México is a country that presents many migration dynamics due to its proximity to the United States (US); it is not only a source of migrants, but also a country of transit, destiny and repatriation. This last one has been exponentially increasing over the last 10 years with the deportation of not only Mexicans, but also migrants from Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Salvador to México. Until 2019, 40% of deported Central American migrants were from Guatemala (94,306), increasing 26.96% since 2017 (67,343). The only country that reported a decrease in deportations was Salvador, which reported 342 deportations less in 2018 compared to 2017 (26,811-26479) (Agencia EFE 2019).

During the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto in México (2012-18) and that of Barack Obama in the US (2009-17), both countries configured a migration policy based upon mass deportation and México became the most important intermediate country to return migrants to their countries of origin, after being expelled from the US territory. As part of the political harmonization of migration policies of both countries the program “Southern Border” was created, in which a border securitization policy was strengthened, along with large detentions of migrants, deportations and the increase of migration agents in México’s southern border. The goal was to prevent migrants reaching the Mexican northern border.

In 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidency. When taking office, he gave a speech in favor of the protection and defense of the human rights of migrants, including both Mexicans in the US and non-Mexicans in México, with special emphasis on Central American migrants. He also highlighted the importance of Mexican sovereignty in the formulation of migration policies, assuring that Mexico wouldn’t do the “dirty work” of the US regarding migration. This manifested itself with the arrival of the first migrant caravan in October 2018, where the Mexican government offered humanitarian visas to migrants, and in January 2019 the government implemented an “Emerging program of humanitarian visitor identifications,” which ended at the end of the same month. This initiative was followed by other efforts to grant humanitarian identifications to Central American migrants in Mexico in a swifter manner. It is recognized that even though the “Emerging Program” had a short time-span, it showed the humanitarian focus at the outset of López Obrador’s government regarding migration. Between December 2018 and April 2019, the INM (National Migration Agency) granted a total of 26,584 humanitarian visas. This constituted a 7,000% increase over the previous year; between December 2017 and April 2018, the INM only granted 5,102 humanitarian visas (Leutert, 2020:28).

However, this trend radically changed in mid-2019, when an agreement was negotiated between the Mexican Foreign Secretary; Marcelo Ebrard Casaubón and the US government, where the Centro American migrants that wanted to seek asylum in the US would remain in México, while their asylum request was processed in the US government. In this program named “Remain in Mexico” the Mexican government carried out the migrant protection protocols (MPP). Despite the fact that in this protocol it was stated that the migrants would have the right to work and live legally in Mexico, until today they remain in conditions of vulnerability, due to facing difficulties in obtaining formal jobs and basic services. Added to the migrants that are in the country under this protocol, there is a common influx of migrants that everyday seek to cross into the US. Moreover, the Mexican government has deployed the National Guard, especially along the southern border, to limit the entrance and transit of migrants from Central America.

The role of state governments (federal entities) has also been very limited since migration is an issue managed and regulated by the federation, those resources that are used to care for and manage these flows are determined and redirected by the federal government towards the state and municipalities without taking into account the real needs or intensity of the phenomenon, which generates a limited capacity for local government to act toward it. The federal government, on its part, also built two shelters and integration centers for migrants where the attention of the MPPs was needed, with limited results in both Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez.

Historically, in Mexico, civil society has been the sector that has had more incidences in México regarding issues of migration, especially NGOs that operate migrant shelters, where they secure shelter, food, clothes, medical attention, and other services.

Once migrants enter national territory at the time where they are attended to in the administrative process of the National Institute of Migration, shelters are the first reference that returning migrants obtain concerning a safe place where they can sleep, eat, clean themselves and receive a change of clothes. According to the IOM, in Baja California there exist around 23 shelters operated by NGOs, whose responsibility has remained being attentive to migratory flows.

In this context, it is very important to speak of the situation that these shelters, managed by Baja Californian civil society, have faced since the arrival of COVID-19 in the state, in particular for two important events. The first, a complex scenario that organizations face due to the suspension of government funds, which meant that their sustainability depends entirely on donations from society and foundations. The second is the positioning of Baja California as the national epicenter of the pandemic.

The Arrival of COVID-19 in Baja California and the situation of migrant shelters

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 as a global pandemic and six days afterwards, there two confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Mexicali, Baja California, the most northwestern state in Mexico that shares the border with California, USA. On 18 March the first death was registered in Mexico and there were 495 confirmed accumulated cases nationwide, as of 27 April, there are more than 23,500 confirmed accumulated cases and unfortunately 2,807 deaths. On 17 May, Mexico City, the State of Mexico, Tabasco, Veracruz and Baja California had 51% of active cases (Ricardo & Tula 2020). On 22 June, around 140 thousand people recovered their health after suffering from COVID-19, being at that time the fatality rate in Mexico of 12.2% (Lara & Tula, 2020). By 8 July, Mexico reached 282,248 confirmed accumulated cases, 33,512 accumulated deaths, an estimate of 29,129 active cases and about 172,230 recovered cases, the main comorbidities, according to the confirmed cases for this last date are; hypertension with 19.97%, obesity 193.31%, diabetes 16.28% and smoking with 7.55% data obtained on the portal of the Government of Mexico (2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the federal government to take different measures. One of those was that Estaban Moctezuma Barragán head of Public Education Secretary in Mexico announced a school break from 20 March 2020, however due to the fast increase of the cases of COVID-19 around the country, General Health Council whose President is Dr. Jorge Carlos Alcocer Varela, declared a national emergency, cancelling all non-essential activities in the public, private and social sectors until 30 April. To that date there were 28,496 confirmed cases and 3,484 deaths nationally; in Baja California were 2,292 confirmed cases and 388 deaths according to the Mexican government (2020). However, we should note that the numbers that the daily reports that the federal government shared didn’t match the numbers of the COVID-19 site of the Mexican government.

In Mexicali, the capital of Baja California, since the first 15 days of the pandemic, the contagion has shown a similar trend as that in Wuhan, China, according to Alonso Pérez Rico, de health secretary of Baja California (INFOBAE 2020). Therefore, the Government of the State of Baja California (2020), began to take preventive measures such as suspending educational activities, closing beaches, shopping malls where there are supermarkets, night establishments, bars, cinemas, and gyms; to not go to crowded places, not attend meetings; emphasis was placed on essential border crossing, the suspension of activities that encourage movement in different sectors; and in the case of restaurants, services were limited to take-out food only. In addition, a call was made for employers to abide by sanitary measures, otherwise they would be subject to a fine, as stated by the Baja California Ministry of Labor and Social Security, whose titular is Sergio Moctezuma Martínez López.

However, despite the continuous efforts of Baja California’s government, COVID cases have continued to increase, due to transit and movement inside the city and across the international border; the constant crossings across the borders of San Diego-Tijuana and Mexicali-Calexico of not only people whose work is in one or another city of the United States and live on the Mexican side, but also for non-essential activities such as social and family gatherings, shopping and tourism that relaxed social distancing mainly in the cities of Mexicali and Tijuana. In the latter, towards the second week of April hospitals became saturated, with health personnel with COVID and with a lack of sufficient protective equipment according to Mckee & Del Monte (2020). Over the following weeks the cases kept increasing making Baja California one of the three states with the most COVID cases, and it wasn’t until 23 June when it dropped to 6th position nationally in terms of cases (Luna, 2020). However, six days later, Baja California is still considered to be one of the states with a higher incidence, with 240.86 cases per 100,000 people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the population, especially migrants that are in the main cities of Baja California, which are border cities with the US. The consequences for migrants have been exacerbated due to a lack of attention from the authorities and institutions that are supposed to provide them support (Moreno & Olvera 2020), limiting mobility inside the country due to the partial closure of some states and of the US border. On the other hand, health services for non-COVID diseases and other conditions have been limited, also affecting the migrant population, such as attending to births. Moreover, administrative processes for migrants have slowed down and on 23 March the office of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (COMAR) suspended activities, freezing all processes. Since 17 March, the US government has taken advantage of the pandemic to declare express deportations, which are carried in the first hours that migrants arrive to the US (Moreno & Olvera 2020).

These situations have meant that Mexicali and Tijuana have become a “waiting room” for all migrants that have pending migration processes, since asylum requests are considered non-essential by the US government, according to Moreno & Olvera (2020). In the case of migrants under the MPP, their appointments in US courts have been deferred to resume as of 16 July (Beltran, 2020). The pandemic has also affected migrants coming from Mexico’s southern border that wish to request asylum in the US, due to the suspension of the processes (Moreno & Olvera, 2020).

All these situations directly affect the shelters along the border. Different sources have shown that the shelters of Mexicali, Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez are around 70% full. In Mexicali, most of the shelters aren’t receiving any income and only some of them have received support, via the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Shelters like “Posada del Migrante” and “Casa de Ayuda Alfa y Omega” have received some migrants, but in “Posada del Migrante” migrants are not allowed to go out. With the latter going out is restricted to work reasons, since several migrants don’t have the resources to cover the cost required by the shelters. The “Hijo pródigo” shelter is the only one in Mexicali that is receiving migrants, for which they have installed tents donated by the IOM, as a pre-filter to detect COVID-19 cases, however the measures are not taken thoroughly.

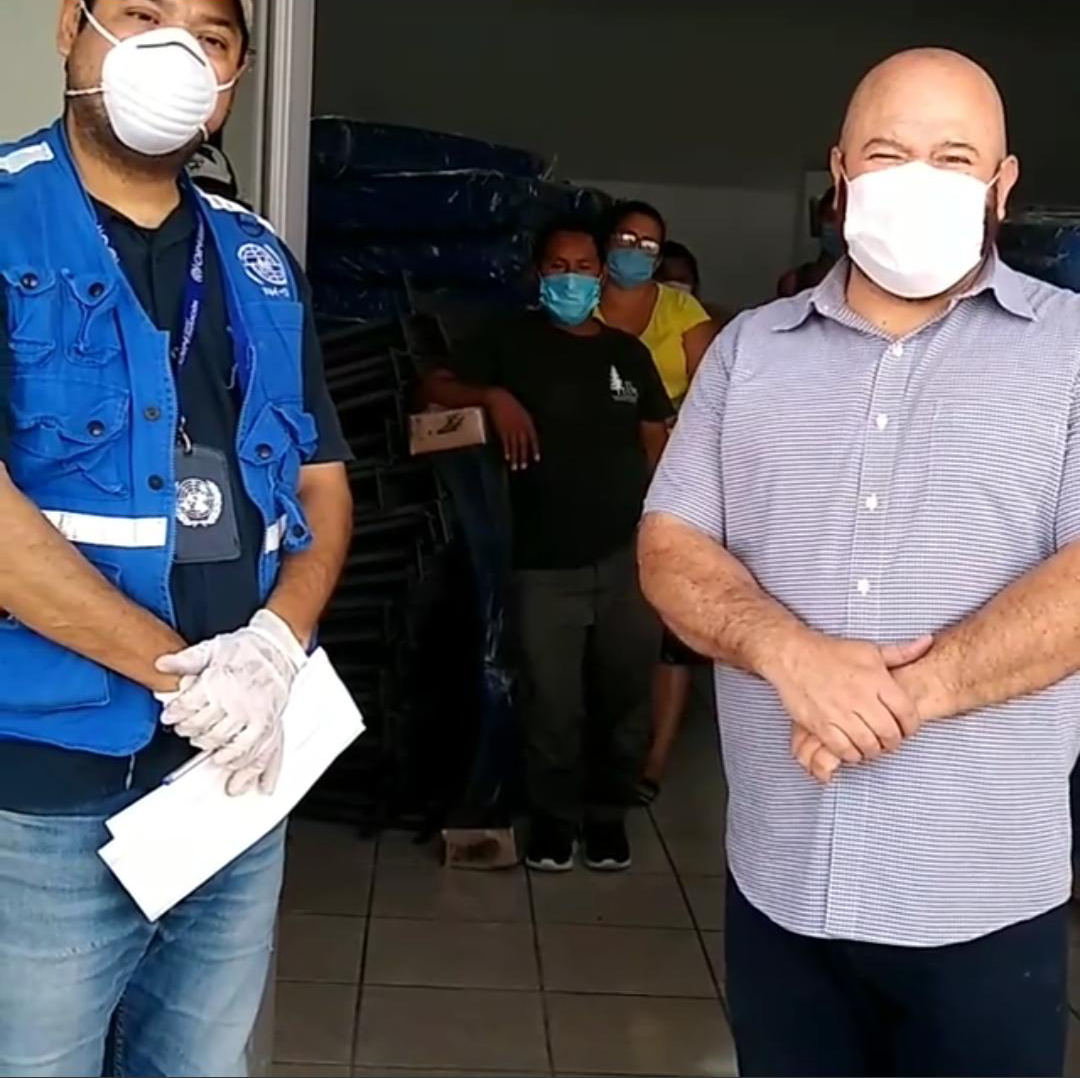

Most of the supplies to deal with the pandemic in migrant shelters operated by civil associations come from donations from international agencies and people. Source: “Casa de Ayuda Alfa y Omega” migrant shelter (2020).

In the absence of government resources, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has provided supplies to shelters to deal with the pandemic: these are for cleaning, food and laboratory tests. Source: “Casa de Ayuda Alfa y Omega” migrant shelter (2020).

Sadly, the authorities have forsaken migrants, and the only support planned is to distribute some basic products, but nothing concrete. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the IOM have supported migrants with health and hygienic products, as well as providing tents. IOM plans to install a pre-filter lodge for migrants, and once they have passed an observation period they will be directed to the shelters.

There have been positive COVID cases in the migrant population in shelters, even affecting staff. Health personnel that have been giving medical assistance in the shelters stopped doing so. The authorities haven’t sent food or defined epidemiological protocols for this population. It is worth noting that when migrants have turned up in hospitals they haven’t been received, but IOM has played an important role to negotiate with private hospitals to let migrants have medical attention.

Some migrant shelters provide food once or twice a day, these are donated by people or foundations. Source: Migrant shelter Cobina A.C (2020)

Provisioned food is donated by society or foundations, some which are free and others at cost and these are prepared by the same migrants in the facilities of the shelters. Source: Migrant shelter Cobina A.C (2020)

Under the current public health crisis caused by COVID-19, the mental health of migrants is important, because they face a despairing scenario, of uncertainty and precariousness, dealing with stress, anxiety and situations of depression; these ailments are exacerbated in migrants that aren’t in shelters or that lost their jobs. Since an important portion of migrants work in informal jobs, several of them lost their income sources, and the migrants that lost formal jobs also lost access to medical attention. COVID-19 has shown and exacerbated the problems of Mexico with the migrant population, also affecting people who assist them: the uncertainty remains constant.

1 July, 2020

References

- Agencia EFE. 2019. EE.UU. y México deportan 196,061 centroamericanos en 2018, 37,9% más que en 2017(US and Mexico deport 1960,061 Central Americans en 2018, 37.9% more than 2017). https://www.efe.com/efe/america/sociedad/ee-uu-y-mexico-deportan-196-061-centroamericanos-en-2018-37-9-mas-que-2017/20000013-3885917 (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Casa de Ayuda Alfa y Omega Albergue para Inmigrantes. 2020. Les presento la importante ayuda en esta pandemia hecha por la organización OIM a el albergue y aprovechó para solicitar de tu ayuda el migrante (I present the important help in this pandemic made by the IOM organization to the shelter and took the opportunity to request the migrant for your help). https://www.facebook.com/Casadeayudaalfayomega(Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Cobina A.C. 2020. Tenemos 96 niñas y niños en nuestro albergue Cobina la Posada del Migrante un albergue familias (We have 96 girls and boys in our hostel Cobina la Posada del Migrante, a family hostel). https://www.facebook.com/Cobina-AC-706714219387987 (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Gobierno de México. 2020. Covid-19 México. Información General (General Information) https://coronavirus.gob.mx/datos/#DOView (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Gobierno del Estado de Baja California. 2020. TIJUANA, BC a 30 de marzo de 2020. En Baja California se intensifican las medidas preventivas para evitar que la curva de casos por COVID- 19 se eleve. (Tijuana, Bajacalifornia 30 March 2020. In Baja California, preventive measures have intensified to prevent a curve of COVID-19 cases from rising). http://www.bajacalifornia.gob.mx/noticia_gobbc.html?NoticiaId=616 (Accessed 10 Jul, 2020)

- INFOBAE. 5 April, 2020. Alerta en Mexicali ante el coronavirus: la ciudad más afectada de Baja California tiene una curva “idéntica” a la de Wuhan. (Alert in Mexicali to the coronavirus: the most affected city in Baja California has an “identical” curve to that of Wuhan). Mexico News. https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2020/04/05/la-curva-epidemica-de-mexicali-es-practicamente-identica-a-la-de-wuhan-secretario-de-salud-de-baja-california (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Lara, R., & Tula, M. 2020. Mapa del coronavirus en México; 75 por ciento de contagiados se ha recuperado (Map of the coronavirus in Mexico; 75 percent of infected have recovered). https://www.milenio.com/estados/coronavirus-casos-mexico-mapa-22-junio (Accesed10 Jul, 2020)

- Leutert, S. 2020. Las políticas migratorias de Andrés Manuel López Obrador en México (Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s immigration policies in Mexico) (p. 28) Strauss center for international security and law, University of Texas: EUA.

- Luna, D. 23 June, 2020. Mexicali está en una meseta de contagios por Covid-19: Alonso Pérez Rico. (Mexicali is on a plateau of infections by Covid-19: Alonso Pérez Rico). Cobertura 360. https://cobertura360.mx/2020/06/23/baja-california/mexicali-esta-en-una-meseta-de-contagios-por-covid-19-alonso-perez-rico/ (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Mckee, R., & Del Monte, J. 2020. COVID-19 y la vulnerabilidad de las personas migrantes en Tijuana: una crisis inminente (COVID-19 and the vulnerability of migrants in Tijuana: an impending crisis),p. 23. https://observatoriocolef.org/boletin/covid-19-y-la-vulnerabilidad-de-las-personas-migrantes-en-tijuana-una-crisis-inminente/ (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Moreno, J., & Olvera, P. 2020. Poblaciones migrantes y refugiadas en el contexto de la pandemia COVID-19. (Migrant and refugee populations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic). https://www.facebook.com/elcolef/videos/999039333832512 (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

- Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. 2018. Directorio de casas y albergues para personas migrantes (Directory of houses and shelters for migrants) p.7-30. https://kmhub.iom.int/sites/default/files/directorio_de_casas_y_albergues_para_personas_migrantes_digital_0.pdf (Accessed 30 June, 2020)

Interviews

- Beltrán, H. (2020). Personal interview.

- Mexicali, B.C: Ramirez, Kenia. Diosdado, T. (2020). Personal interview. Mexicali, B.C: Ramirez, Kenia

Kenia María Ramírez Meda is a researcher and professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC), Faculty of Social and Political Sciences. She has a PhD in Transpacific Relations from the University of Colima, and a Bachelor of International Relations from UABC. She also carried out post graduate studies on economics and labour markets at the University of Castilla la Mancha, Spain. For civil organizations she has collaborated with migrants of Haitian origin for the creation and foundation of a Civil Association: the Haitian Movement in Mexicali, Baja California. In addition, she has participated in the round tables for migrant assistance for the Baja California State Government to coordinate strategies and actions for the arrival of the migrant caravan of central Americans.

Adriana Teresa Moreno-Gutiérrez is currently a full-time master of public administration student from the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. She has a master of science in education and a bachelor of administration from the Universidad del Valle de México. Her research interests include migration, vulnerability, and public policies.

Citation

Kenia María Ramírez Meda and Adriana Teresa Moreno-Gutiérrez. 2020. “Migrant Shelters under COVID-19: An Approach from Baja California, Mexico” CSEAS NEWSLETTER, 78: TBC.