In August 2020, 64.9% of Indonesia’s regions are expected to reach the peak of the dry season (BMKG, 2020). It’s onset also signals the beginning of the fire season which in the past has resulted in transboundary haze, an air pollution event that causes respiratory illnesses and severely impacts public health and socioeconomic activities in the region. Concomitantly, at present Indonesia is experiencing a surge in COVID-19 infections, with an average of 841.28 cases a day since 2 March, 2020 and is currently the worst-hit country in Southeast Asia (BNPB 2020).

To mitigate fire risks in the dry season and manage fires during this pandemic, the Indonesian President Joko Widodo held a limited Cabinet meeting on 23 June in the Merdeka Palace, calling for consolidation and coordination of surveillance and law enforcement activities among national and local stakeholders. Rasio Ridho Sani, the Director General of Law Enforcement of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) argued that forest and land fires (karhutla) were rooted in people’s ignorance, opportunistic behavior and moral hazards and therefore, should be approached through education, law enforcement, monitoring and surveillance. Furthermore, he added that fire-fighting during the pandemic faces two main challenges: a high risk of contracting COVID-19 due to a reduced immune system as a result of the haze and maintaining COVID-19 protocols during fire mitigation and fire-fighting missions (Sani, 2020).

In this article we focus on understanding the influence of COVID-19 and fire mitigation, contextualize forest and land fires in Indonesia, and describe how mitigation is being affected by COVID-19. We clarify that the former shows a relationship between fires and political-economic motives. It has been predicted that the additional pressure from COVID-19 will decrease rural non-farm household income by 24% and that of rural farm households by 17% during the ongoing social distancing period (Pradesha et al. 2020). As a result, the cost-saving measures of using fire for land clearance may increase. The following sections present the complexity of forest and land fires in Indonesia and how the adjustment of fire mitigation practices due to COVID-19 may present nothing more than a temporary solution.

Forest and Land Fires in Indonesia

Indonesia frequently experiences multiple forest and land fires, resulting in extensively burnt areas (Gaveau et al., 2014; Purnomo et al., 2017). These are predominantly triggered by human activities and exacerbated by land degradation as well as climatic conditions such as low rainfall due to the El Niño and Indian Ocean Dipole (Field, Van Der Werf, & Shen, 2009). The causes, actors and motives behind forest and land fires varies. Tomich et al. (1998) have identified three including land clearances, accidental fires and fire as a weapon of social conflict. Applegate et al. (2001) have also added resource extraction such as fishing or deer hunting as another human use of fire.

Fire for land clearing is widely considered the cheapest and easiest solution for small farmers, many of whom are unable to afford machinery or pesticides (Carmenta, Parry, Blackburn, Vermeylen, & Barlow, 2011). This traditional slash-and-burn practice was -and continues to be- blamed as a cause for forest and land fires. However, environmental organizations have also highlighted the role of logging, pulpwood and oil palm concession owners as being responsible for forest and land fires (Suyanto & Ruchiat, 1998). The impact of these concession owners causing fires is more significant in peatlands due to their activities in building drainage canals for plantations (Hooijer et al., 2012). Peatlands compose of partially dead organic matter in a waterlogged environment, store vast amounts of carbon and release more carbon emissions when burned (Jaenicke, Wösten, Budiman, & Siegert, 2010). Drained peatlands lead to low water tables and increase the risk of fire (Taufik et al., 2017). Fire can also be utilized as a form of land expansion and acquisition. Suyanto (2007) showed how fires were used both by companies and communities to expand their territory in Lampung and Jambi. In Riau, Purnomo et al. (2017; 2019) have illustrated how fire increased land price by up to 28% and how this benefited multiple actors, especially local elites and farmer group members, such as village heads and land speculators.

To prevent forest and land fires, the Indonesian government implemented a law on zero burning (Law No.32/2009) on environmental protection and management. This sanctions any person caught burning to three to ten years of imprisonment and a fine of three to ten billion IDR (US$ 203,000~676,000) (Article 108). The same Law Article 69 point 2, however, states that any burning prohibition should also include local wisdom, which permits burning up to two hectares per head in each family. A more operational regulation for forest fires was Government Regulation No. 4/2001 on damage or pollution related to forest and land fires. This addresses the coordination of firefighting activities among government officials from the national level to the sub-district level. However, this regulation has been ineffective due to unclear institutional responsibilities between the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Forestry, which at that time were still separated (Nurhidayah, 2013). Additionally, compliance to these regulations by actors is low as shown by Saharjo & Yungan (2018) in Riau. Despite mandates that concession owners should have fire prevention facilities, human resources and a proper fire mitigation system, many locally-owned oil palm and forestry companies did not comply to this regulation and contributed to forest fires in 2013-14.

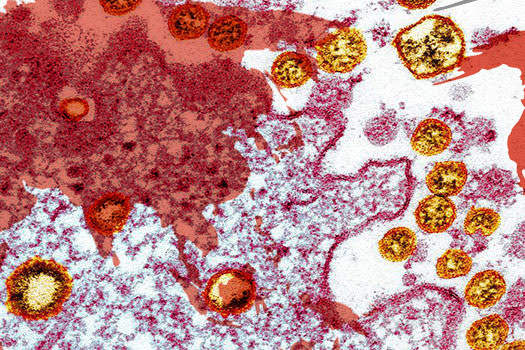

These fires and haze led to the death of 19 people and more than half a million acute respiratory infections in 2015 (Purnomo et al. 2017). A recurrence of haze during Indonesia’s dry season could place many communities at high risk to COVID-19, especially those who have suffered from past respiratory infections.

Local farmer tried to extinguish fire over peatlands with a simple pump. The picture was taken on September 2019 in Jambi. Source: Y.A. Fatimah.

COVID-19 and Fire Mitigation

On 6 February 2020, the Indonesian President held a fire coordination meeting, which was attended by the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, the Minister of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), Commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, Chief of the National Police and Head of the National Disaster Mitigation Agency. Their institutions through Forest Fire Control Brigade (Manggala Agni) (under MoEF), military at village level (Babinsa), police at the village level(Bhabinkamtibnasi), Regional Disaster Mitigation Agency, and Community of Fire Care (Masyarakat Peduli Api) are in charge of fire mitigation at the village level. This meeting was followed by declaring six provinces and two districts as being under a state of emergency for fire with Riau province having the longest period of 264 being under this until October 2020.

In the coordination meeting held on 23 June, 2020, President Jokowi said, “In the midst of COVID-19, we have a big task to anticipate forest and land fires” (Setkab 2020). During the meeting, he emphasized good coordination and monitoring for fire prevention, the importance of controlling fires before they become too big, law enforcement for burning activities, and consistent peatland management. Despite special attention given to fire mitigation during the dry season, MoEF reduced its total budget from 9.32 trillion IDR (US$ 629.25 million) to 7.74 trillion IDR (US$ 522.48 million) (or 16.95%) for COVID-19 responses as mandated by the President Instruction No. 4/2020 on accelerating COVID-19 responses and President Regulation No. 54/2020 on change in the 2020 state revenue and budget allocation (MoEF 2020). To accommodate COVID-19, the MoEF allocated 1.01 trillion IDR (or 13% from their total budget) for social assistance to communities in and around forest areas affected by COVID-19 (MoEF 2020). The budget reallocation for COVID-19 responses and the overall budget cut led to a decrease in fire mitigation integrated patrols budget by 34% (Ungku & Christina, 2020).

Ruandha Agung Sugardiman, the Director General of Climate Change at MoEF, said that COVID-19 adds these following challenges towards Indonesia’s fires: some fire-prone areas are under large-scale social restrictions and this limits fire mitigation activities; responsibilities for Babinsa and Bhabinkamtibnas are split between fire management and COVID-19 prevention; a decline in people’s economic welfare could lead to a potential increase in fires; fire fighters risk being exposed to COVID-19; and the budget reallocation has affected the fire mitigation budget (6 August, 2020). To reduce the risk of COVID-19, Manggala Agni adjusted their activities by adopting 1.5-2 meter physical distancing in trainings, reducing number of people per patrol car by half as well as practicing personal hygiene and promoting COVID-19 work protocols.

Similar challenges have been faced by companies managing fires in their concessions. Anselmus Supriyanto from Sinar Mas Agro Resource and Technology (SMART) said that community engagement, coordination and capacity building are being conducted virtually. Training, which was previously done across units, is currently conducted independently per unit (pers. comm, 28 June, 2020). To reduce the possibility of fire fighters and workers who live in the concession contracting COVID-19, SMART conducts daily temperature screening, and does not allow workers to leave the concession unless for urgent matters. No external guests (especially from areas with a high number of COVID-19 cases) are allowed and the company does not hold large meetings. Moving towards virtual communication has also been adopted by Musim Mas via WhatsApp chat groups within communities. Banners that remind communities about fire risks are put up in villages and sub-district offices. Safe distancing measures also limit Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper (RAPP) activities in their Fire Prevention program. Craig Tribolet from RAPP mentioned that their crews have been restricted from their engagement with farmers and other community members (pers. comm, 27 June 2020). Likewise, one of our co-authors, Saad, A., a Peat Restoration Agency expert, has noted that the local police of Jambi have installed CCTVs to monitor haze during the pandemic to reduce the number of people that need to go to the field. Since July, however, fire mitigation activities have been increased in Jambi by improving coordination between the military, police, companies, Regional Disaster Mitigation Agency, and Community of Fire Care. The number of fire posts and implementing daily patrols have also increased.

Fire coordination between the military, police, company, and the local community in Jambi. Source: A. Saad.

What may be premature to predict is the economic impact of COVID-19 on fires. The World Food Programme (WFP) reported that one million workers in Indonesia have been told to work from home with reduced or no income, and furthermore more than 350,000 formal workers were laid off (World Food Programme, 2020). This unemployment may encourage urban daily workers who lost their job to return to their hometown in rural areas. Pressure on rural areas, especially towards forests has already been on the rise in partnered villages of Community Conservation Indonesia (KKI Warsi) through an increase in the number of cases of illegal logging during the pandemic (Priyanto, 2020). Budi S. Wardhana, the Deputy of Planning and Cooperation, Peat Restoration Agency described the relationship between COVID-19 and fire, as a COVID-haze cycle where social distancing and economic restrictions compel people to go to forest/peatland areas, adding pressure to fire fighters whose mobility is limited due to social distancing and lack of funding. The latter will increase the risk of peat fires that leads to respiratory conditions and an increased susceptibility to severe illness from COVID-19 (August 14, 2020). In response to this condition, the Peat Restoration Agency introduced a program called the “Coronavirus Relief for Indonesian Sustainable Peatlands” with a focus on promoting social distancing and no-burning activities, capacity building in early haze detection, and developing economic activities through home gardens as well as providing capital to the village cooperative in preserving staple food produced on peatlands.

Epilogue

Fighting fires during the COVID-19 will be challenging in the face of a reduction in MoEF spending for fire mitigation integrated patrols, the split responsibilities of Babinsa and Bhabinkamtibnas between fire mitigation and COVID-19 prevention, a shift to virtual training and community engagement, and economic restrictions which add risks to land degradation. While prioritizing COVID-19 protocols is possible during the absence of fire, its presence will make social distancing impossible for fire fighters and create higher risks of severe illness due to haze and COVID-19. These circumstances suggest that fire mitigation during COVID-19 will be more crucial than ever.

2 September, 2020

References

- Applegate, G. B. A., Chokkalingam, U., & Suyanto, S. 2001. The underlying causes and impacts of fires in South-east Asia. Final Report. CIFOR, ICRAF, USAID, USFS, Bogor.

- Article 69 point 2 Law No.32/2009 on Environment Protection and Management (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No. 32 Tahun 2009 tentang Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup). 2009. https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/fulltext/2009/32TAHUN2009UU.HTM (Accessed 1 September, 2020)

- Article 108 Law No.32/2009 on Environment Protection and Management (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No. 32 Tahun 2009 tentang Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup). 2009. https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/fulltext/2009/32TAHUN2009UU.HTM (Accessed 1 September, 2020)

- BMKG. 2020. Prakiraan Musim Kemarau 2020 Di Indonesia (Dry Season 2020 Predictions). 145. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- BNPB. 2020. Indonesia COVID-19 Hub Site. 2020. https://bnpb-inacovid19.hub.arcgis.com/. (Accesed 18 August, 2020)

- Carmenta, R., Parry, L., Blackburn, A., Vermeylen, S., & Barlow, J. 2011. Understanding Human-fire interactions in tropical forest regions: A case for interdisciplinary research across the Natural and Social Sciences. Ecology and Society 16(1):53 https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03950-160153

- Field, R. D., Van Der Werf, G. R., & Shen, S. S. P. 2009. Human amplification of drought-induced biomass burning in Indonesia since 1960. Nature Geoscience 2(3):185–188. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo443

- Gaveau, D. L. A., Salim, M. A., Hergoualc’h, K., Locatelli, B., Sloan, S., Wooster, M., Sheil, D. 2014. Major atmospheric emissions from peat fires in Southeast Asia during non-drought years: Evidence from the 2013 Sumatran fires. Scientific Reports 4:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06112

- Hooijer, A., Page, S., Jauhiainen, J., Lee, W. A., Lu, X. X., Idris, A., & Anshari, G. 2012. Subsidence and carbon loss in drained tropical peatlands. Biogeosciences 9(3):1053–1071. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-1053-2012

- Jaenicke, J., Wösten, H., Budiman, A., & Siegert, F. 2010. Planning hydrological restoration of peatlands in Indonesia to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 15(3): 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-010-9214-5

- MoEF. 2020. KLHK Alokasikan Rp 1,01 Triliun untuk Bantu Masyarakat dan Petani Hutan Terdampak Corona (MoEF allocated 1.01 Trillion IDR (US$ 68.44 million) to help corona affected communities and farmers).http://ppid.menlhk.go.id/siaran_pers/browse/2418 (Accessed 10 August, 2020)

- Nurhidayah, L. 2013. Legislation, regulations, and policies in Indonesia relevant to addressing land/forest fires and transboundary haze pollution: A critical evaluation. Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law. 16(1): 215–239.

- Peraturan Pemerintah No. 4 Tahun 2001 Tentang Pengendalian Kerusakan Dan Atau Pencemaran Lingkungan Hidup Yang Berkaitan Dengan Kebakaran Hutan Dan Atau Lahan (Government Regulation No. 4/2001 on damage or pollution related to forest and land fires). 2001. http://sipongi.menlhk.go.id/cms/images/files/1041.pdf (Accessed 1 September, 2020)

- Pradesha, Angga, Syarifah Amaliah, Anang Noegroho, and James Thurlow. 2020. “The Cost of COVID-19 on the Indonesian Economy,” no. June: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133745

- Priyanto, W. 2020. New Normal untuk Lingkungan Hidup (New Normal for the Environment) – KKI WARSI. https://warsi.or.id/new-normal-untuk-lingkungan-hidup/ (Accessed 3 August, 2020)

- Purnomo, H., Shantiko, B., Sitorus, S., Gunawan, H., Achdiawan, R., Kartodihardjo, H., & Dewayani, A. A. 2017. Fire economy and actor network of forest and land fires in Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics. 78:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.01.001

- Saharjo, B. H., & Yungan, A. 2018. Forest and Land Fires in Riau Province: A Case Study in Fire Prevention Policy Implementation with Local Concession Holders. In Land-Atmospheric Research Applications in South and Southeast Asia (pp. 143–169). Springer.

- Sani, R. R. 2020. Ahli, Teknologi, Strategi, & Penegakan Hukum Karhutla di Tengah Pandemi COVID-19 (Expert, technology, strategy and law enforcement for forest and land fire in the midst of pandemic). Presented at Forest and Land Fire Law Enforcement Webinar, 8 June, 2020.

- Setkab. 2020. Rapat Terbatas Mengenai Antisipasi Kebakaran Hutan Dan Lahan, 23 Juni 2020, Di Istana Merdeka, Provinsi DKI Jakarta (Limited meeting on forest and land fire mitigation, 23 June 2020 at the Merdeka Palace, DKI Jakarta Province). 2020. https://setkab.go.id/rapat-terbatas-mengenai-antisipasi-kebakaran-hutan-dan-lahan-23-juni-2020-di-istana-merdeka-provinsi-dki-jakarta/. (Accessed 16 August, 2020)

- Suyanto, S. 2007. Underlying cause of fire: Different form of land tenure conflicts in Sumatra. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 12(1): 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-006-9039-4

- Suyanto, S., & Ruchiat, Y. 1998. Impacts of Human Activities and Land Tenure Conflict on Fires and Land Use Change: Cases Study of Menggala-Lampung-Sumatra.

- Taufik, M., Torfs, P. J. J. F., Uijlenhoet, R., Jones, P. D., Murdiyarso, D., & Van Lanen, H. A. J. 2017. Amplification of wildfire area burnt by hydrological drought in the humid tropics. Nature Climate Change. 7(6):428–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3280

- Tomich, T. P., Fagi, A. M., De Foresta, H., Michon, G., Murdiyarso, D., Stolle, F., & Van Noordwijk, M. 1998. Indonesia’s fires: smoke as a problem, smoke as a symptom. Agroforestry Today 10: 4–7.

- Law No.32/2009 on Environment Protection and Management(Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia No. 32 Tahun 2009 tentang Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup). 2009. https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/fulltext/2009/32TAHUN2009UU.HTM (Accessed 1 September, 2020)

- Ungku, F., & Christina, B. 2020. Coronavirus cuts force Indonesia to scale back forest protection. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-environment/coronavirus-cuts-force-indonesia-to-scale-back-forest-protection-idUSKBN23W1GD (Accessed 27 July, 2020)

- World Food Programme. 2020. COVID-19: Economic and Food Security Implications.

Yuti Ariani Fatimah is a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at Asian School of the Environment, Nanyang Technological University. Her current research focuses on the role of community participation in peatland restoration in Indonesia, particularly on the human and ecology relationship and knowledge production.

Asmadi Saad is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Agroecotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Jambi, Indonesia. His current research focuses on peatlands, wetlands, groundwater, hydrological modelling, vegetation, hydraulic conductivity, and water quality monitoring.

Janice Ser Huay Lee is an Assistant Professor at the Asian School of the Environment, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She works on rural land systems and investigates the effect of land use and land cover change on biodiversity conservation and human livelihoods. Her research interests include Southeast Asia’s oil palm industry, food security in rural-urban systems, and peatland restoration in Indonesia.

Citation

Yuti Ariani Fatimah, Asmadi Saad and Janice Ser Huay Lee. 2020. “Fighting Fires in the Time of COVID-19” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.