Worldwide, over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, food production and distribution has been severely disrupted in a myriad of ways. This included panic-buying, delivery bottlenecks, export or import bans, sick factory and market workers which will have long-term economic repercussions. Around 20-25 million people are expected to experience poverty and malnutrition (Cook, 2020; Japan Times, 2020; Ruben, McDermott, and Brouwer, 2020). This has happened to such a degree that I am inspired to shed light on the attitudes and treatment of food, real and imagined, in my birthplace, Malaysia, before and during the enforced physical distancing by a partial lockdown, originally termed the “Movement Control Order” (MCO) and this was enforced by the Malaysian authorities (PMO, 2020; MOH, 2020).

The Catalan Chef Ferran Adria recently stated that “one thing that is going to come out of the lockdown is that some of the population are learning about cooking” (Hurriyet Daily News, 22 May, 2020). Chef Adria probably might not be referring to his rich clientele. After all his restaurant, El Bulli, is not your typical high-end restaurant as its specialty is high-tech molecular cuisine. Yet it is heart-warming nonetheless to know that top chefs have been taking note of what is happening in home kitchens. I do have a kitchen in my small condominium in Petaling Jaya, which is located in the Klang Valley conurbation that engulfs most of the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur the financial capital of Malaysia1.

Solace in the Age of Social Media

During the partial lockdown in Malaysia, the evidence showing numerous work-from home Malaysians regardless of gender, class, or spirituality, cooking up a storm in their kitchens was ample on social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and even Tik Tok). However, there was also something else at work here: Malaysians found light entertainment in food. Facebook pages such as “What Spoilt Cooking Have You Made Today” (Masak Apa Tak Jadi Hari Ni (MATJHN)) sprung up to give us an idea of some of the changes that have been initiated. The above Facebook group, which was launched on 14 April 2020 (MATJHN, 2020) and whose members are mostly Malaysians residing in the country, discusses how the lack of culinary skills can be celebrated and seen as a normal part of the process of self-improvement. Granted, many Malaysians were already on social media pre-lockdown (Kantar, 2014), but the lockdown itself saw a significant increase in internet traffic (Nambiar, 2020). As such, food-related voyeurism also led to a surge in screen time. Many though have been using the internet to push food sales. Better still, some are getting paid for sharing their skills in the kitchen on YouTube (Ng, 2020). A good example of this MCO-social media interaction is the story of Pavithra and her husband, Sugu, (Sugu Pavithra YouTube Channel, 2020). Their channel was created on 28 January 2020, but after receiving publicity from the National News agency, Bernama, on 8 May 2020, the number of subscribers shot from 160,000 to more than 640,000 within a month (The Star, 2020a). Besides their seemingly tasty meals, their “B40” background is somehow irresistible to many people. “B40” in Malaysia refers to the economically underprivileged who make up the bottom 40% of the citizenry, with household incomes of less than RM4000 (US$ 937) per month (PMO, 2020). The couple’s success caught the attention of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin, who recently gifted Pavithra and her family with kitchen utensils, groceries and a certificate of appreciation for their services to the country (Yoy Network, 2020). I do not want to question the PM’s motives, but I am in awe of this young couple’s confidence to turn their family recipes into an open business.

We should remind ourselves that learning to cook for the first time or cooking three meals daily for a family during the lockdown is a process of survival. Hopefully, skills, knowledge and enthusiasm will remain after the lockdown finishes. This may even help us to revive forgotten cuisines. That will be one clear upside to the lockdown because modern life has changed what we eat as well as our eating habits to such a degree that our centuries’ old food knowledge is lost. Information about what and how some villagers cooked and ate in the past was related to me in the early 2000s (2002-3), when I was conducting fieldwork in Negeri Sembilan (Hashim, 2006). In the past most villagers foraged for ferns, mushrooms and cinnamon bark in secondary forests scattered around their villages, whilst a few collected wild honey and trapped mouse deer or porcupines in the primary forests located farther away. However, this practice is now largely abandoned in preference for supermarket alternatives, bought using office salaries and labor wages. Of course, this intergenerational loss has occurred in my family as well; my mother is a last generation rice farmer, but her city-dwelling non-farming great-grandchildren do not even know the proper name of rice plants in Malay (their supposed mother tongue) because they do not need to know it.

The threat of being locked in at home for an extended period include abuse, harassment, dementia or even death, but for the lucky ones it may mean more time to finish house renovations (which I had started three years ago), more time for reading, writing or editing, and of course, more solace in the kitchen. This time available became apparent in another new Facebook group called “What Are The Husbands Cooking Today” (Suami Masak Apa Hari Ini?, (SMAHI?)) that is open to men. Because of my gender and vocation, I can only imagine what they mean by “This group is only for husbands and soon-to-be husbands. Wives are barred from joining” (Group ini hanya untuk geng suami dan bakal suami sahaja. Isteri2 takleh sama sekali join group ni: SMAHI?, 2020). Promptly I am wondering if these husbands are finding easy camaraderie online and much-needed breathing space from their children and wives at home.

Economies of Scale or Community Sufficiency?

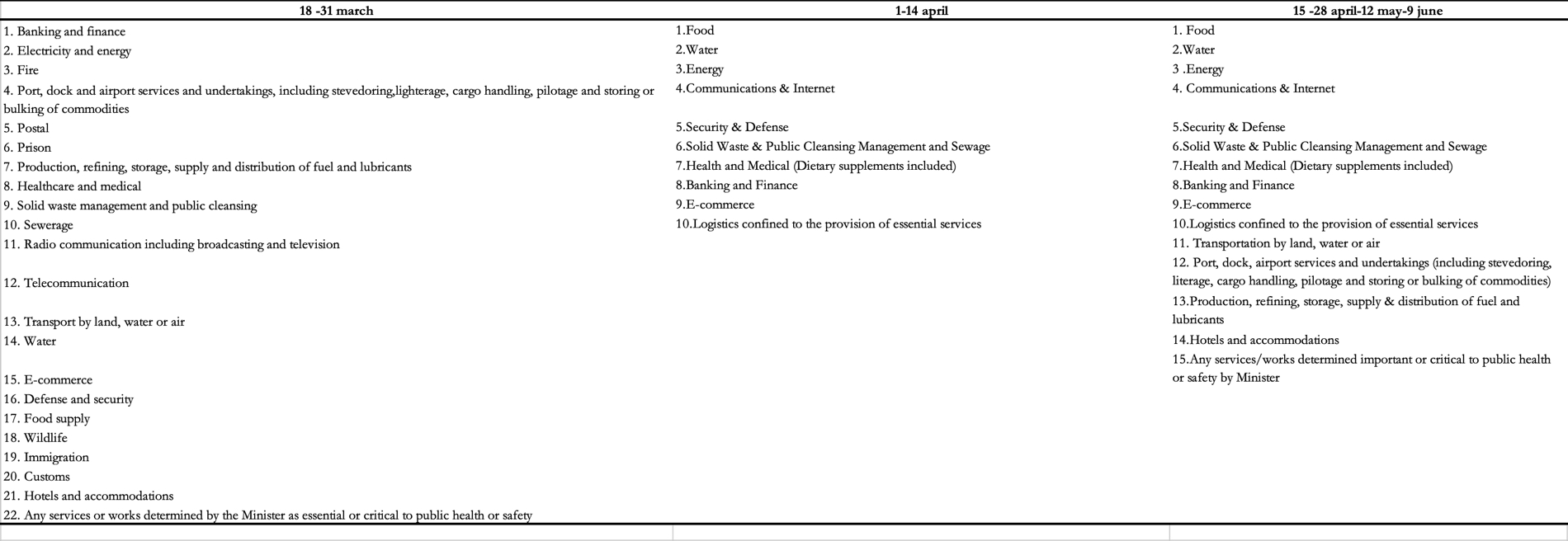

The impacts of COVID-19 on Malaysia’s food landscape and economy have had far reaching implications. Malaysia’s agricultural imports come from many countries, notably, China, India, Thailand, Indonesia and New Zealand (The Malaysian Reserve, 2019), which means that the COVID-19 travel restrictions out of these countries had massively affected Malaysia’s food supplies as well. Worse, Malaysia is a country with highly fertile lands, but it is growing mostly oil palms, from which fruit oil is extracted and converted into numerous products including soap and biodiesel that are then exported to Europe and China (Coca, 2020). Only a small fraction of that land is used for growing vegetables and fruits of which the Cameron Highlands is famous for. Fresh farm produce is ordinarily trucked via the North-South Expressway for convenient and fast delivery to the main wholesalers’ markets in Kuala Lumpur, from which produce then travels further down the supply chain to smaller retailers servicing consumers. Any event that blocks this expressway as well as the longer, meandering trunk roads, affects the food distribution and prices. This happened during the initial stages of the MCO, thus effectively disrupting businesses and causing millions of city dwellers to pay more for their fresh produce. The blame fell not on the MCO essential business listing (See table 1: Federal Gazette, 2020), rather it was due to national-scale confusion and miscommunication, which was quickly and concertedly rectified by businesses, civil society groups, and the authorities.

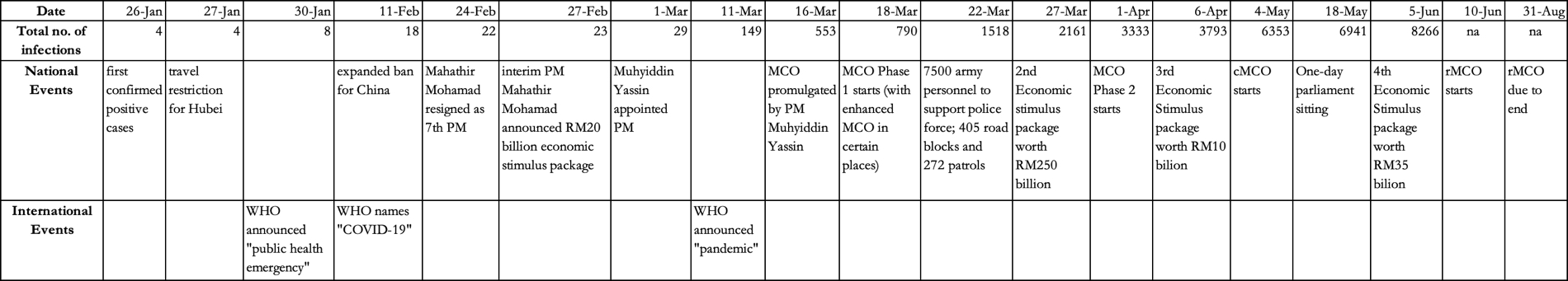

In the meantime, the MCO has been extended a total of five times, and under the latest phase, the MCO is expected to end on 31 August (See table 2: MOH, 2020; PMO, 2020; DSM, 2020; WHO, 2020; Khairulrijal, 2020). However, the economic impacts of the pandemic and the resultant lockdowns have been well-anticipated by those in power. Before stepping down Mahathir Mohamad announced a stimulus package specifically to assist the ailing tourism industry. Afterwards, Muhyiddin Yassin had announced three additional stimulus packages to cushion the economic blow on Malaysia (see table 2).

Table 2. Milestones of COVID-19 pandemic and Malaysia’s responses. Sources:1. Ministry of Health Malaysia. 2. Prime Minister’s Office Malaysia. 3. Department of Statistics Malaysia. 4. WHO. 5. Khairulrijal, 2020.

In the early days of the COVID-19 emergency, I witnessed panic buying in the city as I was shopping at various supermarkets, but somehow it did not feel overly frantic, e.g. Malaysians did not panic buy toilet rolls (this author did not buy any because she had done that during last December year-end sales, and she did not stock up on fresh produce because her fridge is small). Moreover, many people’s concerns and fears were allayed as the MCO was announced to be for a fortnight and that the markets would be still remain open. However, many Malaysians habitually buy fresh produce daily, especially in the morning at wet markets. In this case, it was convenient for the authorities to regulate physical distancing at such markets and order a complete shutdown (The Star, 2020b). Sellers and customers initially objected but swiftly relented, especially under the threat of a stiff penalty including gaol and a RM1,000 (US$ 234) fine (MOHA, 2020). Also, procuring food outside the homes whilst practicing physical distancing has been an inconvenience, if not a struggle, so many customers including myself, have opted to order fresh and cooked food online or on the telephone to be home-delivered (Hashim, 2020). When the annual open-air street bazaars (Bazar Ramadan) selling all manner of halal food were not permitted during the Muslim fasting month, which sadly this year coincided with the MCO, home deliveries became ever more fashionable. Further, eating out has been limited to a few restaurants that comply with temperature scanning, telephone number reporting, and spacing, which has greatly diminished the social ambience.

Eating out during the later phase of the MCO. The author waiting for her roti canai and frothy milk tea (being fetched by a waiter behind her) at one of the numerous Mamak restaurants, which are highly popular eateries in most Malaysian cities. Note the empty seats around, as well as the face masks on the waiters, who are mostly adult able-bodied male migrant workers from South India, and speaking passable Malaysian.

Indeed, the MCO situation is in stark contrast to pre-lockdown Malaysia when many were spoilt for choice, especially if they did not have any dietary requirements (religious and/or for health). For some time already, Malaysians have had access to a vast array of meals and fresh produce sold at a variety of premises (e.g. street kiosks, markets, stalls, cafes, restaurants, and food trucks), both legal and illegal. This urban diversity was several decades in the making. Growing up in 1970s through to the early 1990s in a village located about 120km by road from Kuala Lumpur I observed first-hand how Malaysia – at least my side of it – drastically changed in the second part of the 20th century (but for scholarly analysis I urge my readers to refer to e.g. Jomo (1993)). Earnest rural-to-urban migrations by primary-school and high-school leavers started in the 1980s when transnational electronics and electrical parts and assembly companies profiting from this supply of low-wage labor, started to set up their factories around Kuala Lumpur, Petaling Jaya, Seremban, Penang, Johor Baru (these town centers had reliable transportation networks, water and electricity supplies). These factories employed mostly young women (minah karan) including four of my elder sisters to manufacture integrated circuits and so on and this often required a high level of concentration, long hours, and deft hands to make. Otherwise, in the construction sector, where brute strength, long hours and little conversation was required, young men labored to build the soon-to-be skyscraping cities. These factory and construction workers needed to buy ready meals as they did not have much time to cook, albeit possessing fair cooking skills, in their hostels or on site, and although transboundary fast-food restaurants were starting to become aplenty, e.g. McDonald’s has had outlets operating since 1982 in West Malaysia (McDonald’s Malaysia, 2020), their hamburgers, hotdogs, soda and fries were still expensive. In contrast, the homegrown Ramly burgers street kiosks, which started business in 1984 (Ramly, 2020), sold their burgers and egg-banjos sans drinks for much cheaper, thus affordable to low-income workers, who also had to send remittances to their families in villages. However, their mainstay meals were actually white rice and the assortment of accompanying curries and vegetables dishes that were sold by roadside stalls (warung). Over time more food restaurants serving these simple meals sprang up so as to feed more hungry mouths. We can therefore visualize how these individuals, recently uprooted from their birthplaces into a weird city, already brimming with strange folk, were suffering from homesickness and finding shared association and comfort and this led to the rapid formation of disparate socio-economic cultural groups that cooked their familiar foods only for themselves. They hardly noticed that despite each group’s peculiarity in food preparation, the ingredients they all used originated from the same places. In those days it was easy to categorize by class, ethnicity or region familiar foods, but this was quickly attenuated when increasingly more sophisticated palates and bigger wallets started craving for more heterogeneity.

A group of friends waiting to enjoy their food and drinks at a restaurant serving ‘Chinese food’ pre-MCO. White rice with an assortment of ‘accompanying’ dishes. The white on black signage at the back says “Muslims are not permitted to buy or drink alcoholic drinks” (Orang Islam Dilarang Membeli atau Meminum Minuman Keras).

By the early 21st century the emerging Malaysian economy has shifted nearly half the population, not necessarily into the burgeoning middle class, but always away from rural agriculture or fishing families into growing cities. Most have high hopes for employment, food, cleanliness, entertainment, education and to keep cities secure and healthy. Their work is either general or specialized, formal or informal, with various differences in salary, but cities are still seen by many as spaces that provide real opportunities for upward social mobility (Faizah, 2008). Therefore, it is easy to understand how so many different foods have been easily sold on the same streets or in the same restaurants pre-lockdown. Irrespective of multi-traditions and different groups, the old and new have been, over the years, assimilated, integrated and co-opted. It rightly feels pointless to talk about body politics via food categorizations, unless perpetuated by those with much to gain, either in politics, business and even academia. Moreover, the culinary industry’s openness and inclusivity is evidenced by its innovations in fusion food and molecular cuisine, as well as its willingness to use sustainably produced ingredients. This latter categorization is arguably still reductionist, but the practice of food-making and eating has become less about questionable ethnic demarcations or false national identity, and more about raising an industry’s gold standards.

Our collective global response to the pandemic has been to socially shut down, which has truly tested our disaster preparedness. On an individual level, being lucky means possessing the knowledge, support and wherewithal to live comfortably through the numerous features of lockdowns (self-isolation, physical distancing, travel restrictions, closed businesses etc.) for several months. These personal capacities and capabilities vary amongst us, but in the context of food (including nutrition) security, those who are able to feed themselves and their communities seem to have shown resilience during these uncertain times. For example, my architecturally-trained youngest sister, who for a decade has been growing fruits and vegetables, raising chickens, rabbits (along with her pet cats and a dog) on an 1-acre home garden, has told me that she and her like-minded, permaculture neighbors were quite self-sufficient, therefore they did not ask for food aid packages.

Clearly, this food story is still unraveling as we are continuously shattered by the mainshock of COVID-19, which in an unprecedently short time, has changed the ways we deal with food. Coming out of the lockdown we will experience a Malaysia – and one may say our entire planet – of deeper and wider social and economic inequalities, wherein the foods that many, if not most, find, grow, make, cook and consume, will vary not only in quality but also in quantity. Just remember that it was human food that served as a likely vessel from which the COVID-19 virus jumped from host to host (Maron, 2020). How remarkably humbling.

10 June, 2020

References

- Coca, Nithin.2020. As palm oil for biofuel rises in Southeast Asia, tropical ecosystems shrink. chinadialogue. 15 April. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/11957-As-palm-oil-for-biofuel-rises-in-Southeast-Asia-tropical-ecosystems-shrink. (Accessed 7 June, 2020).

- Cook, Christopher D. 2020. Farmers are destroying mountains of food. here’s what to do about it. The Guardian. 7 May. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/may/07/farmers-food-covid-19. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia (DSM). 2020. https://ukkdosm.github.io/covid-19. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- Faizah, Mohd Tahir. 2008. Population Distribution, Urbanization, Internal Migration and Development. New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/pdf/commission/2008/country/malaysia.pdf. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Federal Gazette. 2020. Attorney-General’s Chambers Malaysia. http://www.federalgazette.agc.gov.my/. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- Hashim, Nor Rasidah. 2006. Anthropogenic Tropical Forests In The 21st Century: The Creation, Characteristics And Uses Of Secondary Forests In Negeri Sembilan, Peninsular Malaysia. PhD Thesis. Department of Geography, University of Cambridge.

- Hashim, Nor Rasidah. 2020. Food delivery in the city: A boon or bane? Bernama. 22 May. https://www.bernama.com/en/thoughts/news.php?id=1844109. (Accessed 5 June, 2020).

- Hurriyet Daily News. 2020. A world redrawn: top spain chef sees fewer restaurants, more home cooking. 22 May. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/a-world-redrawn-top-spain-chef-sees-fewer-restaurants-more-home-cooking-154983. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Japan Times. 2020. Amid pandemic, it’s getting a lot harder to ship food around the world. 10 April. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/04/10/world/shipping-food-pandemic/#.Xsujl0QzbIU. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Jomo, Kwame Sundaram, ed. 1993. Industrializing Malaysia: Policy, Performance, Prospects. New York: Routledge.

- Kantar. 2014. Malaysian internet users amongst the most socially engaged in the world. 23 September. https://www.tnsglobal.com/press-release/malaysian-internet-users-amongst-most-socially-engaged-world. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Khairulrijal, Rahmat. 7,500 military personnel enforcing MCO nationwide. New Straits Times. March 23, 2020. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/577213/7500-military-personnel-enforcing-mco-nationwide. (Accessed 6 Jun,e 2020).

- Maron, Dina Fine. 2020. ‘Wet markets’ likely launched the coronavirus. here’s what you need to know. National Geographic. 15 April. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2020/04/coronavirus-linked-to-chinese-wet-markets/ . (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Masak Apa Tak Jadi Hari Ni (MATJHN). 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/matjhn.official/. (Accessed 22 May 2020).

- McDonald’s Malaysia. 2020. https://www.mcdonalds.com.my/company. (Accessed 6 June, 2020).

- Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH). 2020. http://COVID-19.moh.gov.my/. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- Ministry of Home Affairs Malaysia (MOHA). 2020. http://www.moha.gov.my/images/terkini/FAQ_KDN_21_MAC_2020_update_21_Mac_20204pm.pdf. (Accessed 10 June 2020).

- Nambiar, Predeep. 2020. 30% spike in internet usage during MCO but TM says it can handle more. Free Malaysia Today. 1 April. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2020/04/01/30-spike-in-internet-usage-during-mco-but-tm-says-it-can-handle-more/. (Accessed 25 May, 2020).

- Ng, You Jing. The 10 best Malaysian Youtube Channels for learning how to cook. Jobstore. April 24. https://www.jobstore.com/careers-blog/2020/04/24/the-10-best-malaysian-youtube-channels-for-learning-how-to-cook/. (Accessed 6 June, 2020).

- Ruben, Ruerd; McDermott, John; and Brouwer, Inge. 2020. Reshaping Food Systems After COVID-19. 20 April. Washington DC: CGIAR. https://a4nh.cgiar.org/2020/04/20/reshaping-food-systems-after-COVID-19/. (Accessed 26 May, 2020).

- Prime Minister Office of Malaysia (PMO). 2020. https://www.pmo.gov.my/. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- Ramly. 2020. https://www.ramly.com.my/. (Accessed 6 June 2020).

- Suami Masak Apa Hari? (SMAHI). 2020. https://www.facebook.com/groups/matjhn.official/. (Accessed 5 June, 2020).

- Sugu Pavithra YouTube Channel. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC7mNwREuYU-Bc8glCdFwQ_A/about. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- The Malaysian Reserve. 2019. Food import bill hits RM34.2b as of August. 19 November. https://themalaysianreserve.com/2019/11/19/food-import-bill-hits-rm34-2b-as-of-august/. (Accessed 6 June, 2020).

- The Star. 2020a. Penang to close public markets not complying with MCO. 23 Mar. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/23/penang-to-close-public-markets-not-complying-with-mco. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- The Star. 2020b. Malaysian couple behind YouTube sensation ‘Sugu Pavithra’ says they don’t deserve titles of ‘unity ambassador’ or ‘cooking icon’ yet. 9 June. https://www.thestar.com.my/tech/tech-news/2020/06/09/malaysian-couple-behind-youtube-sensation-sugu-pavithra-says-they-dont-deserve-titles-of-unity-ambassador-or-cooking-icon-yet. (Accessed 10 June, 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. https://www.who.int/. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

- Yoy Network. 2020. 16 May. https://www.yoy.my/video-plan-nak-masak-untuk-jiran2-kami-sugu-pavithra-kongsi-hadiah-dari-pm/. (Accessed 22 May, 2020).

Nor Rasidah Hashim is an independent researcher based in Peninsular Malaysia. Trained for many years in the natural sciences on the big islands of Britain, Borneo and North America. Nor is now interrogating her knowledge and lived experience through the intersectional and transdisciplinary projects of landscape planning and biogeography, and an affiliate at the Institute of Landscape Planning, Universität für Bodenkultur Wien, Austria.

- 1 A small note: every time I write “Malaysians” in this article, I am, more likely than not, referring to those from the city like myself.

Header IMG: Street view of a weekly night street market in Petaling Jaya, in the second week after re-opening. Physical distancing is in place with clearly reduced customer and seller numbers, as well as the lack of heterogeneity of sold items. (Source: Author)

Citation

Nor Rasidah Hashim. 2020. “A Truly COVID-19 Malaysian Food Story” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.