Laos was the last ASEAN member state to confirm the presence of COVID-19 within its borders. The Lao Vice Minister of Health announced in a televised press conference on 24 March 2020 that two Lao nationals had tested positive for the virus, a day after Myanmar reported its first COVID-19 case. Dispensing with international health confidentiality protocols, the Vice Minister provided the names of the two patients, in addition to more standard information.

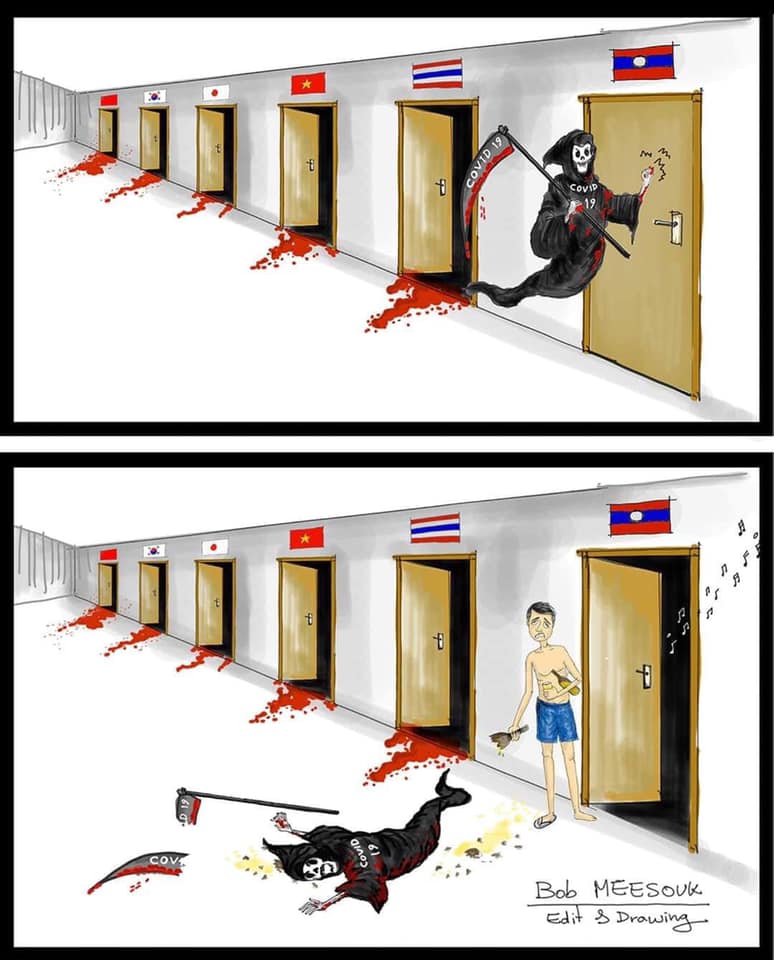

Until the announcement of the positive cases, there appeared to be an element of national pride in Laos’ seeming immunity to COVID-19. Cartoons and stories about Laos’ officially COVID-19-free status circulated online and by word of mouth. Laos was characterized as being superior to other nations affected by the virus: cleaner, less crowded, and ultimately, “stronger,” all of which generated pride. One international manager recounted how, when briefing staff on the pandemic’s progress in mid-March, they burst into spontaneous applause at the mention of Laos’ zero cases. Few seemed to question Laos’ low rate of testing, its narrow testing protocols, and the likelihood of remaining untouched when all surrounding nations had confirmed COVID-19 cases.

A nationalist cartoon highlighting Laos ‘power’ in the face of COVID-19

Lao PDR’s Taskforce on COVID-19 moved quickly following the detection of the first positive cases. It conducted daily press briefings which were televised live, and updated a dedicated government website with transcripts of each briefing, as well as other relevant official announcements. The briefings and website are an impressive – and successful – effort to share information with Lao society on a level I have never before witnessed in more than 20 years in Laos.

Laos was locked-in before it was locked-down. International airlines reduced (and then canceled) their flights to Laos in late March, and transit options for travelers from Laos closed off one by one (Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Bangkok). Ironically, China – where the virus originated – was one of the last countries to close transit options. Non-essential international staff (diplomats, aid workers, teachers) and tourists flew out on the reducing flights, and the Taskforce recommended that Lao nationals overseas delay their return home if possible. Neighboring countries closed their land borders with Laos, culminating in late March in the closure of all Lao border checkpoints. Truck drivers and diplomats remain able to cross, but everyone else was locked-in, not allowed to enter Thailand even for medical emergencies – a common practice for many middle-class Lao nationals and most foreign residents. But the Lao and Thai governments also showed pragmatism, opening the border to allow more than 100,000 Lao laborers to return from now-closed Thai factories. Workers were screened at the border, and monitored in over 2,000 makeshift quarantine centers throughout Laos for 14 days before rejoining their families. Official reports indicate that a small number of the returning workers had COVID-19-like symptoms, but none of those tested were found to be positive.

Laos introduced lock-down measures gradually: kindergartens closed on 17 March, followed days later by all educational institutions, and then a Prime Ministerial Order required most workplaces to close on 30 March until 19 April. Government offices – except for essential services – closed from 01 April. Inter-provincial bus and air travel was suspended, as was Vientiane’s modest public bus service. Lock-down measures for all sectors were later extended until 03 May 2020.

A Vientiane fashion shop promotes its formalwear with matching facemasks (photo courtesy of BT Sewing Wholesale Retail Facebook page)

Impressively, Vientiane’s compliance with the lock-down appears to be high, despite it coinciding with the traditional Lao New Year (Pi Mai) celebration, a loud, highly social and often boozy week of workplace, household and street parties. Authorities banned the sale of alcohol, including beer, for the week of 13-20 April, and again compliance appears to have been high. The streets were unusually quiet: no loud music, no parties, no water fights.

Some districts interpreted the travel restrictions more strictly than others. One urban district of Vientiane installed checkpoints, another announced charges for travel passes. The charges were scrapped within 24 hours, but a number of villages and districts proceeded to issue travel passes for travel outside one’s village of residence. I obtained a pass at my local village office – mainly as a souvenir – which allows me to go shopping at the market for essential supplies. So far, I have not been required to show it at any checkpoints.

As of 30 April, Laos has 19 positive COVID-19 cases, including one foreign national, and no deaths. Eight patients have recovered and been released from hospital with media fanfare. No new cases have been detected since 11 April 2020. Some continue to question the low number of cases, including Thailand, which has added Laos to a list of nations where it considers the virus to be “escalating.” The low numbers can be partly explained by the low rate of testing: 1,927 tests as at 29 April. However, if higher than usual numbers of people were dying at home or in the hospitals, we could expect to hear about it on the grapevine … and we are not.

The way forward is unclear. Authorities have indicated an easing of the lock-down from 04 May, and a phased re-opening of schools from 18 May to 2 June. It is unlikely that much work or study has been accomplished during the lockdown period, as many Lao households are not equipped for working or studying from home. The tourism industry, which accounted for 12.5% of the Lao economy in 2019 according to the World Travel and Tourism Council, has been hit hard by the border closures. The effects on other sectors of the economy are yet to be highlighted. However, Laos’ receipt of foreign aid – an important component of its health and education budgets – is likely to reduce, as donor nations use their tax revenue to fund domestic socio-economic rescue packages, rather than international development cooperation. Will Laos choose to tackle domestic corruption in a bid to become more financially self-sufficient, or will it rely more heavily on neighboring China and Vietnam in this time of crisis?

30 April, 2020

Kathryn Sweet is a social development/policy advisor and independent scholar based in Vientiane, Lao PDR. She has a PhD in Lao history from the National University of Singapore. She has published on the history of medicine and development issues in Laos.

Citation

Kathryn Sweet. 2020. “Locked-in, Locked-down: COVID-19 in Laos” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.