal Labour Force Survey 2017/18.

- Gill, Peter. 2020. Coronavirus Severs Nepal’s Economic Lifeline. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/coronavirus-severs-nepals-economic-lifeline/ (Assessed 28 August, 2020)

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social security. 2020. Nepal Labour Migraton report 2020. https://moless.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Migration-Report-2020-English.pdf (Accessed 30 September, 2020)

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population. 2020. Situation Report # 234. [1] https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1u4WjA4PWgFH_NKlpHhOSCoGKBb6VmLu1 (Accessed 30 September, 2020)

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population. (2020) Health Sector Emergency. [2] Response Plan COVID-19 Pandemic. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Jrg02HTqN-q8KkUESCne35GreQOL199h/view (Accessed 30 September, 2020)

- International Labour Organization 2020. COVID-19 labour market impact in Nepal.[1] https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—ilo-kathmandu/documents/briefingnote/wcms_745439.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- International Labour Organization. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Nepali Migrant Workers: Protecting Nepali Migrant Workers during the Health and Economic Crisis. [2] https://www.ilo.org/kathmandu/whatwedo/publications/WCMS_748917/lang–en/index.htm

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. Returnee Migrants-Focused Rapid Assessment on Impacts of COVID-19 and Preparedness and Response Plan of Local Government. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FINAL_REPORT_IOM.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. IOM Nepal COVID-19 Response Info sheet [1] https://nepal.iom.int/sites/default/files/publication/IOM%20Nepal%20COVID%20Response_May2020.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. IOM Nepal involvement in COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan. Situation Report [2]. June 2020. https://nepal.iom.int/sites/default/files/COVID-19/SitRep_IOM_Nepal_June2020_FinalVersion.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. IOM Nepal involvement in COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan. Situation Report [3] 1-15 July, 2020. https://nepal.iom.int/sites/default/files/COVID-19/SitRep_IOMNepal_1-15July.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. IOM Nepal involvement in COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan. Situation Report [4] 15-31 July, 2020. https://nepal.iom.int/sites/default/files/COVID-19/SitRep_IOM_Nepal_15-31July.pdf (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Karkee R, Morgan A. 10 Aug, 2020. Providing maternal health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. The Lancet Global Health. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30350-8/fulltext (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Kunwar, L. S. 2018. Cross-border migration process of Nepalese people to India. Nepal Population Journal, 18(17):81-90.

- My Republica. 2020. More than 85 percent COVID-19 patients in Nepal are India-returnees: PM Oli. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/more-than-85-percent-covid-19-patients-in-nepal-are-india-returnees-pm-oli/. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Nepali Times 2020 [1]. Nepal and India stop citizens from returning. https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/nepal-and-india-stop-nationals-in-each-others-countries/. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Nepali times. 2020 [2]. Returnees may be taking coronavirus to rural Nepal. https://www.nepalitimes.com/here-now/returnees-may-be-taking-coronavirus-to-rural-nepal/. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Nepali Times. 2020 [3]. Nepalis stranded at India border return. https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/nepalis-stranded-at-india-border-return/. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Poudel K, Subedi P. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socioeconomic and mental health aspects in Nepal. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 10:0020764020942247.

- Rathaur, K. R. S. 2001. British Gurkha recruitment: A historical perspective. Voice of History, 16(2):19-24.

- RightsView, 2020. Stranded in Near Statelessness: The Corornavirus and Nepali Migrants. Columbia University. http://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/rightsviews/2020/09/15/stranded-in-near-statelessness-the-coronavirus-and-nepali-migrant-workers/ (Accessed 1 October, 2020)

- Sah R, Sigdel S, Ozaki A, Kotera Y, Bhandari D, Regmi P, Rabaan AA, Mehta R, Adhikari M, Roy N, Dhama K. 7 Jul, 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Nepal. Journal of Travel Medicine. https://academic.oup.com/jtm/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jtm/taaa105/5868304 (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Shrestha, Subina 2020. Hundreds of Nepalese stuck at India border amid COVID-19 lockdown. Al-Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/hundreds-nepalese-stuck-india-border-covid-19-lockdown-200401031905310.html#:~:text=Nepal-,Hundreds%20of%20Nepalese%20stuck%20at%20India%20border%20amid%20COVID%2D19,to%20prevent%20spread%20of%20coronavirus.&text=Darchula%2C%20Nepal%20%2D%20Ramesh%20Sista%20decided,die%20of%20hunger%20in%20India. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Shrestha, Maheshwor. 2017. Push and pull: A study of international migration from Nepal (English). Policy Research working paper. No. WPS 7965 Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/318581486560991532/Push-and-pull-a-study-of-international-migration-from-Nepal (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- Singh, D. R., Sunuwar, D. R., Adhikari, B., Szabo, S., & Padmadas, S. S. 2020. The perils of COVID-19 in Nepal: Implications for population health and nutritional status. Journal of global health, 10(1):1-4 010378. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010378 (Accessed 1 October, 2020)

- The Kathmandu Post. 2020. [1]. Nepal goes under lockdown for a week starting 6am Tuesday. https://tkpo.st/2WCfoHW (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Kathmandu Post. 2020 [2]. Nepal and India agree to take care of and feed each other’s citizens stranded on the border. Crossings to remain closed. https://tkpo.st/2UNryeA (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Kathmandu post. 2020. [3]. Local units reimpose lockdown measures following rise in Covid-19 cases. https://tkpo.st/3a0K3U3. (Assessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Kathmandu Post. 2020 [4]. Nepali workers forced to work even under lockdown in Malaysia. https://tkpo.st/3bg7UhN. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Kathmandu Post. 2020. [5]. Covid-19: Impact and response. https://tkpo.st/2Spfmjt. (Accessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Rising Nepal. 2020 [1]. Locals Concerned Lest Quarantines Turn Out To Be Hotspots Of Coronavirus Transmission. https://risingnepaldaily.com/main-news/locals-concerned-lest-quarantines-turn-out-to-be-hotspots-of-coronavirus-transmission (Assessed 28 August, 2020)

- The Rising Nepal. 2020. [2]. Nepali Migrant Workers Start Returning To India Amid COVID-19 Threat In Lack Of Job At Home. https://risingnepaldaily.com/featured/nepali-migrant-workers-start-returning-to-india-amid-covid-19-threat-in-lack-of-job-at-home. (Assessed on 28 August 2020)

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship. 31, July 1995. Retrieved from Ministry of External Affaris, Government of India: https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/6295/Treaty+of+Peace+and+Friendship (Accessed 1 Oct, 2020)

- World Health Organization. 2020. Situation Update No.9- Coronavirus Disease 2019. WHO Country Office for Nepal.

Dr. Radheshyam Krishna KC has been working in the field of public health for the past 10 years. For the last 5 years working in the field of migration health. Dr. KC joined IOM during the 2015 Nepal earthquake and supported the implementation of public health related projects related to emergency and humanitarian settings. After completion of post-disaster projects, he worked as a migration health consultant to support IOM to draft the National Migration Health Policy and other key documents for the government of Nepal. Dr. KC has also worked as a migration health physician with hands on experience with immigrant health assessment. He is currently working as a Migration Health Officer and managing migration health projects to support the government of Nepal in various migration health related areas including COVID-19 response in the country. He is currently pursuing an M.Sc in Epidemiology from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He also has co-authored a number of publications in peer-reviewed journals such as Nature Science, BMC Public Health, Globalization and Health and so on.

Dr. Suraksha Chandrasekhar serves as the Emergency Health Support Consultant for the International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. She is currently providing technical support for IOM’s COVID-19 coordination and response efforts in the Asia-Pacific region. Upon graduating from Medical School, Dr. Chandrasekhar completed her Master’s in Disaster Medicine and Humanitarian Assistance from Thomas Jefferson University (USA) and had gone to work for the United Nations Secretariat in New York, where she provided technical and logistics assistance for the 2018 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak to the Department of Peace-Keeping Operations. She has previously worked for the American Red Cross (Philadelphia) and Life Again Foundation, a local NGO in India, in the field of disaster management, gender-based violence and reproductive healthcare, and advocacy for health rights and coverage, during humanitarian emergencies.

Dr. Montira Inkochasan, a Ph.D. in Applied Behavioural Science Research, is the Regional Migration Health Programme Support Officer for the International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. She has been working for IOM for 14 years supporting migration health projects and activities in Asia and the Pacific. Dr. Inkochasan has been providing technical supports to IOM’s migration health programme on HIV, TB, Malaria, pandemic, and emerging infectious diseases projects through supporting the development of concept papers, presentations, and reports through quality operational research, impact evaluations and reporting on key migration health themes and topics. She leads and/or provides oversight in qualitative, quantitative and applied research studies, mapping of mobility and health services, and development of behaviour change communication at the country and regional level. She has been involving in research work intensively for more than 10 years in wide range of issues and areas, namely in the fields of social, health, education and marketing. She managed IOM office and migration-related projects in Lao PDR for four years before joining the Migration Health Unit at the IOM Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

Dr. Patrick Duigan has been working in the field of migration health for the past 12 years in a range of humanitarian and development settings. He is currently serving as the Regional Migration Health Advisor with the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, based in Bangkok. In this capacity, he provides support and advice to IOM Country Missions, governments and local, regional and global partners to promote the migration health agenda across the Asia Pacific. Dr. Duigan completed medical school in Australia and has undertaken graduate study in Public Health, Tropical Medicine, Humanitarian Assistance and Child Health with Adelaide University, James Cook University, LSHTM, Liverpool School of Topical Medicine. Dr. Duigan has worked in numerous countries including Australia, PNG, Cambodia, Myanmar, Haiti, Philippines, Nepal and Thailand on a range of migrant health related programs including TB, HIV and Malaria Programming, Health System Strengthening approaches, emergency response and recovery and analysis and development of migration health policies. He has co-authored several publications on migrant health including those appearing in the BMJ, SEARO journal of Public Health and the Health and Human Rights Journal.

Citation

Radheshyam Krishna KC, Suraksha Chandrasekhar, Montira Inkochasan and Patrick Duigan. 2020. “Migration and COVID-19: Challenges for Nepal in Managing the Mass Exodus of Labor Migrants Returning from India” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.