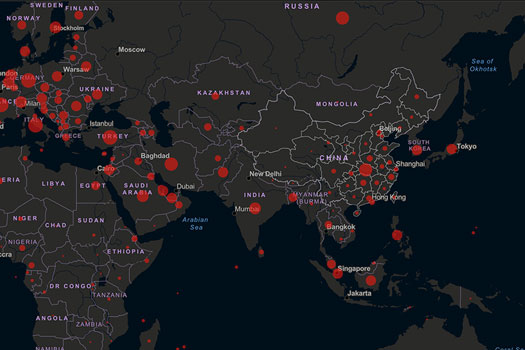

Nearly two months after the deadly COVID-19 virus arrived in Thailand, the Thai government’s initial laidback approach to dealing with the disease quickly changed when a large cluster of infections erupted early March at a scandal-ridden military-run boxing ring in Bangkok. At the time, growing frustrations over shortages of surgical masks and alcohol-based sanitizer were coupled with the controversial 21 February dissolution of the Future Forward Party, which had a cult following among the new generation. Political protests led by university students mushroomed in various parts of the country into the biggest campus protests in decades. It is not surprising, then, that towards the end of March 2020, the government invoked the draconian emergency decree, giving it vast powers to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, a measure more about controlling the population than the virus.

Of particular interest is how the Thai state has exploited the important Ministry of Interior to implement control measures aimed at suppressing the virus, in ways reminiscent of the repressive atmosphere under military rule between 2014 and early 2019.

The highly centralized Thai government made an unprecedented move by delegating powers to provincial governors— senior Ministry of Interior bureaucrats—to use their discretion to issue orders. The Ministry of Interior thus has taken center stage in the lead to “control” COVID-19 in Thailand’s provinces.

In Ubon Ratchathani where I am based, more than 10 provincial orders and announcements signed by the governor have been issued between March and May 2020. These orders strengthened the image of the Ministry of Interior as a ruling, not a governing body and thus maintained a vertical distance from the people over whom it “rules.”

A food cart abandoned near Ubon Ratchathani’s urban recreational park popular for its night dining, which has come to a halt due to the curfew.

First, the orders were not merely written texts full of statements describing states of affairs. They constituted what linguists call speech acts (act of doing something by saying it). They were speech acts of ordering. These speech acts reinforced the authority and power of the state (proxied by the province) to control the public’s behavior. Controlling people during these times is a common measure used around the world, but Thailand’s reliance on the Ministry of Interior to control the public during the virus period is done in the spirit of ruling at the expense of its other important duties—governing. These orders required certain businesses to temporarily close, village health volunteers and village heads to monitor village residents and visitors, individuals to observe “sanitary habits,” and ordered travelers from elsewhere to self-quarantine for 14 days. The orders barred groups of more than 50 individuals from gathering, barred individuals from travelling across provinces, barred academic institutions from holding physical class meetings, and barred individuals from being outside their homes between 10 pm and 4 am. Those most affected were those whose livelihoods were directly impacted such as night-market petty vendors, and the employees of businesses that were closed, mostly the urban poor or urbanized villagers. While members of the public have obeyed these orders, they have become increasingly frustrated by the lack of sufficient economic assistance from the government.

All of these gubernatorial orders cited the emergency decree to legitimate their authority. They started by referencing the severity of the outbreak and the declaration of the emergency decree as a background to whatever measures were being implemented. Some of them were accompanied with provisions of punishments in case of violations, some were not. The orders concluded with the signature of the provincial governor—sometimes as the official overseeing Ubon Ratchathani’s public administration during the emergency or as Chairperson of the Communicable Disease Committee—titles recently concocted to legitimate this undertaking. By repeatedly citing the outbreak as the reason, the state used these orders to create what Louis Althusser calls “interpellation.” The idea was for the public to accept that these orders imposed upon them were “the right thing” to do given the necessity of the situation.

Anti-COVID-19 campaign signs provided by the Ubon Ratchathani City Municipality are placed throughout the province, especially in urban areas.

Second, the orders were written in Thai in the formal register called “official language”. This official language is marked with a degree of ambiguity and abstraction prevalent in Bangkok-centric bureaucratic culture, making them hard for ordinary people to understand. For example, the order dated March 18, 2010 required businesses to close temporarily. On the list was a business called sathan prakopkan khlai sathan borikan สถานประกอบการคล้ายสถานบริการ (Businesses resembling service businesses). It was not clear what the phrase means and why the word khlai คล้าย (to resemble) is used. Also common is a lack of explanation as to why certain measures were used. For instance, the ban on sales of alcoholic drinks was issued with no explanation, as if none were necessary. The official language is a gatekeeping tool—excluding ordinary people from engaging with the discourse in the text while allowing only certain chosen ones to enter into the discourse. The orders were addressed to the heads of government units in the province, who have access to check their understanding of the message in the orders. The general public, despite being the one imposed upon, does not have such access. The way the language is used is best characterized as a one-way communication for the intended audience to follow, not to question or negotiate for a clear understanding. This illustrates the post-election government’s lack of accountability towards its own citizens—a continuity of approach since the 2014 coup.

According to its own website, the Interior Ministry’s first duty is bambat thuk bamrung suk hai kae prachachon บำบัดทุกข์ บำรุงสุข ให้แก่ประชาชน (Get rid of the people’s hardships and maintain their happiness), but unfortunately what we have seen in these difficult times, is that the ministry seems to understand control without accountability as a way of fulfilling that duty. In the grand scheme of things, the flawed 2019 general election has allowed authoritarian rule to continue, and the CO VID-19 outbreak has created a perfect environment for it to thrive. As a result, while the number of infections are reportedly going down, so are the hopes and indeed the morale of ordinary Thais.

Even grocery carts, popular in villages far from fresh markets, are suffering from dramatically reduced sales.

30 April, 2020

References

- Althusser, Louis. 1971. Lenin and philosophy and other essays. New York and London: Monthly Review Press. [Translated version of the 1968 publication by Ben Brewster].

- Mongkol Bangprapa. 1 March 2020. Students vow to ramp up protests in coming weeks. Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/politics/1868569/students-vow-to-ramp-up-protests-in-coming-weeks. (Accessed 1 May, 2020)

- Ubon Ratchathani Province website. 2020. การแก้ไขปัญหาและวิธีป้องกันการระบาดของโรคติดเชื้อไวรัสโคโรน่า จังหวัดอุบลราชธานี (Solutions and preventive measures for the coronavirus outbreak in Ubon Ratchathani Province). http://www.ubonratchathani.go.th/th/index.php?name=menuview&file=readmenuview&id=94. (Accessed 1 May, 2020)

Notes

- The author would like to thank Petra Desatova for her valuable comments on my views.

Saowanee T. Alexander is Assistant Professor of Sociolinguistics at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchathani University.

Citation

Saowanee T. Alexander. 2020. “Discursive Control, Thai-Style: The Ministry of Interior and the COVID-19 Outbreak” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.