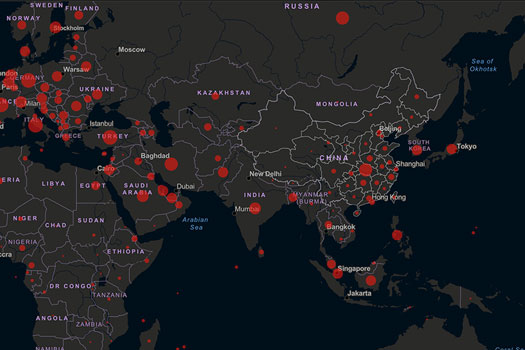

On paper, the situation in Thailand isn’t as severe as many of our Southeast Asian neighbors. As of April 28, the number of patients infected with coronavirus stands just below 3,000, with 54 fatalities. That we have managed to contain the outbreak despite being one of the first countries outside of China to report cases is something the government of Prayut Chan-ocha is never tired of repeating, either through his face-masked soliloquy or through the daily briefings from the Centre of COVID-19 Situation Administration, whose acronym, many have quickly noted, reminds us of the military command center set up during the political crackdown of 2010. The military analogy abounds anyway during our “battle” with the invisible enemy.

Numbers don’t lie, as they say (and as we hope). But rosy statistics and congratulations aside, the feeling on the ground is far from relief. It is as if we were teetering on the edge of something terrible, something that could swallow us whole, and even though we’re not actually falling into it, we are treated to a full view of what’s going on down there: disorganization, poor communication, an inability to deal with a complex 21st century crisis, and a Freudian slip of authoritarian desire. In short, everything that has plagued Thailand since the military government seized power six years ago and which its “democratic” reincarnation has assumed responsibility since last year. From the start, the people hardly felt confident. When the outbreak began, there were fiasco after fiasco about the supply of face masks and the apparent inefficiency of the Commerce Ministry to make sure that everyone that needed to be covered was covered. The decision not to restrict entry of foreigners coming in from at-risk countries, again at that early stage of the pandemic, was hotly questioned and interpreted as a move to please China. Meanwhile Thais travelling back from overseas faced confusing quarantine measures. When the numbers rose to alarm the authorities, the prime minister announced the Emergency Decree, which in effect closed nearly all non-essential businesses, and in early April a 10pm-4am curfew was announced, prompting jokes about the virus’ working hours. Thailand’s longest holiday season, the Songkran Festival in mid-April, was cancelled to prevent people from travelling en masse back to their hometowns – though people had already done so returning to their hometowns earlier when all shops and stores were ordered closed and they had no means of supporting themselves in the capital.

What’s the point of being able to save lives from the unruly pathogen if we can’t save people from hunger

The hardest workers are public health officials, and especially volunteers in the province who have kept vigilance and brought the situation under control. Yet by the second half of April, as the number of new cases began to drop, a dreadful sight started to appear and now it threatens to cancel out all the public health success with its naked display of economic reality: Food lines has begun to form as homeless and unemployed people, as of this writing, queue up to receive meals from charitable donors. What’s the point of being able to save lives from the unruly pathogen if we can’t save people from hunger? The fact that Thailand, where “there’s fish in the water and rice in the fields,” still have hundreds and hundreds lining up every day in the scorching April heat to get a pack of rice is just heartbreaking. It’s just impossible.

At the beginning the authorities seemed to focus on curbing cases rather than to handle the economic consequences that come with it, and when they finally announced a cash-relief program, it felt too little too late. Not to mention the same organizational ineptness – who is eligible, who is not, and why – that set social media on fire almost on a daily basis. On April 27, a woman swallowed rat poison at the gate of the Finance Ministry in a suicidal protest. She survived, and the Ministry said she misunderstood her case and would receive the money.

As of this writhing (April 28, 2020), the government has announced an easing of restrictions to begin on May 4. Details are still sketchy (as usual), but it’s likely that the Emergency Decree and the curfew will remain. This has prompted a suspicion that the Prayut administration wants to control the people, and not the virus, and that the mentality of this government is to deal with any problem, viral or otherwise, with a draconian attitude rather than intelligence, empathy and a well-rounded understanding of the modern world in which physical, cultural, political and economic influences are inseparable from one another.

Sure, Thailand is not doing badly and sure, this virus will go away. That much we are certain. But once we get to the point where we perform the autopsy and survey the wreckage, we’ll realize that COVID-19 is just one of the problems: the bigger challenge is how to survive without leaving anyone behind, how to rise up with genuine strength, and how to see through the world that has already changed while we’re trying to blink the virus away.

28 April, 2020

Kong Rithdee has written about film, culture and politics at the Bangkok Post since 1997, first as a full-time journalist and now as a freelancer. He was also a former Asian Leader Fellow Program (ALFP) Fellow (2010). In another capacity, he has co-directed three feature documentaries on Muslim minorities in Thailand including the Convert (2008) and Gaddafi (2013). He is interested in the politics of moving images at a time when the world is saturated with visual information.

Citation

Kong Rithdee. 2020. “Living in the Time of the Virus: A Note from Thailand” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.