The implementation of large-scale social restriction (Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar, PSBB) in Indonesia has put the working class in a more precarious condition. Moreover, while public mobility and activities are put on hold, the Indonesian Parliament insisted to hold a session for the controversial draft of Omnibus Law. This law has been the subject of criticism from labour unions and other social movements because it undermines workers’ rights, even after a series of strong protests against it prior to the formal announcement of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.

The Indonesian Parliament’s continuing insistence to pass the pro-investment law shows the government’s priority in getting the economy ‘back on track’ as a ‘business as usual’ approach. Equally important however, one should also ask about what constitutes the real backbone of the economy – the millions of vulnerable workers at risk from the effect of crisis. Amid strained circumstances, activists, trade unionists, and people from different organisations are building collective solidarity and designing community resilience. This crisis has created a gendered experience of the working class. Nevertheless, various strategies of people’s alliance in initiating people to people solidarity are also emerging. The challenge now is to reimagining solidarity beyond a conventional first-aid response to a disaster.

COVID-19, Class and the Gender Dimension

The lockdown decision or mass quarantine complies with the Law No.6/2018 on Health Quarantine. Although the severity of the pandemic has necessitated the implementation of quarantine measurements, President Joko Widodo instead opted for the issuance of PSBB instead of a comprehensive lockdown or regional quarantine. According to the law, quarantine would imply the provision of people’s basic needs and foods by the central government. This would allow people to have guaranteed rights and equal access to basic health services, food, and daily needs such as clothes and hygiene during the quarantine. This is different from PSBB also known as partial lockdown, since it focuses on the closure of schools and offices and the limitation of religious activities and public gathering without any guaranteed provision of services from the central government. Thus, as people are forced to stay at home, class and gendered dimensions of this pandemic have became prevalent. We can see this in the experience of working class mothers.

As of now over 1.2 million workers, both formal and informal sectors nationwide, have been furloughed or laid off due to the pandemic. When added with the numbers of workers who are in the verification and validation process, the total amount of workers affected now reaches up to 3 million. Among these are 800 factory workers at the Kawasan Berikat Nusantara (KBN) industrial complex in Cakung, East Jakarta. According to the Inter-Factory Workers Federation (FBLP), half of these workers are women. They all are the breadwinners for their families, with up to five children per household. The 400 women factory workers who have been in unpaid leave are struggling to provide foods and pay house rent. Another problem is their residential status. Although they live in Bekasi and North Jakarta, most of them are listed as residents in their places of origin, instead of in Jakarta. Thus, they cannot receive the government assistance package since beneficiaries must be registered as Jakarta’s local residents. This worsens the condition of women workers, who have been subjected to various poor working conditions such as sexual abuse, outsourcing, and companies’ constraints on maternity leave.

Their constant renewable outsourcing status exposes the vulnerable definition of formal and informal workers. The status of formal workers within this system is proven to be as precarious as with informal workers. Companies tend to hire women workers on short term contracts to avoid possible obligations such as paid maternity leave, and when the workers are pregnant, their contract are not renewed. Not only do they become disposable, but they are put in limbo between the multiple burden in the sphere of social reproduction as mothers and breadwinners, and the sphere production as labourers under uncertainty of their job status.

This example shows that we are in the crisis of social reproduction. Social reproduction can be understood as the reproduction of life itself, including reproduction and caring for others, production activities in households, and informal work that sometimes challenges the cultural infrastructure of social relations (Rai et al, 2019). However, this social reproduction sphere is considered a given sphere for women and henceforth the discrimination and injustice that derives from it are deemed as socially acceptable, thus justifying the current structure of gender inequalities (Bhattacharya, 2015). Women workers in various workplaces – from factories, health services, care work, to essential job sectors that sustain the economy during pandemic – are central to the national economy and global production. These frontline workers receive less wages and have little access to proper health and social protection. Many of them are also working class mothers, who disproportionately bear the burden of social reproduction during the crisis.

A closer look at the gendered dimension of informal work reveals the problem of hidden poverty. The 2018 ILO Report found that the poverty rate between men and women in informal work in general and in particular among countries with high poverty rate shows that there are more women living in households below the poverty line than men. In Indonesia, 74.08 million informal workers made up 57 percent of all workers in 2019, including a significant gender pay gap where men are paid higher than the women in average (IDR 3.05 million (US$ 204) for men compare to IDR 2.79 million (US$ 187) for women). The pandemic has caused the decline in the production of manufacture industry in Indonesia and globally, making the lives of the 16.3 million of the majority women workers in the industry even more precarious.

It is crucial to step back and acknowledge that the crisis of social reproduction brought along within this pandemic is part of the broader trend of crisis. The 2008 global economic crisis destroyed both financial and real sector in Indonesia, causing the mass layoffs of approximately 79.026 workers. It was found that the impact was relatively stronger within rural households than in urban households, but since the job market is deemed more flexible, the unemployment rate in rural areas is less than those in the cities. This flexibility affects the circular rural-urban migration and contributed to the high rate of informal workers.

The current situation also shows the disposability of the workers apropos to their relations with capital. The root cause of this is the three decades of neoliberal policy in Indonesia based on land dispossession, labour-intensive industries and cheap labour for capital accumulation while undermining employment creation and decent work (Habibi and Juliawan, 2018). The rising unemployed and informal working class in Indonesia has created a surplus population relative to the availability of industries as the source of their employment.

The government is planning to evaluate reopening the economy in June-July through five phases with the expectation that all normal economic activities will resume by August this year. For women, care work has its gendered meanings and practices that are barely acknowledged by the decision makers and this pandemic adds up to their burden. A push to reopen the economy without a significant government investment in public health, environmental protection, and workers’ rights would only drag more people to be exposed to the virus and the continuation of the current form of labour exploitation.

People to people

Currently there are more than 32.000 COVID-19 cases in Indonesia. Jakarta is the epicentre of the pandemic with 8000 confirmed cases, far above other provinces (as of time of writing). In the shadow of the spread of the pandemic, the poor have limited access to facilities and qualified health services and are find themselves under increasing precarious employment conditions. Meanwhile, the state, business sectors and yellow trade unions prefer to put profit before the workers’ life, either by keeping up the workers’ normal pace, furloughing or adjusting the pace of production. In the pursuit of maintaining and accumulating capital, the minimum requirements needed to keep workers’ production and social reproduction capacity barely provides them with a survival thread.

This situation seems to undermine the fact that factory workers are likely to be infected with COVID-19, particularly in factories where workers are put under the same working condition as in normal days. At least until the end of March, most of the workers in KBN Cakung still carry out production activity eight hours work per day from Monday to Friday. Physical distancing is also difficult in practice within the factory and workers have complained about inadequate facemask and hand sanitizer. In early May, two workers at a Phillip Morris tobacco factory in Surabaya, East Java, died from COVID-19, while 123 of them were diagnosed to have the symptoms and this forced 500 workers to undergo quarantine. Another case occurred at the Freeport Mining Company in Mimika, Papua, where 52 cases were found among its workers, and one of them, subsequently, died. Despite the already prolonged destitution suffered by Papuans due to the exploitation and environmental damage caused by Freeport, there is no instruction to halt the company’s operation.

In general, people have initiated various ways to respond the pandemic through philanthropy, charities, social assistance, to online public discussions and seminars. Political parties and mass organisations distributed donations to communities. Two most established and well-funded Islamic organisations in Indonesia, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, are quickly distributing their donations amounted to billions of rupiah to communities in Jakarta and across the nation. However, several organisations have also initiated ‘people to people solidarity’ or rakyat bantu rakyat platforms, a series of spontaneous social movement initiatives to provide urgent assistance for those who are most affected by the pandemic. Different from the top-down charities of political parties and big mass organisations, these are built by activists and communities of the working class as a political act of resistance.

In Jakarta, some organisations are initiating people to people solidarity for the specific communities to respond to this situation. One example is a collaboration between the Progressive Islamic Forum (FIP), the Jakarta Urban Poor Network (JRMK), the Indonesian Peoples’ Union of Struggle (SPRI), the Transgender Community of Kampung Duri, the Indonesian Women Coalition (KPI) and the victims of Tamansari forced eviction in Bandung, West Java. They have campaigned and collected donations for the urban poor and marginalised communities in the targeted area.

During the holy month of Ramadhan, FIP and FBLP worked together with Nahdliyin Front for the Sovereignty of Natural Resources (FNKSDA) to collect funds for the 400 women factory workers affected by COVID-19. They brought independent folk musicians to launch a series of online concerts via YouTube and invited people to watch while donating through various payment platforms. Each online concert is accompanied with a discussion on a specific theme about building an alternative solution. They do this on the basis of zakat (an obligatory charity under Islamic law during the holy month) to use the momentum and start a discussion on longer term plans in consolidating a progressive social movement. With their affiliate media partner, Islambergerak.com, they are offering an alternative perspective by consistently focussing discussions and debates on contemporary cases of forced eviction, agrarian reform, poverty, environmental degradation and workers’ rights embedded within the interpretation and manifestation of Islamic teaching from a social justice aspect.

In Jogja (Yogyakarta), activists, students and homemakers initiated Jogja’s Food Solidarity (Solidaritas Pangan Jogja) by establishing public kitchens in several areas. They cooked meals to be distributed to mostly informal workers who are affected by the pandemic. By pursuing food solidarity as their core activity, they are also working towards ecological justice as an alternative to community’s resilience. In Bandung, a diverse alliance of actors established a public kitchen along with a discussion on building an alternative food system by partnering with local farmers. They are mostly informal workers consist of independent artists, anarcho-activists, market sellers, and other community organisations. Many of them have been actively engaged in defending workers’ rights, land rights, and victims of the Tamansari forced eviction1. This kind of solidarity helps connect people with various experiences of state’s repression and negligence by facing the pandemic together as one community and as the voice of the working class.

Reimagining solidarity

What might this people to people solidarity mean for the working class who are bearing the burden of the COVID-19 crisis? At the time of natural disaster, financial collapse, post-war recovery and pandemic, people rebuild lives and reconnect with each other in a way that is different from ‘normal’ time. Their resilience is crafted not only by values, belief, and culture, but also by their material conditions. For the working class in Jakarta, this means the capacity to face dense urban habitation, traffic congestion, overcrowded transportation for commuting, worsening seasonal floods, a lack of green public spaces, and the widening gap between the rich and the poor.

The large Islamic holiday of Eidul Fitr (the breaking of the fast) also poses another challenge. After fasting for a full month during Ramadhan, Indonesian Muslims in big cities, mainly Jakarta, will typically return to their respective home villages (mudik) to celebrate the festive season with their families. The government has issued a prohibition of mudik in order to prevent a mass spread of COVID-19 upon returning to their hometowns. While many violate this instruction, workers affected by the crisis are unable to mudik. Hence, there is apparently an increase in homelessness in Jakarta where they are stranded with no place to live because they are no longer able to pay a roof to rent.

With regulations to address COVID-19 such as PSBB, stay-at-home, and work-from-home, many Jakartans would find it hard to survive simply because they do not have the means and privilege to do it. This is no longer a question of rebuilding solidarity every time there is an outbreak, disaster or unanticipated calamity occurs as a ‘safety net’ for the country. But it is about building a solidarity that goes beyond a mere rescue valve.

When we try to reimagining solidarity, we need also reimagine nationalism and the economy. This requires a rethink about the politics of a cross-section of the working class that encompass the horizon put forward by women workers and the urban poor. Imagining solidarity for the working class in Jakarta is not about fixed locations and identity. Many of them are circular rural-urban migrants who do seasonal and informal work in Jakarta but are still attached to and reside in their hometowns outside of Jakarta. They came from neighbouring and distant provinces, struggling to find a living as their villages are enduring agrarian transformation, land dispossession, and a lack of unemployment opportunity in general. This dynamic interaction can be understood in the context of unequal power relations along with mobility, movement and spaces that maintain their livelihood. Thus, it is crucial to build a spatial-sectoral solidarity between rural and urban areas and between the industry and farming sectors. Such an ecosystem mutually reliant and has the strong potential of unifying the fragmented working classes from different labour regimes such as those who work in formal or informal settings those who work for individual entrepreneurs or companies and bring people to people solidarity forward.

The current pandemic crisis spiralled from the multiple crisis in our global system – economy, health policy, and ecology, to name a few. The ‘people to people’ initiative aims to consolidate efforts beyond the conventional paradigm of philanthropy. We need a long-term vision of equality and need to champion a collective struggle to anticipate future crises and ignite a transformative change. It is thus imperative to reclaim the space of philanthropic approaches and transform it into a movement of and for the poor, indigenous communities, and the working class in general. This can create a richer and more active political agency for a more sustainable and resilient future.

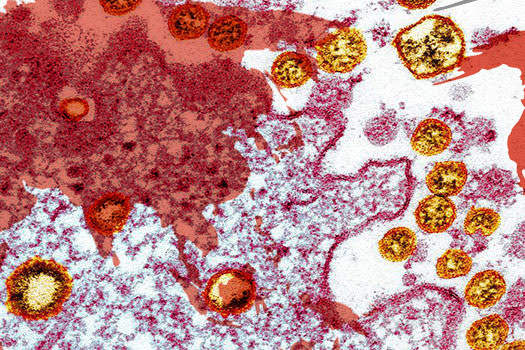

A representative from Inter-Factory Workers Federation (FBLP) received zakat (Islamic charity) from people to people solidarity initiatives for 400 women factory workers affected by the pandemic crisis. Photo by Ari Widastari.

25 May, 2020

[The author would like to thank Angga Yudhiyansyah, Muhammad Azka Fahriza, and Ahmad Thariq for their valuable inputs and discussion]

References

- Adam, Aulia. 2018. Tangan dan Kaki Terikat: Buruh Perempuan di Cakung Dilarang Hamil [Bounded Hands and Legs: Women Workers in Cakung Are Prohibited from Getting Pregnant]. Tirto.id. https://tirto.id/tangan-dan-kaki-terikat-buruh-perempuan-di-cakung-dilarang-hamil-daRr (Accessed 21 May, 2020).

- Badan Pusat Statistik. 2019. Februari 2019: Tingkat Pengangguran Terbuka (TPT) sebesar 5,01 persen [February 2019: Open Unemployment Rate is 5.01 percent]. 5 June. https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2019/05/06/1564/februari-2019–tingkat-pengangguran-terbuka–tpt–sebesar-5-01-persen.html (Accessed 20 May, 2020).

- Bappenas. 2009. Buku Pegangan 2009 Bab II: Penyebab dan Dampak Krisis Keuangan Global [Handbook 2009 Chapter II: The Causes and Impact of Global Financial Crisis]. https://www.bappenas.go.id/files/2413/5027/3724/bab-2handbook-2009050509__20090518110628__1.pdf (Accessed 16 May, 2020).

- Beritasatu. 2020. Indonesia Quarantines Over 500 Philip Morris Factory Workers. Jakarta Globe. 3 May. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/indonesia-quarantines-over-500-philip-morris-factory-workers (Accessed 30 May, 2020).

- Bhattacharya, Tithi. 2015. How Not To Skip Class: Social Reproduction of Labour and the Global Working Class. October 31. https://www.viewpointmag.com/2015/10/31/how-not-to-skip-class-social-reproduction-of-labor-and-the-global-working-class/ (Accessed 16 May, 2020).

- Chew, Amy. 2020. As homelessness rises, Indonesia debates how to ease coronavirus restrictions and restart economy. South China Morning Post. 14 May. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3084417/homelessness-rises-indonesia-debates-how-ease-coronavirus (Accessed 20 May, 2020).

- CNN Indonesia. 2020. Imbas Corona, Utilitas Manufaktur Anjlok Hampir Separuh [The Impact of Corona: Manufacture Utilities Slumped to Almost Half]. 2 April. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20200402183754-92-489761/imbas-corona-utilitas-manufaktur-anjlok-hampir-separuh (Accessed 18 May, 2020).

- David, Hans. 2017. The unheard voices of female workers at their workplaces. The Jakarta Post. 2 May. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/05/02/the-unheard-voices-female-workers-their-workplaces.html (Accessed 20 May, 2020).

- Firdaus, Febriana. 2020. Indonesians Fear Democracy Is the Next Pandemic Victim. Foreign Policy. 4 May. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/04/indonesia-coronavirus-pandemic-democracy-omnibus-law/ (Accessed 20 May, 2020).

- Gugus Tugas Percepatan Penanganan COVID-19. 2020. Peta Sebaran [Distribution Map]. https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran (Accessed 30 May, 2020).

- Habibi, Muhtar and Benny Hari Juliawan. 2018. “Creating Surplus Labour: Neo-Liberal Transformations and the Development of Relative Surplus Population in Indonesia.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48:4, 649-670.

- International Labour Organization Report. 2018. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. Third Edition. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_626831.pdf (Accessed 21 May, 2020).

- Iswara, Made A. 2020. 1.2 million Indonesian workers furloughed, laid off as COVID-19 crushes economy. The Jakarta Post. 11 April. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/04/09/worker-welfare-at-stake-as-covid-19-wipes-out-incomes.html (Accessed 18 May, 2020).

- Kompas.com. 2020. Menyoal Kasus Covid-19 di Freeport, 52 Pasien Positif Corona hingga Bupati Minta Operasional Ditutup Sementara [On Covid-19 Case in Freeport, 52 Patients Are Corona Positive, Regent Asks for Operational Temporary Closure]. 9 May. https://regional.kompas.com/read/2020/05/09/14150091/menyoal-kasus-covid-19-di-freeport-52-pasien-positif-corona-hingga-bupati?page=1 (Accessed 30 May, 2020).

- Kurniawan, Alhafiz. 2020. Satgas NU Peduli Covid-19 Jakarta Salurkan Bantuan 1,1 Miliar untuk Warga [NU Taskforce for COVID-19 in Jakarta Distributed Assistance 1.1 billion to Communities]. NU Online. 29 April. https://www.nu.or.id/post/read/119578/satgas-nu-peduli-covid-19-jakarta-salurkan-bantuan-1-1-miliar-untuk-warga (Accessed 30 May, 2020).

- Manurung, M. Yusuf. 2020. DIlema Buruh Pabrik di Tengah Pandemi Corona [Dilemma of Factory Workers in the Time of Corona Pandemic]. 26 March. https://metro.tempo.co/read/1324039/dilema-buruh-pabrik-di-tengah-pandemi-corona/full&view=ok (Accessed 29 May, 2020).

- Mezzadri, Alessandra. 2020. A crisis like no other: social reproduction and the regeneration of capitalist life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Developing Economics. 20 April. https://developingeconomics.org/2020/04/20/a-crisis-like-no-other-social-reproduction-and-the-regeneration-of-capitalist-life-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (Accessed 20 May, 2020).

- Nashrullah, Nashir. 2020. Total Penerima Manfaat Bantuan Covid-19 Capai Jutaan Jiwa [Total Beneficiaries of Covid-19 Assistance Reached Millions of Lives]. Republika Online. 14 May. https://republika.co.id/berita/qabeyl320/total-penerima-manfaat-bantuan-covid19-capai-jutaan-jiwa (Accessed 30 May, 2020).

- Poerana, Sigar A. 2020. Hak Rakyat Jika Terjadi Lockdown [The Rights of The People When Lockdown Occurs]. Hukumonline. 2 April. https://www.hukumonline.com/klinik/detail/ulasan/lt5e74a69e9bf8d/hak-rakyat-jika-terjadi-i-lockdown-i-/ (Accessed 19 May, 2020).

- Rai, Shirin M., Benjamin D. Brown, Kanchana N. Ruwanpura. 2019. “SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth – A gendered analysis.” World Development (113): 368-380.

- Sofuroh, Faidah U. 2020. Data Kemnaker: Pekerja Terdampak COVID-19 Capai Sekitar 3 Juta Orang [Data from Ministry of Manpower: Workers Affected by COVID-19 Reach Up to 3 Million]. Finance Detik. 10 May. https://finance.detik.com/berita-ekonomi-bisnis/d-5009421/data-kemnaker-pekerja-terdampak-covid-19-capai-sekitar-3-juta-orang (Accessed 19 May, 2020).

- Yasmin, Nur. 2020. Gov’t to Use Pandemic Reproduction Number to Evaluate Reopening of the Economy. Jakarta Globe. 19 May. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/govt-to-use-pandemic-reproduction-number-to-evaluate-reopening-of-the-economy (Accessed 21 May, 2020).

Rizki Amalia Affiat is an activist at Progressive Islamic Forum (FIP) based in Jakarta. She holds an MSc in Violence, Conflict and Development from School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

- 1 The Tamansari case was the forced eviction of local inhabitants in Tamansari, Bandung, carried out by the police and public order agency (Satpol PP) in December 2019. It was based on the mayor’s instruction for gentrification on the pretext that the land is government’s owned, although this claim was controversial and swiftly challenged by the inhabitants. The process was without community’s participation. The evacuation was executed when the community was still filing a lawsuit in the city administrative court. The security apparatus used tear gas and physically attacked inhabitants during the clash. Indonesia’s National Human Rights Commission has announced the case involved human rights violation.

Citation

Rizki Amalia Affiat. 2020. “People to people: Covid-19 and Reimagining Solidarity Among the Working Class in Jakarta” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.