Keywords: COVID-19, Mexico, Philippines, Packaged Food, Inclusivity, Poverty

COVID-19, a virus one hundred times smaller than a cell, has pushed millions of people over the edge, and aggravated our dominant economic system. With both Mexico and the Philippines, both geographically distant but united by history, as of the 3 May, authorities reported 22,088 infections and 2,061 deaths in Mexico1 and 9,223 and 607 respectively in the Philippines.2 Media analysts simply report statistics and official discourses on COVID speculative consequences but we should observe and learn from the significant occurrences and constructive responses in two subcontinents of the global south.

We can summarize the way COVID-19 arrived in these two nations by focusing on eight common issues: 1) political disputes over class privileges; 2) deficient health systems, reflected by a lack of hospital beds, ventilators, materials, and a deficit of more than 250,000 doctors; 3) a large proportion of populations living in an informal and subsistence economy; 4) hundreds of thousands of hardworking and talented emigrants struggling to send remittances; 5) governments indebted to international powers; 6) national states co-opted by corporate powers; 7) structural inequality, poverty and marginalization embedded in social relations and culture; and 8) environmental concerns, aggravated by hurricanes, earthquakes, droughts and fires. In interpreting these points, we can notice that there are historical and structural limitations which cannot be covered in this writing, but these should be kept in mind when reading the following sections.

COVID-19 in Mexico: between an epidemic of obesity and drug-cartels

Mexico, a land rich in agricultural produce, is suffering an obesity epidemic. 75% of the population is overweight and a large proportion of people are dealing with high blood pressure and diabetes. Indeed, Mexico is ranked at the top of population with diabetes per 100,000 inhabitants; second in adult obesity and fourth in children obesity (Global Obesity Observatory, 2020). The main reason for this social nightmare can found in the high consumption of ultra-processed, packaged, canned or bottled food (GRAIN, 2015), which in turn is a consequence of the free trade liberalization and other disadvantageous policies for domestic agriculture implemented since 1986 when Mexico entered the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and particularly after Mexico’s entry into the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.

This information is relevant because the regular consumption of corporate packaged food (CPF) causes inflammatory processes that weaken the immune system of human bodies making people more susceptible to infections by viruses, and can be said to have facilitated the rapid expansion of COVID-19. The Deputy Minister of Health, Dr. López-Gatell confirmed the argument: “compared to other regions of the world, we have a greater number of serious cases in young adults; this is the result of the serious, large and longstanding epidemic of obesity, overweight, diabetes, hypertension and other chronic diseases, all associated with more than four decades of poor nutrition…low quality foods with very high caloric value and very low nutritional value” (April 19, 2020 press conference).3

It is no coincidence that Mexico’s main neighbor, the United States of America (U.S.), also plagued by obesity, has also become a pandemic epicenter. Problems in the U.S. notably affect Mexico. One infamous saying states that ‘when the U.S. suffers a cold, Mexico gets pneumonia.’ The multifaceted impacts of COVID-19 on the Mexican people living in the U.S.—around 15 million by birth and more than 30 million by ethnicity—through the cutback of remittances that feed millions of families in Mexican territory is one good example of this.

The COVID-19 impact on Mexico may be greater than it is today because only 16% of the population has daily access to drinking water and most houses (around 60%) are small and precarious.

The lack of water has diminished the power of the ‘wash your hands’ rule. In addition, poor housing and overcrowding in poor neighborhoods has exacerbated domestic violence, in 2019 an average of 10 woman have been assassinated daily (INEGI, 2019), and during 2020 the level of violence against woman continues, furthermore in a state of sanitary contingency.4

Indeed, the application of ‘international standards’ such as quarantine, the disruption of main social and economic activities and so on, without taking into consideration local circumstances might prevent the rapid spread of the virus. Yet, this has escalated other problems such as obesity resulting from the consumption of CPF and a lack of outdoors activities has led to increases in domestic violence, and desperation to obtain money for food, water, and medicines. This last point opens the door for drug cartels to extend their influence into marginalized areas. A recent widely reported case occurred in the marginal areas of Guadalajara where relief packages were distributed by the daughter of el Chapo Guzman, an iconic drug leader now imprisoned in the U.S. The “Chapo relief kits” (see Pictures 1a, and 1b) included rice, beans, sugar, cookies, various types of pasta for soup, mashed potatoes, oil, toilet paper, and a letter signed by Alejandrina Guzman, Capo’s daughter, which says, “Crucial to our brand Chapo 701 is helping all less fortunate Mexicans: our elderly who have taught us a legacy of respect and tradition.” Social networks of the “brand” foresee an extended help as they receive many requests to bring food to vulnerable people.

In fact, in the social network arena, drug cartels seem to compete for people’s sympathy via relief kit donations.5 In their photos and videos, one is able to see boxes with slogans such as ‘from your friends CJNG (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación), a support by contingency COVID-19’ or ‘The Lord of the Cocks, the Mencho with the People’ or ‘Cartel del Golfo support my Matamoros, Mr. 46 Cowboy’ (See Picture 2). In response, peoples’ comments in social media have thanked gangs’ aid, and messages are usually accompanied by the classic greeting of Mexican mothers: God bless you.

COVID-19 in Metro Manila: between severe lockdown and impotence

The Mexican situation might be familiar to those familiar with the Philippines. However, larger problems of infrastructure, public services and malnutrition among the poorest aggravate the situation in the archipelago. Overweight and Obesity are becoming a considerable social threat (FNRI, 2018; Global Obesity Observatory, 2020) and criminality in marginalized areas remains a constant issue. The threat and fear of these, overused by President Rodrigo Duterte and his like-minded politicians are used to implement abusive policies, disrespectful of human rights.

An aggressive form of government has also been seen in the handling of the COVID-19 crisis. Arrests for violating guidelines have happened in the main slums areas of Metro Manila.6 Peoples have been desperate to leave since a lockdown was announced in March 15. The national government and Metro Manila authorities set up checkpoints around and between cities enclosing and prohibiting the movement of around 19 million people. Some locations were extremely locked-in after positive cases of corona virus were reported in the vicinities, and the inherent restriction of social and commercial activities has provoked a debacle for hundreds of families who rely on daily work to feed their families.

For example, in Payatas, Tatalon and Dakota slum, neighborhoods where I maintain social ties derived from my doctoral research fieldwork, most people cannot leave and their inner economic activities have been interrupted. These include carinderias (eateries) and sari-sari stores businesses, garbage collection, junk shops for recycling, construction works, and so on. One of my host informants, Tita Amparo, in Payatas has kept me up-to-date on what is happening. She is 58 years-old, unmarried, without children, and her main occupation is running a street food stall next to the barangay7 administrative office. The lockdown has dramatically affected her, and what is worse, she did not count as a priority for local officials because she does not form part of a “household.” She only lives with one nephew who works for her business. Under this crisis, both are eating rice, once or twice a day with a modest ulam (side dish) of noodles or whatever she can get from others. Her physical and mental health is at risk. The last messages I received on April 25, 2020, from her nephew was

Hello po, I said Tita amparo you need help from you will not money today, because a lot of Covid 19’ and ‘please you give me help from you.

This message is similar to other messages I have received from friends in Payatas, Tatalon and Dakota slums.

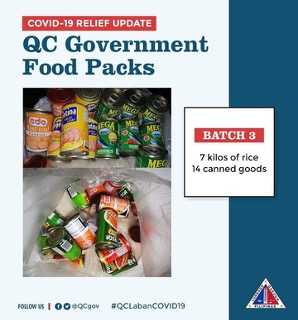

Officially, many families in Metro Manila have received a small package from the local government, which includes 2kg or 3kg of rice and some packaged and canned goods (Pictures 3a, 3b, 4a and 4b). One man with a 24 year-old with wife and three children, wrote to me on April 20, “the barangay gave us rice, latas (cans of sardines) and noodles but it’s only for three days po.” He also asked me to help his parents, his father is a Palero (garbage collector) and her mother is a housewife with occasional informal jobs.

Powerless, I have channeled my worries to my contacts in organizations intervening in slums, but there is also a certain impotence in what they themselves can do. Messages from the director of an NGO that helps Badjau in Dakota clarifies the point:

My contact texted some are going out still and so some are standby along the road hard to think if they catch the virus I don’t know what will happen to the community i feel hopeless no one can come to get the goods and no one can go to bring to them something i feel bad and emotionally sad for these people.’ (9:09 a.m. March, 27)

This message came after describing what relief packs the Badjau people had received (Picture 5a, 5b, 5c and 5d):

it is only for max three days depending on family members numbers it can only be one or two days our government gave packs good for one week and the Lgu 1000 per family i am still working for another distribution one at a time i am very careful not to get that virus but doing my little way, i have to do something quick fir these people so help me God” (09:44 p.m. April 4).

Impotence comes to all of us who have an affinity with the vulnerable.

Knowing the increasing state of emergency, at the end of April, the government announced a Social Amelioration Program for low-income families. These may receive between PHP5,000-8,000 (¥10,500~16,800) but the bureaucratic procedures to be completed by poor people have been questioned. The number of households to be covered, and the mechanisms to provide the aids to those who really need it are also uncertain. And even if the money is successfully given it is highly possible that the consumption of CPF, alcohol, cigarettes and unnecessary products will increase.

Shining light into the darkness

Cash and relief packs of food provided by the government can be considered to be oxygen, but eating rice with CPF increases health risks and incite bodies to consume more. However, human are not passive and frequently respond by shining light into the darkness. Those are interventions that lay the foundation for a more inclusive society. In this sense, I will briefly describe the cases of FFA in Payatas and Piuma in Mexicali.

Fair Play for All, Payatas, Philippines

Fair Play For all Foundation (FFA) is managed by Roy Moore (UK) who since 2011 intervenes in Payatas by teaching football and bringing democratic education to children who have dropped out of school. FFA focuses on reversing childhood trauma while fostering good sleep, good nutrition, good exercise, mental health support, social support and mindfulness. To face COVID-19, FFA postponed sports and educational activities, and set up hand-washing stations and they bought temperature scanners to check for temperature. Additionally, thanks to donations, FFA was able to deliver food packages to 88 families (around 350 people) that included 5kg of rice, 1kg of monggo (lentils), 1kg of string beans and 4kg of assorted vegetables (pumpkin, okra, upo, sweet potato or cabbage (see Pictures 6a and 6b).

FFA also cooked an emergency menu included oatmeal, lentil soup, and bean curry. Children can commute to the Fairplay Cafe with their own bowls for assigned meals and then return home. These fresh, local vegetables and legumes not only are cheaper per meal8 than CFP and canned goods, but also boost the bodies’ immune system. In my opinion, this seeds a constructive landmark in the minds of children about how to fight off future viruses.

Pictures 6a and 6b. Food Packs for Badjau people

PIUMA, Mexicali, Mexico

PIUMA is non-profit organization that was founded in 2016 by students and graduates of the University of Baja California when thousands of Haitian migrants arrived in the city hoping to cross the border into the U.S. For the vast majority, it is not possible to emigrate to the U.S. and they end up staying in Mexico. For various reasons, it is difficult for Haitian people to integrate into Mexican society, thus PIUMA focuses on programs for their inclusion via technical education, giving them the tools for having chances to get a manufacturing job.

COVID-19 has strongly hit to manufacturing border cities such as Mexicali. Since mid-March, the government has set up check points and restricted economic activities, but maquila factories did not close due to capital interests. Local government has provided hygienic equipment and food relief kits, but Haitians (and other migrants) are frequently excluded. For this reason, PIUMA activists immediately took action to print information about COVID-19 in Creole (Picture 7) and to distribute them along with 92 chickens to Haitians. It is important to say that they do this in an area where the temperature frequently exceeds 40 degrees9 .(Pictures 8a, 8b, 8c and 8d)

Additionally, during the month of April, they have organized campaigns to give masks, glasses, and hand sanitizer to approximately 60-70 Haitians selling at the traffic lights. Later, thanks to donations, they were able to set up a campaign to provide 150 relief kits that contain a minimum of ultra-processed food. They have prioritized oats, rice, beans, corn and wheat flour (see Picture 9). They also posted COVID-19 information in the barber shop, restaurant, and church where most of Haitian people congregate and meet. Since the beginning of May, they are cooperating with other organizations to give medical consultations and, if necessary, medicine to pregnant Haitian women who have recently arrived in the city.

The social value of the efforts of PIUMA lies in the coordination of organizations, the involvement of university professors and students, and the inclusion of the Haitian community with the Mexican people. These actions mark the collective conscience of the people, particularly in the memories of young active people who continue to sow the seeds of change beyond borders.

A call for solidarity beyond borders

After COVID-19, things will not ‘go back to normal.’ However, it will be our task to turn the world towarder the brighter rather than darker side of the moon. There will be a need to struggle for more inclusive healthcare systems that can confront upcoming sanitary and environmental crises. Yet, can we really rely on the leadership of governments and international organizations that apply “standards” without noticing the nuances within the Global South? Can we rely on large corporations or organized criminal gangs? Are we going to continue to rely on money dole outs to solve basic problems of food, shelter and health?

One direct possibility is for us to take control, as a coordinated society, in functional networks. For instance, noticing and fostering the links we can see between the modest but bright actions of those performed by FFA and PIUMA during this COVID-19 crisis. There can be advantages if, through this crisis, there is larger planetary awareness of both fragility and resilience on one side, and interconnection and interdependence on the other side. This can be a point of departure to share information and best practices that can increase solidarity between peoples. The subsequent exchange of experiences, will be necessary to strengthen links.

Mexico and the Philippines will continue to emerge as references of survival and solidarity that must be analyzed comparatively so that we can be stronger to face future crises. The comparative analysis of South-to-South links is an imperative. Aid actions from the global north is welcome, but as we have seen in these months, at critical moments powerful leaders leave everyone looking out for their own self. So it is better to first take care of each other and from that, any complimentary aid that adds and doesn’t subtract will be welcome.

7 May, 2020

References

- Agencia EFE. 2020. A nombre de “El Chapo” Guzmán entregan despensas en Guadalajara. El Universal. 17 April. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/seguridad/el-chapo-guzman-entrega-despensas-en-guadalajara. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Agencia EFE. 2020. Entregan despensas con el rostro de ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán por covid-19. Milenio. 17 April. https://www.milenio.com/estados/coronavirus-despensas-imagen-chapo-guzman-covid-19. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Castillo, Gustavo. 2020. Recuperar base social, propósito del narco en reparto de despensas. La Jornada. 30 April . https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/04/30/politica/014n1pol?partner=rss. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Cu, Rea. 2016. Food and beverage businesses may be leading Filipinos to obesity and death. Business Mirror. 18 January. https://businessmirror.com.ph/food-and-beverage-businesses-may-be-leading-filipinos-to-obesity-and-death/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- FNRI. 2018. Expanded National Nutrition Survey. Food Nutrition Research Institute, Muntinglupa, Philippines.

- Galupo, Rey. 2020. Tondo hard lockdown: 125 violators nabbed. Philstar global. 3 May. https://www.msn.com/en-ph/news/national/tondo-hard-lockdown-125-violators-nabbed/ar-BB13xNqE?ocid=spartandhp. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Global Obesity Observatory. 2020. World Obesity Map. World Obesity Federation. London. https://www.worldobesitydata.org. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- GRAIN. 2015. Libre comercio y la epidemia de comida chatarra en México. https://www.grain.org/es/article/entries/5171. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- INEGI. 2019. Estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de la eliminación de la violencia contra la mujer. Noviembre 21. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía. Comunicado de prensa Núm. 592/19. México.

- Infobae, online edition. 2020. Narcos aprovechan coronavirus en México para repartir despensas y pelear territorio. 20 April. https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2020/04/20/narcos-aprovechan-coronavirus-en-mexico-para-repartir-despensas-y-pelear-territorio/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Infobae, online edition. 2020. Incrementaron en 80% las llamadas por violencia de género durante la emergencia por coronavirus. Abril 24. https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2020/04/24/incrementaron-en-80-las-llamadas-por-violencia-de-genero-durante-la-emergencia-por-coronavirus/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- López-Gatell, H. 2020. Informe Diario COVID-19. 19 April. https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/articulos/version-estenografica-conferencia-de-prensa-informe-diario-sobre-coronavirus-covid-19-en-mexico-240565?idiom=es. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Maspaborito. 2019. Obesity: A Growing Health Problem in the Philippines. 6 September. http://maspaborito.com/2019/09/06/obesity-growing-health-problem-philippines/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Ortiz, Alexis. 2020. Estiman aumento de hasta 100% en violencia de género por confinamiento ante coronavirus. El Universal. Abril 9. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/coronavirus-en-mexico-estiman-aumento-de-hasta-100-en-violencia-de-genero. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

- Voces Feministas MX. 2020. Ante contingencia, el machismo no para y los feminicidios continúan en México. 31 March. https://vocesfeministas.mx/contingencia-machismo-no-para-y-los-feminicidios-continuan/. (Accessed 2 May, 2020)

Notes

- 1 The total population in Mexico is about 129 million

- 2 The total population in the Philippines is about 100 million

- 3 https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/articulos/version-estenografica-conferencia-de-prensa-informe-diario-sobre-coronavirus-covid-19-en-mexico-240565?idiom=es

- 4 https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2020/04/24/incrementaron-en-80-las-llamadas-por-violencia-de-genero-durante-la-emergencia-por-coronavirus/

https://vocesfeministas.mx/contingencia-machismo-no-para-y-los-feminicidios-continuan/

https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/coronavirus-en-mexico-estiman-aumento-de-hasta-100-en-violencia-de-genero - 5 https://www.jornada.com.mx/2020/04/30/politica/014n1pol?partner=rss

https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2020/04/20/narcos-aprovechan-coronavirus-en-mexico-para-repartir-despensas-y-pelear-territorio/ - 6 https://www.msn.com/en-ph/news/national/tondo-hard-lockdown-125-violators-nabbed/ar-BB13xNqE?ocid=spartandhp

- 7 Local administrative unit of government.

- 8 P1,000 ($20) provide two weekly food packages of healthy food.

- 9 Mexicali is one of the hottest cities in the world, reaching 49 or 50 degrees Celsius in the summer.

Heriberto Ruiz-Tafoya is an affiliated researcher at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, and a researcher at the Institute of Social Theory and Dynamics (ISTAD) in Hiroshima, Japan. His research focuses on the political economy of corporate packaged food (CFP), the sociology of eating, and slums’ bottom-up politics. He holds a doctoral degree in economics from Kyoto University. He studied BA in Economics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), MSc. in Technology and Innovation Management at Sussex University (Brighton, UK), a Global Master of Business Administration at the Doshisha Business School (Kyoto, Japan). He has been lecturer of courses in the Economics field, currently in charge of the course ‘Global Political Economy’ at the Graduate School of International Relations School, Ritsumeikan University (Kyoto, Japan).

Citation

Heriberto Ruiz-Tafoya. 2020. “Global Problems, Local Pain: Coronavirus in Mexico and the Philippines” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.